Warsaw Reconstruction Route

-

About the route

The Things of Warsaw are authentic witnesses and participants of Warsaw’s reconstruction. Discover testimony about the destruction and history of the rebuilt city by walking along the Warsaw Reconstruction Route.

Be on the lookout for orange stickers with the name of the route in the following rooms:

The Warsaw Data, History of Old Town Houses (level -1),

Room of Warsaw Monuments, Room of Warsaw Mermaids, Room of Souvenirs, Room of Postcards, Room of Architectural Details, Rooms of Plans and Maps of Warsaw (level 0),

Room of Photographs, Room of Warsaw Views, Room of Architectural Drawings (level 1),

Room of Clothing, Room of Portraits, Room of Medals (level 2),

Room of Relics, Room of Warsaw Packaging (level 3),

and the Observation Point (level 5).

We cordially invite you to visit our branch, the Heritage Interpretation Centre – Museum of the Reconstruction of Warsaw’s Old Town.

Curated by Dr. Jarosław Trybuś.

Production and translation by Joanna James.

-

Introduction

Warsaw’s post-war reconstruction was one of the city’s most significant events in the it’s 20th century history. This year we are celebrating the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, which, for Warsaw, meant the beginning of its reconstruction. The post-war reconstruction required a massive effort and was decisive in creating the city’s present appearance. The issue of the city’s reconstruction has been questioned and its effect has been criticized. This is understandable – the devastated city was rebuilt almost entirely, and the decades-long project took place in everchanging and unfavorable circumstances.

Not every plan or objective was completed, but the most important goal was achieved. The ruined capital was rebuilt and became a living, developing and attractive place for its residents. The main motivation for thousands of people involved in the rebuilding process was the memory of their beloved, now non-existent city and faith in a better tomorrow.

-

1. History of the city

The Warsaw Data, level -1

phot. Museum of Warsaw

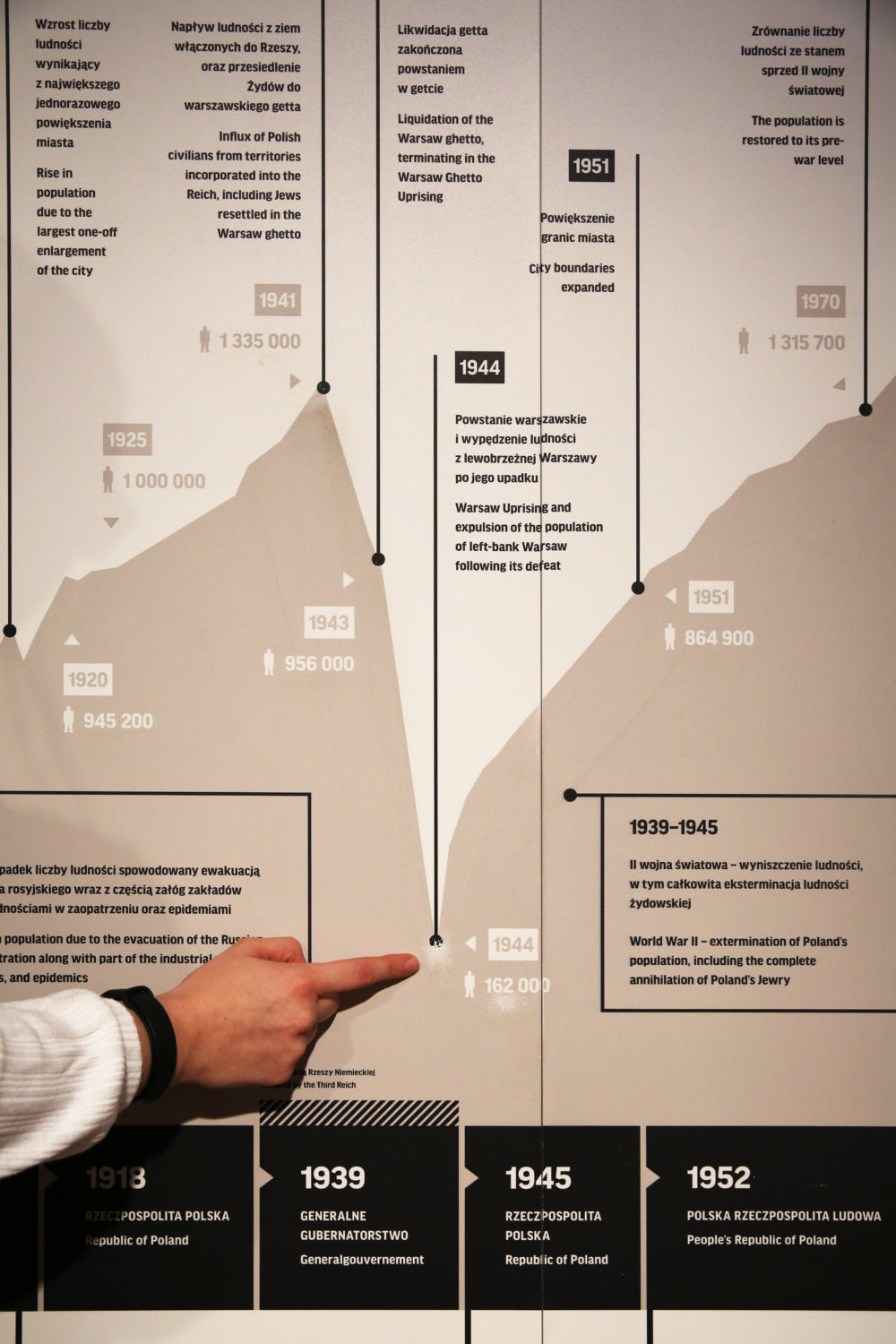

About the dramatic decline of the city’s population and about the time needed to redevelop it.

This timeline shows the most important events in Warsaw’s history and changes in the city’s area and population. One spot has nearly been wiped away by visitors’ fingers: the city’s population in 1944.

