20.09.2023 / Activities, News

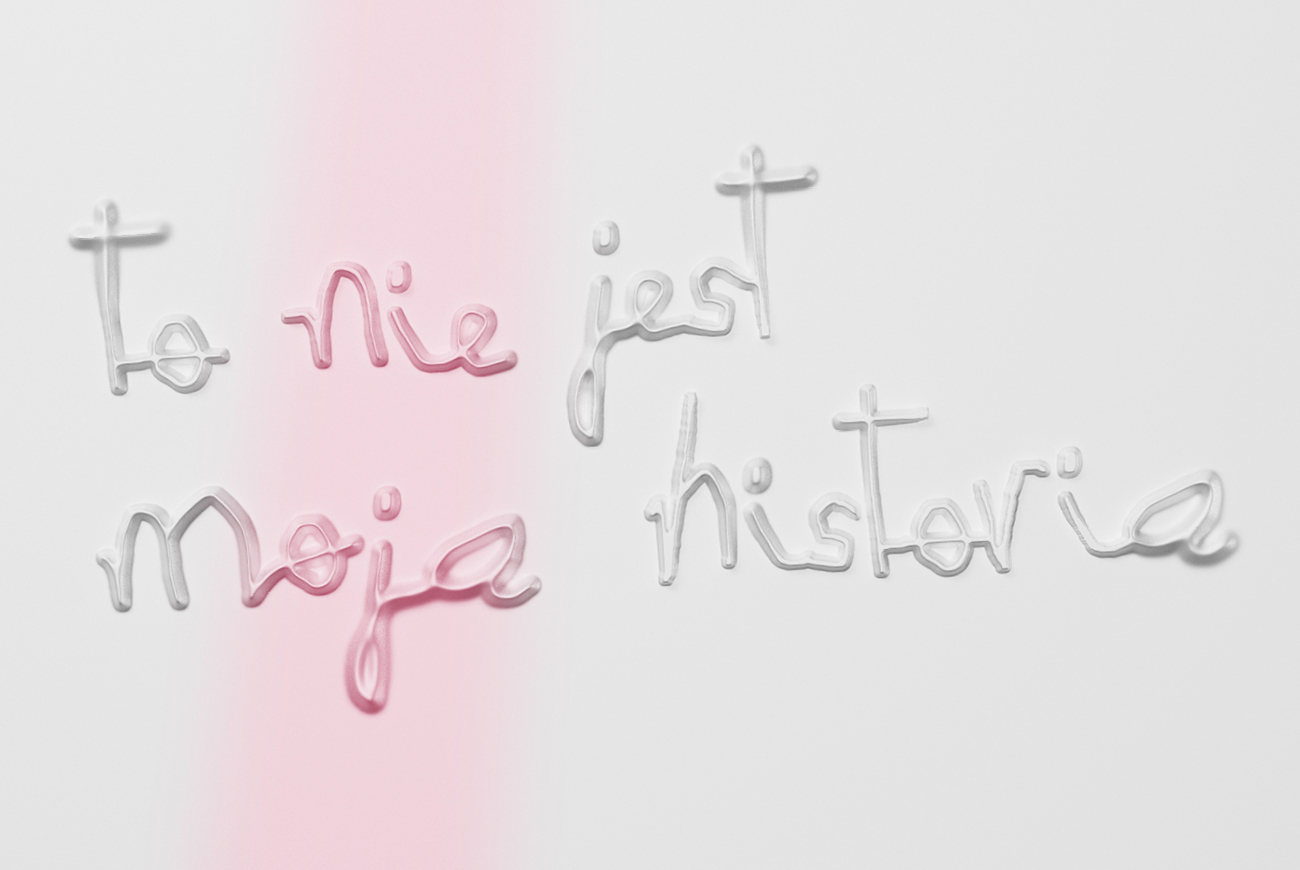

This is Not My Story. Warsaw Childhood Around 1900

The pathway through the permanent collection of the Museum of Warsaw has been inspired by the book by the German Jewish writer and philosopher, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) Berlin Childhood Around 1900.

This book cannot justly be considered as an autobiography; rather, it is a constellation of Benjamin’s memories and impressions of his childhood, spent in an upper-middle-class Jewish home in West Berlin at the turn of the 20th century. It’s a record of rummaging in memory populated not so much by people or events, but by things and places. All of which are seen from a child’s perspective and transformed by its imagination.

The path leads through ten points – cabinets or individual objects – accompanied by texts inspired by Benjamin’s recollections.

Berlin Childhood Around 1900

In Benjamin’s book, we find a montage of passages devoted to the experience of different seasons of the year or days of the week, truancy and vacations, great celebrations, visits to relatives, illness, or travel.

The narrator anchors his story at various points in time and with a constantly changing topography. We enter this world with all our senses. A similar experience is offered by the pathway through the collection.

Benjamin’s fascination with childhood was primarily related to the puzzling state of a child’s mind, which – still clumsy and unrefined – deforms or distorts the world in the most creative ways. The philosopher closely observed the growth of his son Stefan. He took notes on the child’s expressions, word games, shifts of meaning, absurdities and “mistakes.” It is the distortion (German: Entstellung) that becomes the leitmotif of Benjamin’s experience of himself as a child:

If I distorted myself and the word on this occasion, I was only doing what I had to do to catch ground [catch ground doesn’t make sense in English] in life. (The Mummerehlen)

The museum exhibition (German: Ausstellung) is also a (necessary) distortion of the represented world (in this case, Warsaw), and at the same time its most actualized historical representation at the present moment. Objects congealed in the realm of memories by the power of language reveal their mutual references and connections. The same happens in the exhibition. As a result of displacement and distortion, new connections between things and new histories of places are created, and with them, new impressions and experiences of the past. The world of childhood remains unrecoverable as a social reality; it can only be imagined as a magical one, enchanted in language and in objects. To enter this world, one needs the childlike gift of procrastination, absorbed looking, unhurried snooping, arranging things in one’s own way.

The pathway through the permanent collection of the Museum of Warsaw

We invite you to tune into this rhythm. Our exhibition offers a glimpse into a journey back in time, to the world of an upper middle-class Warsaw child narrated by the lives of the objects. They drive memory and with their assistance one constructs (not) one’s story.

The exhibition accompanies an academic conference of the International Walter Benjamin Society, which takes places in Warsaw September 27-30, 2023.

More information: walterbenjamin.info

The points of the tour path are marked with placards in dark green.