This point is one of the pieces of data that helps convey the scale of Warsaw’s destruction. It represents the death, escape and displacement of thousands of inhabitants in the 1943 and 1944 Uprisings. In 1943, the ghetto was liquidated and razed to the ground after the Uprising. With about 450,000 inhabitants, the Warsaw Ghetto was the largest ever organized. The final and greatest blow was inflicted on the city during the 1944 Uprising and the city’s systematic destruction after its fall. Before 1939 more than one million people lived in Warsaw. It took twenty-five years, until the 1970’s, for the population to return to these levels.

-

2. Spatial changes

The Warsaw Data, level -1

phot. Museum of Warsaw

About the most densely built European city and its transformation based on the “Athens Charter”.

In these simplified plans, buildings are represented with the dark colour and everything else (roads, green areas, squares) are represented by the lighter colour. They show the density of buildings in the central part of the city at various times in its history.

The diagram, “The Age of Industry”, shows Warsaw just before its destruction. The colour black dominates, because the city was built-up extremely densely. The diagram, “The Modernist City”, presents Warsaw in the second half of the 19th century, when it experienced a demographic explosion. The development of its industry resulted in mass migration to the city. Warsaw could not expand, being surrounded by a collection of Russian forts. People at that time instead built higher and more densely to use the available space as efficiently as possible. On the eve of the War, Warsaw was the most densely populated city in Europe.

In 1945, when the city was in ruins, urban planners and architects had the opportunity to rebuild it, correcting the mistakes and shortcomings of the pre-war capital. Blocks of flats surrounded by greenery and low service buildings were raised in the city’s central districts . The courtyards of the Old Town were enlarged, a significant part of the Vistula Escarpment was cleared of buildings, old streets were widened, and new ones were marked out. Historic parks were also expanded.

Everything was done in accordance with the provisions of the “Athens Charter”, a document prepared by progressive architects and urban planners led by Le Corbusier. The charter contained a diagnosis of the deficiencies of old cities and a number of prescriptions for their improvement. The charter was also a set of instructions for the construction of new cities which would guarantee a good life for its residents. Work on its final version lasted a decade, from 1933 to 1943. The knowledge and recommendations contained in the “Charter” were important guidelines for the reconstruction of many European cities after World War II.

Post-war Warsaw is one of the greenest and least dense cities in Europe. Today, there are 20,000 hectares of green areas, and the building and population densities are one-third what they were before the war.

-

3. History of Old Town Houses

History of Old Town Houses, level -1

phot. Muzeum Warszawy

About the reconstruction of the Museum’s tenement houses.

Three models of the museum’s tenement houses show their condition before destruction (1938), after destruction (1945) and after reconstruction (1953). An estimated 70 to 80 percent of buildings in Warsaw were lost during World War II.

Conservatory and preparatory work for the future reconstruction of the Old Town began immediately after Warsaw’s liberation in January 1945. An inventory of debris of the Old Town began in March.

The northern facade of the Market Square, now entirely occupied by the Museum of Warsaw, was left in the best condition. Tenement houses nos. 34 and 36 were one of the few that did not burn down completely or collapse during the 1944 Uprising. Both survived thanks to concrete-reinforced ceilings installed in 1939. The Szlichtyngowska tenement house (no. 34) burnt out, but its facade, including its portal and bars survived. Inside, the brick vaults and even the wooden ceilings survived. They can still be seen in the Room of Photographs and in and in the Room of Clothing.

The tenement house Pod Murzynkiem (no. 36) survived in even better condition. The roof truss with the skylight made it through, as well as the walls, wooden and concrete-reinforced ceilings, the staircase, and even window joinery. The house’s facade with its portal, iron grille, door and a (slightly bruised) sculpture also survived. Thanks to the concrete-reinforced structure, three original wooden ceilings with polychromes from the 17th and 18th centuries were not damaged. Unfortunately the buildings located on other sides of the Market Square were in much worse condition.

-

4. Chariot – fragment of the frieze of the Grand Theatre

Room of Architectural Details, level 0

Chariot – fragment of the frieze of the Grand Theatre

Paweł Maliński

Warsaw

1830-1833

stucco

MHW 15656About what is left of the destruction; about reconstructing a “better” version; about a well-used opportunity.

Opened in 1833, Warsaw’s defining building, the Grand Theater, operated for 106 years. Designed by Italian architect, Antonio Corazzi, for years it embodied the metropolitan position that Warsaw aspired to.

The building was hit during the Luftwaffe bombings in September 1939. Filled with flammable materials, it caught fire and burned.

The remains of the theatre suffered again during the Uprising in 1944. Until the city’s liberation in 1945, only the eastern part of the facade with the column portico survived and it’s structure was secured by preservationists just after the war. During that time the remains of the original cornice decorating the facade were removed. Like many more valuable remains excavated from the ruins, they found their way to the collection of the Museum of Warsaw.

A scene from Sophocles’ ancient tragedy is depicted on the cornice. The creator of the decoration was an excellent sculptor, Professor Paweł Maliński from the Department of Fine Arts of the Royal University. Maliński made the frieze out of stucco, however, during the reconstruction of the Theater, it was decided that the original would be replaced with a more durable, stone replica. Therefore, the surviving fragments of the original sculpture were able to remain in the Museum, being a testimony to its author’s craftsmanship and a witness of the dramatic destruction.

The destroyed theater was relatively small. During the reconstruction, the building’s interior was expanded and the number of seats grew from 1200 to almost 2000. The new stage is one of the largest opera stages in the world.

The new theater has also been equipped with the latest technical solutions. The creator of this complex project was Bohdan Pniewski. His design was chosen in a competition in 1951. Work on the new Grand Theater began in 1953. Reconstruction, or rather construction, aroused considerable controversy. The reason was not only that it required enormous costs and a spectacular effort in times of great scarcity, but also its association with bourgeois entertainment. Moreover, construction quickly began to drag and due to the technical complexity of the project, it was difficult to find contractors. Eventually, the new Grand Theater, hidden behind the old facade, opened twenty years after the war – in 1965.

-

5. Miniature of the King Sigismund III Vasa Column

Room of Warsaw Monuments, level 0

Miniature of the King Sigismund III Vasa Column

Bronze and engraving workshop of Władysław Miecznik

Warsaw, c. 1950

bronze, cast

MHW 1/MAbout the reconstruction of the Column, about the exhibition “Warsaw Accuses”, about urban adjustments.

Sigismund’s column, the oldest secular monument in Warsaw and Poland, the symbol of the city, was hit by a tank shell on the night of 1-2 September 1944 during the Uprising. The structure collapsed, but the statue of the king survived the fall of 20 meters in relatively good condition.

Immediately after the liberation, it was taken to Warsaw’s National Museum and shown at the famous exhibition, “Warsaw Accuses”, which focused on the destruction of the capital. It was organised by the Warsaw Reconstruction Office and was presented in many European cities.

The reconstruction of the column was financed by public fundraising and completed at the same time as the East-West Route. The new core was made of gray granite from the Polish city of Strzegom; the statue and bottom of the base were repaired; and the monument was moved 6 meters to the north-east towards Krakowskie Przedmieście. This shift improved the view of the Square from the south but was also done to complement the lowering of Royal Castle Square’s elevation, which was meant to improve its proportional relationship to the nearby buildings.

The restoration and replacement of the missing parts of the statue as well as the reconstruction of missing tablets were done by the Warsaw bronze workshop of the Łopieński Brothers. The reconstruction project was managed by Stanisław Żaryn. Plans to set up the column and technical supervision over the entire process were carried out by prof. Stanisław Hempel. The reconstruction of the column and the very complicated process of its erection were followed closely by the public and the press.

The column was officially unveiled on the opening day of the East-West Route, 22 July 1949. This miniature was made around 1950 in the studio of Władysław Miecznik. It, and others like it, were used as official government gifts.

-

6. Poster with a mermaid

Room of Warsaw Mermaids, level 0

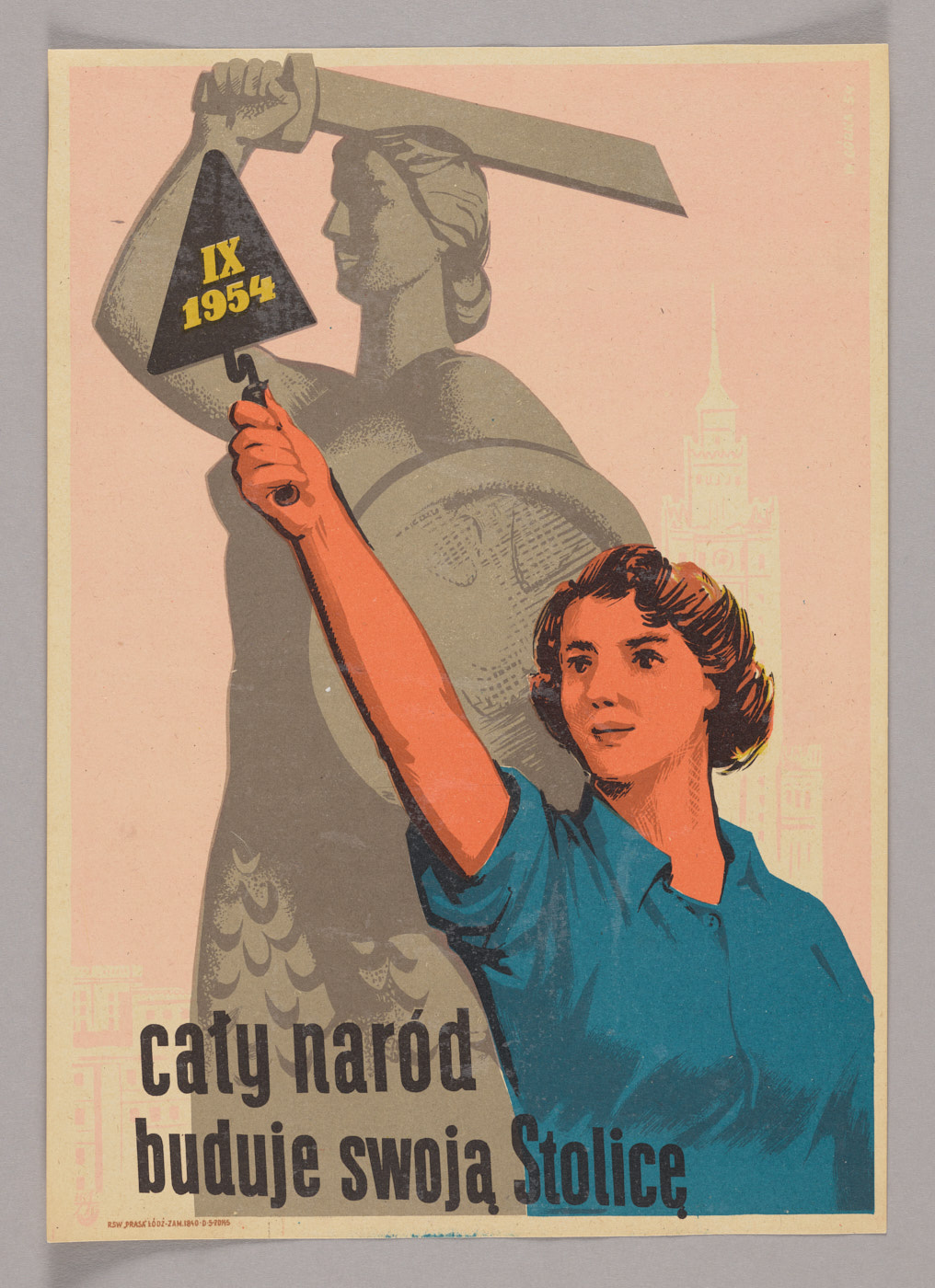

Poster with a mermaid “The whole nation is building its capital!”

Wiktor Górka

1954

paper, print

MW 1112/PAbout reconstruction propaganda and the catchy slogan created by Bierut.

The reconstruction effort was accompanied by state propaganda. Images of young, smiling men and women working for the common good decorated posters, press and newsreels.