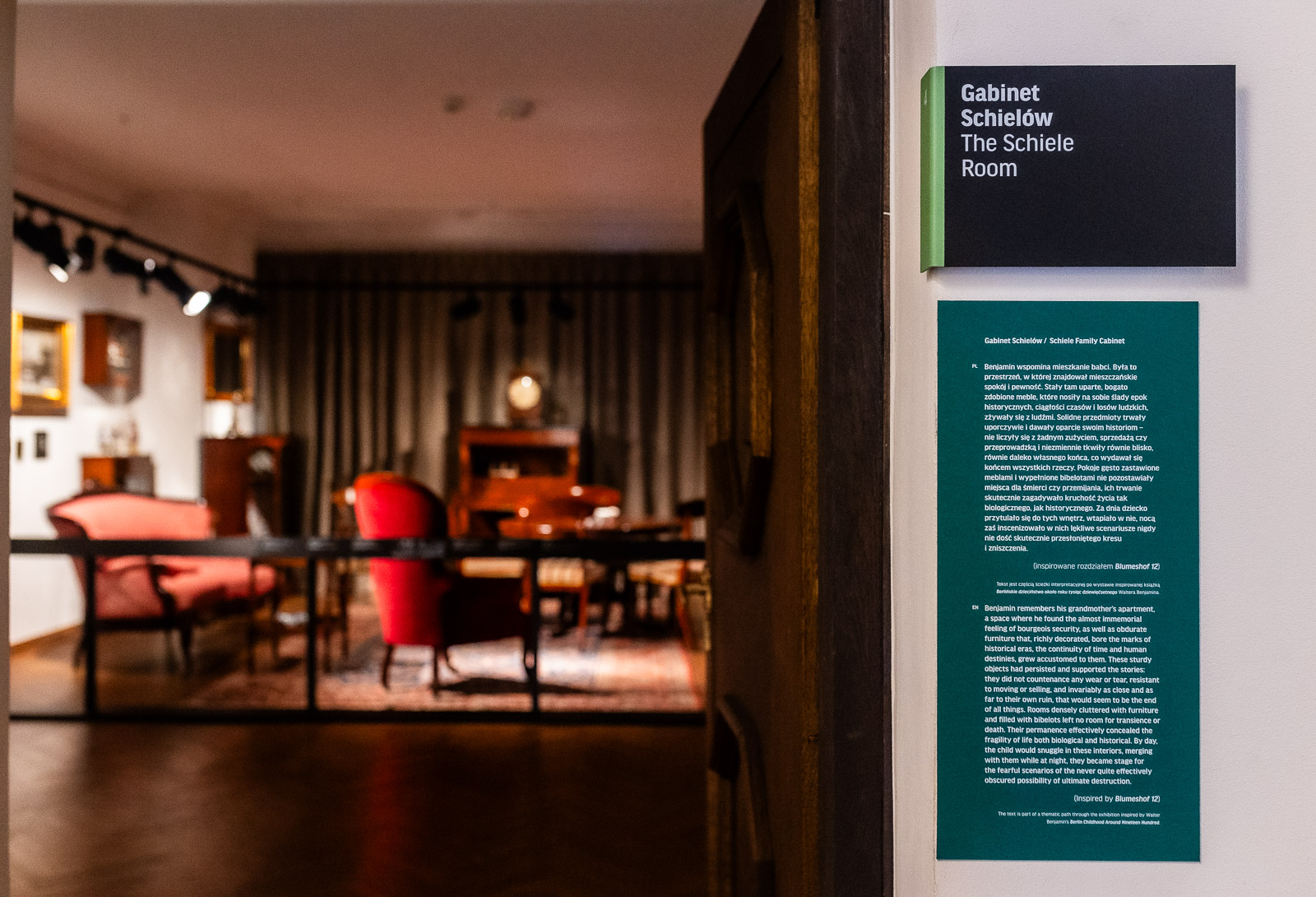

The Schiele Room

Benjamin remembers his grandmother’s apartment, a space where he found the almost immemorial feeling of bourgeois security, as well as obdurate furniture that, richly decorated, bore the marks of historical eras, the continuity of time and human destinies, grew accustomed to them. These sturdy objects had persisted and supported the stories:

they did not countenance any wear or tear, resistant to moving or selling, and invariably as close and as far to their own ruin, that would seem to be the end of all things.

Rooms densely cluttered with furniture and filled with bibelots left no room for transience or death. Their permanence effectively concealed the fragility of life both biological and historical. By day, the child would snuggle in these interiors, merging with them while at night, they became stage for the fearful scenarios of the never quite effectively obscured possibility of ultimate destruction.

(Inspired by Blumeshof 12)

The child is caught by the sight of a decorated plate: the child’s gaze travels along the trail of patterns, blue threads, branches, flowers, indulges in this escapade without restraint. The child doesn’t want to have food, he wants to have fun. He vies for the favor of this unheard of, yet seen every day, onion pattern. He desires to befriend it, find an ally of play and discovery, so he stares at it again and again.

However, this elegant, noble antique rejects the favor of the child, remains cold and flat. The pattern creeps on its trail, does not advance to meet the child, rejects its gaze, does not even blink a leaf. There will be no alliance, only eternally renewed trials.

(Inspired by Society)

The Ludwik Gocel Room

The charm of books, and the child’s love for them did not depend at all on their content, literary merit, place in the canon or critical acclaim. Above all, their charm prevailed because they were not textbooks or assigned readings, which like barracks, imprisoned the young readers in the depths of boredom and literary mustiness.

The books in the library offered respite and relief from this boredom and the predictability of the school’s regime. They provided access to a different world, which could be read on one’s own terms, without the mediation of a teacher. This world was inhabited by mysterious characters and objects, that eagerly entered the spaces of one’s imagination and one’s room, ready to leave the illustrations and make themselves comfortable next to the home’s furniture, match the patterns of its fabrics.

One could get lost and shake with terror, experiencing that formidable fun of unforced and unrestrained reading pulled from the darkness of a bookcase.

(Inspired by School library)

Stove

A hiding place allows one to be in the world of matter, to be close to it, so close as to momentarily become indistinguishable from it. It allows one to hide from the gaze that will recognize the little human in us, find us and call us for dinner.