A poster must be clear and straightforward. It is intended for short viewing and has to achieve a persuasive goal – that’s why posters encouraging reconstruction or informing about its different stages were based on quick associations.

This poster with the inscription “The whole nation is building its capital!” shows a young, strong woman with an expression of satisfaction on her face and a trowel in her raised hand. Behind her we see Mermaid by sculptor, Ludwika Nitschowa. The mermaid needed a sword and shield but a modern, post-war person of peace builds – they do not destroy, hence the trowel with the date ‘September 1954’ in the woman’s raised hand. The date refers to the reconstruction which was celebrated annually in September. Presented in the background are the largest investments of the rebuilt capital: the Palace of Culture and Science and the outline of high downtown blocks, perhaps the Marszałkowska Residential District (PL: MDM). The suggestive slogan, “the whole nation is building its capital!”, is attributed to Bolesław Bierut.

-

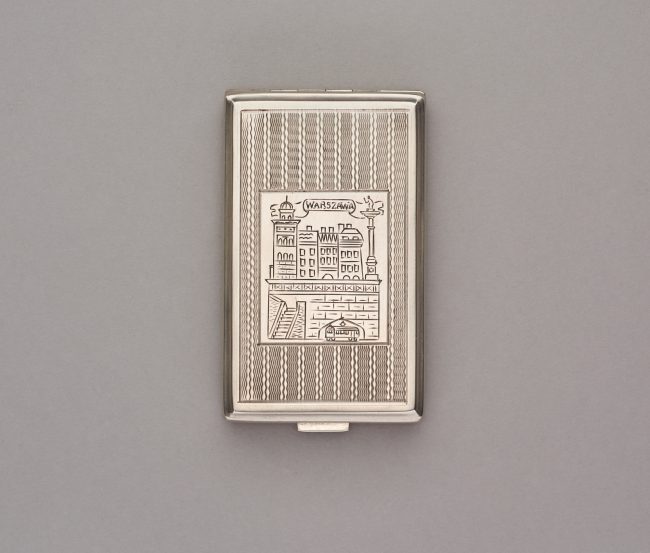

7. Cigarette case with a view of the East-West route

Room of Souvenirs, level 0

Cigarette case with a view of the East-West route

Centrala Przemysłu Ludowego i Artystycznego Cepelia

Warsaw; 1950s.

silver cut, guilloche, engraved

MHW 29335About the East-West route and its role as a symbol of modernization.

The post-war reconstruction was an opportunity to fix some of the shortcomings which affected the city before the war. One of the problems was the lack of a convenient east-west connection.

A second route next to Aleje Jerozolimskie had been planned since the beginning of 20th century. Unfortunately none of the plans for it were executed. The city couldn’t afford it. Joining the eastern part of the city with the western only became possible after liberation.

On 20 March 1947, under the pressure of spring ice floes, a temporary, wooden bridge collapsed at the end of Karowa Street. Poniatowski Bridge, which was reconstructed only nine months earlier (22 July 1946), became the only crossing in the city. This situation forced the decision to build a new route connecting the East and West as soon as possible. The project was called the W-Z Route and to organize it, a special department of the Warsaw Reconstruction Office was established. The department prepared a plan of a route connecting the rebuilt bridge with the city. The new street would be made in a tunnel under Krakowskie Przedmieście using the opencast method. The scale of damage to the buildings standing above enabled this decision. The buildings were demolished and then restored.

The project was a huge undertaking. Besides the almost 7 kilometer-long (6760m) route, during the same period from late autumn 1947 to 22 July 1949, 53 buildings were built or rebuilt. Among them were the Copper-Roof Palace, palaces and tenement houses in Krakowskie Przedmieście, Miodowa Street, Bielańska Street, Leszno Street and Bankowy Square. As part of the W-Z Route project, the first post-war housing estate was built to replace the former, chaotic architecture of Mariensztat. The scale of its architecture was supposed to resemble a small town.

This new route whose tunnel crossed the former center became a symbol of the modernity of post-war Warsaw and evolved into one of the most significant images of the city.

-

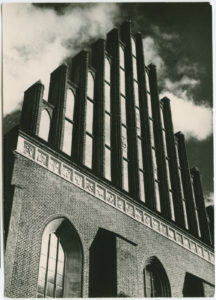

8. St. John’s Archcathedral

Room of Postcards, level 0

St. John’s Archcathedral

phot. Teodor Hermańczyk, Polskie Towarzystwo Turystyczno-Krajoznawcze

Warsaw, 1960s

AI 6627

Katedra św. Jana Chrzciciela

wyd. Antoni Chlebowski i S-ka

Warszawa, po 1905

AI 1807About changing the church’s style before and after the war.

The cathedral was rebuilt in 1947. For this case, it was decided not to restore the building to its pre-war form, but to return it to a medieval style it had centuries before. However, this design would not be a faithful reproduction of its previous form either.

Unavailable plans and inventories of the medieval cathedral were replaced by a reconstruction based on scientific deduction from representations in graphics and paintings and the building’s own remains. The new form of the church facade was heatedly discussed.

Some argued for the reconstruction of the alleged appearance of the fifteenth century facade with a tower, others for the facade from the time of the Vasa Dynasty. There were also voices for the reconstruction of its state immediately before the war, a facade in the English neo-Gothic style. Ultimately responsible for the reconstruction of the cathedral, Jan Zachwatowicz proposed a form invoking the Mazovian Gothic style while at the same time so restraining its decoration that it could be considered a contemporary work. The new gothic cathedral was ready in 1952.

-

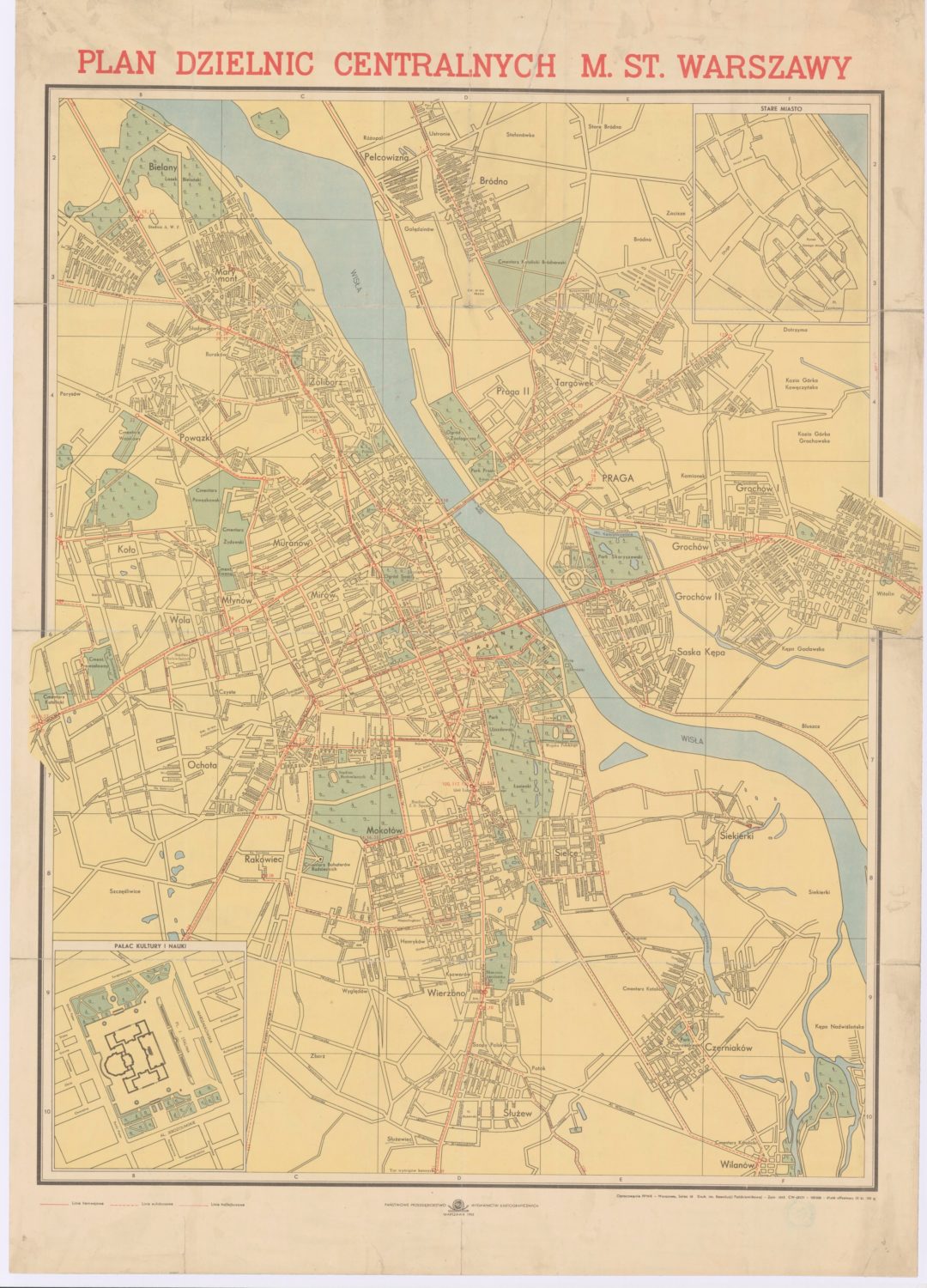

9. Plan of the Central Districts of Warsaw

Room of Plans and Maps of Warsaw, level 0

Plan of the Central Districts of Warsaw 1:21 000

Państwowe Przedsiębiorstwo Wydawnictw Kartograficznych

1955

MHW 95/PlAbout urban changes; about the Warsaw Reconstruction Office.

This plan shows urban changes in the recovering city. Clearly visible are: the new East-West route (PL: Trasa W-Z) and the Śląsko-Dąbrowski bridge.

A new point on the city map is the Palace of Culture and Science (formerly the Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science), which was laid across an already existing street grid. Just south, Konstytucji Square was built on a widened Marszałkowska Street, surrounded by buildings in the social realism style. 10th-Anniversary Stadium was built on ramparts made of rubble on the east side of the Vistula.

The square in the upper right hand corner of the plan shows the rebuilt Old Town – a new, and at the same time old, tourist attraction.

The Warsaw Reconstruction Office, established on 14 February 1945 and responsible for all activities related to the reconstruction, created the rules governing the reconstruction of the Old Town. Among its accomplishments were: preserving the historical street network, loosening the space between buildings, improving transportation by creating pedestrian routes, and introducing green areas in blocks’ courtyards and the areas of former fortifications.

Due to its undeniable flaws, it was decided not to reconstruct the exact architecture and medieval urban planning of its pre-war state. The Old Town was transformed with a surrounding neighbourhood into a historic district with a new, residential function.

Architects decided to improve housing conditions and demolish or not rebuild the outbuildings and other annexes erected later next to the tenements. Instead, green areas replaced them in the free spaces of the courtyards. This met the modernist demands for access to light and air contained in the Athens Charter.

The Old Town was planned to become not only a residential area but also one of the city’s cultural centers. The reconstruction plan of the Old Town shows references to pre-war concepts for improving the utility of this district.

-

10. Construction of MDM (Marszałkowska Residential District)

Room of Photographs, level 1

Construction of MDM (Marszałkowska Residential District), finishing work on a group of sculptures decorating a building

Edward Hartwig

c. 1952, print 2017

photographic print

AN 102/HAbout social realism.

Marszałkowska Residential District is the flagship investment of the second stage of reconstruction. The style has changed and the implementation of the projects has gained political significance.

In 1949, social realism was decreed the obligatory artistic doctrine. This was an unprecedented event in the history of Polish art. Here, the state officially recognised that it accepted only one style — it had to be socialist in content and national in form. For the MDM, its content was the inhabitants. The blocks were built for the working class. The form of the district was inspired by ancient architecture, hence the cornices, stone cladding and rich architectural detail.