Just as a child is transformed under the influence of a hiding place, so a hiding place from an ordinary table, cupboard or stove transforms before his very eyes into a jungle, a temple, an echo chamber. The joy and horror, the surrender to the seeker and the relief of remaining hidden all lend the game of hide-and-seek a special chilling delight.

The apartment has never been simply safe, it has always already been a space of uncanny possibility of not-being-in-view, of not-being-oneself, of this inconspicuous survival, or of enchanting reality.

(Inspired by Hiding Places)

Room of Clothing

Mother had numerous pieces of jewelry. Each of them could easily become the hero of its own crazy adventure.

The mother had an ornament in the form of interconnected rosettes – what held them together and why? I wonder if wearing it on the bodice would not have been too grotesque, shouldn’t it rather have been pinned to the waist, or perhaps under the neck?

The ornament was made of transparent, flesh-colored fabric, with an irregularly wrinkled surface; as such it resembled a body part, something that could grow on the skin, and was thus disturbing. Or perhaps as this ornamental growth – similar to, and yet separate from the mother’s body – it could serve as a talisman to protect her from any possible danger. And as such, it fascinated and terrified.

(Inspired by Society)

Room of Silverware and Plated Silverware

The times when society made its way to the house prompts the experience of excitement and sadness at the same time. Setting up the table, bringing out the extra tableware, expanding the table space, preparing the settings, touching all those elegant utensils for exquisite food, for the sophisticated gourmet and those everyday utensils so well known to the child. On that day they all become part of that distinguished society. The child runs his fingers over the richly decorated knives and forks. He runs his eyes over the glittering knife blades, fine-cut little glasses, filigrees on silverware, looks into the depths of the goblets hearing the murmur of the poured liquids and strokes the bizarre gnomes and animals that decorate the bottle stoppers.

Finally, the child arranges the name cards for the guests, reciting the attendance list in his mind and, for that one moment, becoming the conductor of this entire dining room orchestra.

(Inspired by Society)

Room of Bronzes

The gift of perceiving similarities which an adult possesses, is a remnant of the familiar childhood compulsion to resemble others and behave as they do. This is called life learning and the world learning process.

But how does one become similar to oneself? How does one connect with one’s own image in a photograph if one always sees someone else already there. In the photographic studio:

I saw myself surrounded by folding screens, cushions, and pedestals which craved my image much as the shades of Hades craved the blood of the sacrificial animal.

The child poses with a tortured smile, in clothing that is a disguise, against a decorative backdrop, a tacky landscape that is more dead than the surrounding still life. The only thing that seems more inanimate is the potted palm tree. And a click of a shutter. Forever a frozen me-not-me, framed, gazing at anyone who wishes to recognize me in me.

(Inspired by The Mummerehlen)

Room of Warsaw Monuments

It stood on the wide square like a red-letter date on the calendar.

As reported by Albrycht Radziwill, King Wladyslaw IV Vasa ordered the houses of the Bernardine Monastery to be demolished in order to erect the column – the oldest secular monument in Warsaw and the first secular column in modern Europe. Although it’s rather difficult to guess, since the King holds a cross anyway. It’s hard not to admire the Hero with a sheathed saber. In order for the King to tower over the city and the world, urban buildings had to be destroyed. It’s impossible to look him in the eye, he towers so high.

And as the inscription on the north side of the monument says, Sigismund’s fame is not due to this column, because “he was towering above himself.” It’s hard to comprehend how this happens, in the sunshine of the eternal Sunday. It’s equally hard to imagine that the ruler’s saber descends when the city is threatened and rises upwards when the city triumphs.

(Inspired by Victory Column)

Room of Postcards

First of all, why was the market hall replaced by the House of the Polish Word? What does it mean that the word (Polish) has a house. What does one do in such a house? What an extravagance to give this name to the largest printing plant in the People’s Republic!

The Polish Word took up residence there replacing the market square named after the capital’s president Kalikst Witkowski, who left office in 1875. Hay, oats, potatoes, wheat were traded here – something for the carriage horses and something for the kitchens of the men and women of Warsaw who lived nearby.

The market halls were welcomed as the home of modern commerce. They had brick facades in a modernized Romanesque and Gothic style, the main facade was decorated with a tower and spire, and the side facades were decorated with sculptures and bas-reliefs by Zygmunt Otto. They depicted fowl, fish, game, crayfish and genre scenes. True commercial art. In the center of the hall the priestesses of commerce ruled, and under the ruffles of their skirts real treasures were gathered: mushrooms, berries, cabbages, beets…. The priestesses led the way with their eyes blessing the housewives and servants seeking good fortune with groceries.