The district, which consists of buildings around Plac Konstytucji, a fragment of Marszałkowska Street, and Zbawiciela Square was built in only two years, from 1950-1952.

Alfred Funkiewicz

MDM- Marszałkowska Residential District, Konstytucji Square

22 April 1954, Warsaw

photography

AN 2126/F -

11. Reconstruction of the Royal Castle

Room of Warsaw Views, level 1

Reconstruction of the Royal Castle

Wacław Palessa

1974

oil on canvas

MHW 19089About the last stage of the reconstruction; about traditionalists and supporters of modernization.

The Castle was the last symbolically important building destroyed during the war to be rebuilt. The history of this site’s reconstruction is long and complicated. Not only the form of the Castle was argued, but also its function. There were ideas for it to hold the Museum of Polish Culture or the seat of the highest state authorities.

The final decision on the future shape of the Castle was only made 26 years after the war, in 1971. It was finalized by the first secretary of the PUWP Central Committee, Edward Gierek. Despite announcing an October 1978 headline in Trybuna Ludu that, “there is again a Castle in Warsaw”, work continued on the Castle interiors and were not completed until 1984. After that, the Castle was officially opened to the public.

The Royal Castle is a special example of conservation. It was inspired by the maxim “conservare est novam vitam dare” – conservation gives new life. Currently, the Castle contains relics of a medieval building, but it is rebuilt as an early Baroque residence. Furthermore, one could more precisely describe it as a city palace, with balanced proportions and architectural accents associated with a city. Its front, however, faces the river, where there was once a busy road and is where the residence was supposed to look the best.

In 1980, the Royal Castle and the Old Town were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. It was considered an extremely successful and faithful reconstruction, a model for other conservations in the world.

-

12. View of Saski Palace from Krakowskie Przedmieście

Room of Warsaw Views, level 1

View of Saski Palace from Krakowskie Przedmieście

Zieliński Stanisław

Warsaw, 1936-1938

oil on canvas

MHW 274About the only permanently-preserved ruin in Warsaw.

Since the war, the now non-existent Saski Palace has only been a name. Before it was destroyed it was a complex of apartments, which after 1918 was controlled by the General Staff of the Polish Army. Two massive buildings were connected by a very impressive columnade. This original layout was designed in the 1930s by architect Adam Idźkowski. Today, from the entire original structure, there only exists part of the arcades which houses the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Now and then there are discussions about rebuilding Saski Palace. Some people cannot stand this important building being absent from Warsaw’s landscape. It is worth remembering that leaving a void in place of the centrally-located building was a conscious decision by our ancestors, a memory of the city from before the destruction.

The people rebuilding Warsaw chose these three arcades of the ruined colonnade to be a symbol of destruction and a warning for future generations. The triumphal arch contrasts with the green wall of the restored Saski Garden and has become a witness of destruction and a new symbol of the city.

-

13. Stalls in the archcathedral of St. John the Baptist

Room of Architectural Drawings, level 1

Stalls in the archcathedral of St. John the Baptist

Maria Zachwatowicz

1967

pencil, tracing-paper

scale 1 : 1

MHW 7140/PlAbout the reconstruction of the stalls commissioned by King Jan III Sobieski.

Among the many architectural drawings related to reconstruction in our Museum collection, this set may be particularly surprising.

These drawings were intended for craftsmen reconstructing cathedral stalls and they were made with great precision and attention. Richly decorated benches for the clergy burned down during the 1944 Uprising. It was decided that their style in the rebuilt cathedral would not change. The decision to reconstruct them was probably influenced by their patron. The stalls were commissioned by Jan III Sobieski as a votive offering for the victory in the Battle of Vienna (1683). They were decorated with emblems and statues of saints.

The drawings were made by Maria Zachwatowicz (1902-1994), an architect conservator, and author of many designs of reconstructed buildings. The reconstruction of the stalls was carried out in 1963-1973.

-

14. Polychromed ceilings

Room of Clothing, level 2

phot. Museum of Warsaw

About reinforced concrete ceilings; about Hempl and his method.

In 1936 the city council bought three tenement houses in the Old Town Square for the Museum of Old Warsaw. At that time, the buildings were not, structurally, in good condition. It was necessary to strengthen their structure to enable them to support the collection and its visitors.

Work began in 1938 and the person responsible for it was engineer Stanisław Hempel (1892-1954). In the museum’s tenements he used a method which strengthened the structure while still allowing its historic ceilings to be preserved. It involved placing a reinforced concrete slab, supported by steel brackets mounted in the load-bearing walls, in the ceiling. This method was used in two tenement houses (nos. 34 and 36). The wooden ceilings were discovered during renovation works and, because of the concrete slab, they were able to survive the war.

Hempel had a rich biography – after studying in Graz, Austria, he was called up to the Russian army and in 1914, during World War I, managed construction of bridges. After the war, he continued his studies at Warsaw Polytechnic University, with which he was associated for the rest of his life. He worked for the Warsaw Reconstruction Office as a specialist in wooden and reinforced-concrete construction. His knowledge and experience were useful in the reconstruction of the Poniatowski Bridge (1945-1946), the domes of the evangelical church at Małachowski Square (1947-1956), the archcathedral of St. John (1948-1956), Sigismund’s Column (1949), and the monument of Adam Mickiewicz (1950). He is also the author of the famous Spire in front of Centennial Hall in Wroclaw, erected for the Regained Territories Exhibition in 1948.

-

15. Fragment of a robe of the Duke of Masovia

Room of Clothing, level 2

Fragment of a robe of the Duke of Masovia

Italy, the end of 15th ct

silk damask

MHW 16677About its accidental discovery during the reconstruction of the cathedral and about the oldest fragments of robes preserved in Warsaw.

In February 1953, during the reconstruction of the nearby cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, the workers, who were installing a new central heating system, found a crypt. It turned out to be the burial place of the last Mazovian dukes – the prematurely deceased brothers Stanisław (1501–1524) and Janusz III (1502–1526).

Finding the remains of the young princes became an archaeological sensation. Inside the two-level grave, along with the skeletons, fragments of fabric, a ring and dry herbs were found. Despite difficult times, the burial site and related finds were examined by many specialists such as anthropologists, forensic doctors and conservators.

Fragments of silk and woolen fabrics, loops, buttons, and parts of a belt were probably the remains of princely costumes. Although the fragment of the fabric is quite damaged, you can still see the main pattern – rows of pointed ovals and flowers. Ovals form branches with clearly marked knots, stems and leaves. Inside the oval there is a pomegranate motif surrounded by four leaves. Under them is an open crown.

In the past, such expensive silks were created in several Italian cities: Lucca, Genoa and Venice, but also in the Middle East. They were worn at the prince’s court in Warsaw, meaning to show the courts wealth and prestige. The artifacts discovered in the cathedral crypt are the oldest instances of Varsovian clothing in the Museum of Warsaw collection.

-

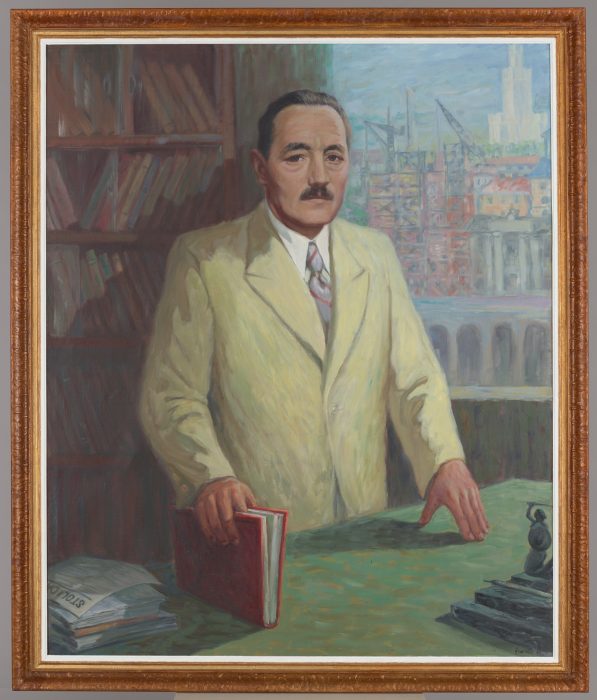

16. Representative portrait of Bolesław Bierut

Room of Portraits, level 2

Representative portrait of Bolesław Bierut

Michał Gawlak

Warsaw, c. 1955

oil on canvas

MHW 15138About the portrait, about the “Six Year Plan for the Reconstruction of Warsaw” and the Bierut decree.

This is one of the most controversial exhibits at the Museum of Warsaw. The portrait presents the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party and the then Prime Minister of the Government, Bolesław Bierut (1892-1956), the most important person in the state, the actual leader of post-war Poland.

Bierut poses standing behind a desk in his office. Work is important to him. To prove it, the painter placed here books and papers covered with the Stolica (EN: The Capital) magazine. The weekly had been published since 1946 and was devoted to the life of rebuilt Warsaw. He puts his left hand on the table top, the other on the book, which he has closed and put his finger on.

Behind Bierut we see a bookcase with books standing a bit disarranged, showing that they are used. From the window you can see the rebuilding of Warsaw and its new symbol, the Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science. The portrait was painted in 1955, the year of the building’s completion. On the desk, the Mermaid statuette confirms that the painted city is Warsaw.

Don’t be fooled by the cheerful nature of the portrait. For many people, Bierut became a symbol of Stalinist terror. He was also responsible for the so-called Bierut Decree. The “Decree on Ownership and Use of Land in the Area of the Capital of Warsaw” was published on 26 October 1945 and implemented one month later.

It established that all grounds within the territory of the capital city of Warsaw come into the possession of the municipality of the capital city of Warsaw. The decree did not nationalize the buildings themselves. This solution was adopted, as the first article of the decree states: ” In order to ensure the rational way of the reconstruction of the capital and further its development in accordance with the needs of the People, in particular with the goal of quickly acquiring the grounds and their proper usage.”

The decree, or rather its illegal execution, has become a symbol of the greatest injustice of the communist authorities towards the property of Varsovians. The idea of the decree had pre-war roots, and the idea of land communalisation, popular among left-wing urban planners in Poland, was born in Western Europe. Without this difficult decision, rebuilding the city in a new shape seemed impossible. The problems and the consequences still present today are not the result of the Decree itself, but of the faulty implementation of its provisions and the lack of political will to resolve the issue of reprivatization after ’89.

-

17. Donation for the reconstruction of Warsaw

Room of Medals, level 2

Donation for the reconstruction of Warsaw

Leon Szatzsznajder

Warsaw, 1952

bronze

MHW 4499About a new adaptation of old iconographic motifs, about money for reconstruction and the Communal Fund for Reconstruction of Poland and Warsaw (PL: SFOS).

In traditional Christian paintings, the donor kneels before their patron saint. In their hand they hold a miniature model of the chapel, church or monastery to which they have donated. This iconographic motif is being used here in a new way. Here is a barefoot woman in a simple long dress, sitting on a stool, giving a standing man a model of an apartment building. The man reaches out his muscular, weary hands. He has high boots, rolled up sleeves, an apron and a trowel tucked in his belt. He is a bricklayer. He just put down the wheelbarrow with mortar. The scene takes place against the ruins of the city. The inscription along the rim says “A donation to the reconstruction of Warsaw”.

This is one of many examples of the use of traditional motifs in new situations and for new purposes. A saint is replaced by an overworked bricklayer. And a donor is the figure of a woman – a symbol of all who contributed to the reconstruction of the city.

The donations are an important element of the history of the reconstruction. To realize such a great event, enthusiasm of the people was not enough, money was needed. It is estimated that about half of the Polish national budget in the first post-war years was dedicated to the reconstruction of the capital.

The national Communal Fund for Reconstruction of Poland and Warsaw (PL: SFOS) was created in 1948. It was headed by Marian Spychalski (1906-1980), an architect, first post-war president of Warsaw, and BOS organiser. All employees were taxed for the benefit of the Fund. The tax was small; it only amounted to half a percent of one’s earnings. Some products, including vodka, were also taxed. With the money collected by SFOS, it was possible to renovate or rebuild Nowy Świat Street, Staszic Palace, Church of the Holy Trinity, the Grand Theater, monuments of Copernicus, Chopin, and Poniatowski, Sigismund’s Column, and the palaces in Wilanów and Łazienki.

From 1958, Warsaw decided to share its fund with other cities in need. Part of the funds flowed to the reconstruction effort in Gdańsk, Poznań and Kraków. After that, the name was changed to: Communal Fund for Reconstruction of Country and Capital (PL: SFOKiS). In 1966, when it was recognized that the reconstruction was over, SFOKiS transformed into the Communal Fund for the Construction of Schools and Boarding Schools, serving the needs of a growing society.

-

18. Design of a commemorative medallion containing a lump of rubble

Room of Relics, level 3

Design of a commemorative medallion containing a lump of rubble from Warsaw destroyed after the World War II

Stanisław Kurman

Warsaw, 1947–1952

cardboard, aluminum sheet

MHW 25923About the rubble of Warsaw and its symbolic meaning.

After the failure of the Uprising in 1944, Warsaw was a sea of ruins. Almost 80 percent of the pre-war buildings had become rubble.

Some of the debris was removed and some was used as landscaping material, one example being the ramparts of the former 10th-Anniversary Stadium (today, National Stadium). The Muranów district’s apartment blocks also stand on rubble. Whatsmore, the blocks themselves were also built from ground debris. Szczęśliwicka Mound and the Czerniakowska Mound at Bartycka Street were also built of rubble.

The unrealized project of a two-sided, probably opened medallion was created by the Warsaw artist Stanisław Kurman. In the middle of the medallion was a clod of rubble from Warsaw after World War II. On the medallion are the Virtuti Militari Order, the Warsaw Mermaid and the inscription “Warszawa”.

Virtuti Militari is the highest military decoration “in recognition of the heroic, persistent bravery proven by the population of the capital city of Warsaw in defense against the German invasion,” awarded to the city on 9 November 1939 the Prime Minister, Supreme Commander, Major General Władysław Sikorski.

The custom of storing small fragments of rubble has its origins in ancient times. It probably came from the tradition of wearing amulets, objects protecting its wearer from misfortune. Later, this role was played by the relics of saints worn in medallions. The secular version of these relics were souvenirs of loved ones: hair of a fiancee, parents or children, dried flowers, painted or photographic portrait miniatures. In the more recent past, a similar role was played by photos in wallets and now in telephones, contemporary storage media.

This medallion is unique because it was supposed to contain bits of the ruins of the beloved city. It was meant to recall its destruction. Small parts of Warsaw were planned to be distributed around the world among Polish emigrants to remind and to encourage the Polish community to support the reconstruction.

-

19. W-Z cigarettes pack

Room of Warsaw Packaging, level 3

W-Z cigarettes pack

W-Z Wrocław Cigarette Factory

after 1949

cardboard, paper, print, factory product

MHW 25573About the propagandistic significance of the W-Z Route and the escalator.

In the mid-20th century smoking enjoyed immense popularity. Cigarette packs became a vital carrier of propaganda. Almost everyone smoked – youths, elderly people, women, intellectuals, labourers – therefore propagandistic content could reach a truly wide audience.

Cigarette packs were ideal for propagating the idea of the joint effort. The W-Z cigarette pack is a perfect example. The front side features the new symbol of reborn Warsaw, the W-Z (East-West) Route built in 1947-1949, depicted synthetically in a two-colour graphic representation.

In September 1947, during the 800th anniversary of the founding of Moscow, the government promised that Moscow would give the destroyed city all the equipment to build an escalator for the W-Z Route. Escalators were meant to be an important element of the Route and a new attraction for the residents of the capital. The propagandistic significance of the gift would be serious.

It didn’t go so smoothly. The promise was forgotten. Finally, after the intervention of the authorities, the stairs were purchased in the Foreign Trade Union of Machine-Import.

Due to the length of the stairs (30 meters), it was decided to extend one of the tenement houses being rebuilt to the north. In this house is an exit from the tunnel connecting the lower part of the route with the upper part at the Royal Castle Square. The entire basement of the tenement house was occupied by a stair engine room weighing almost 150 tons. The stairs, as predicted by the authorities, quickly became a tourist attraction.

-

20. Observation point

fot. m. st. Warszawa

About being inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

You are at the highest possible point of Old Town. From here, you can see reconstructed houses and churches, the Royal Castle and the city.

This effort and the enthusiasm of architects was recognized by UNESCO by inscribing Warsaw’s Old Town on the Heritage List in September 1980. This was the first historical reconstruction inscribed on the list. It was an expression of great respect and admiration for the Polish architects, conservators, historians and art historians who undertook something unprecedented in history – reconstruction of an almost completely ruined historical center of a city.

The Warsaw Reconstruction Office, in operation until 1951, left many maps, plans, projects, inventories and photographs. In 2011, 14,000 of those documents were inscribed on the UNESCO World Memory list. This list gathers documentary heritage objects of special global significance.

-

21. The Heritage Interpretation Centre

fot. Muzeum Warszawy

Centrum Interpretacji Zabytku

ul. Brzozowa 11/13

00-278 WarszawaAbout the Museum.

The permanent exhibition of the Heritage Interpretation Center, entitled Destruction and Reconstruction of the Old Town, presents the story of Warsaw’s Old Town before, during and after World War II. It focuses on its reconstruction and inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

There you will find materials showing damage from the war and photos from subsequent stages of reconstruction, supplemented with information about the Warsaw Reconstruction Office (BOS). At the exhibition you can also see photos of the most important architects and their studios, and deepen your knowledge of the reconstruction and the people responsible for it by with multimedia displays of maps, biographies, radio broadcasts and archival films.

Our museum organises lectures on the subject of post-war reconstruction, but also undertakes other Varsovian topics as well as those related to UNESCO world heritage and its mission.