(Inspired by Market Hall)

Room of Warsaw Views

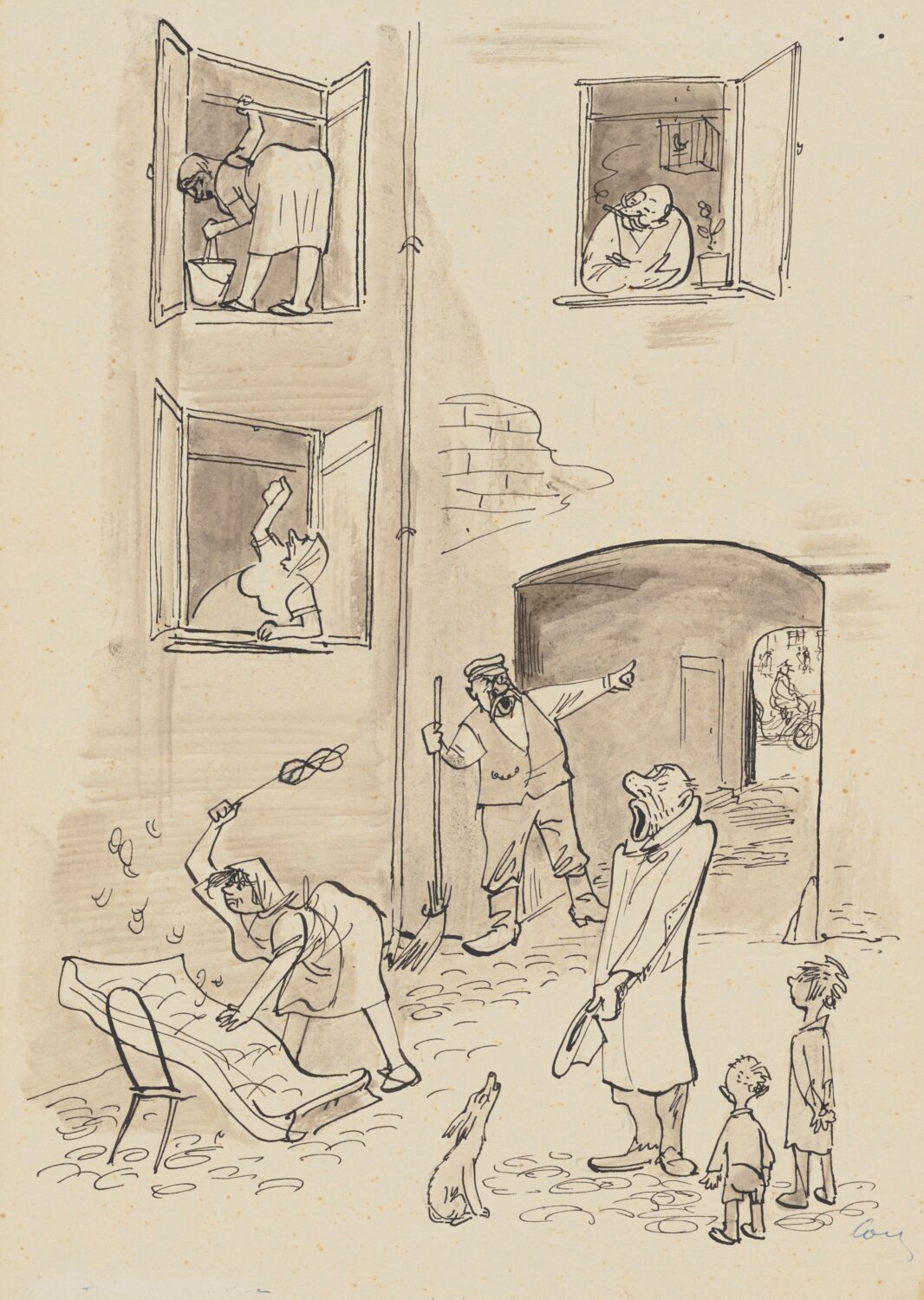

Listening to the sounds of the street, the symphonies of the courtyard. One of the most profound sounds was the beating of carpets in the morning.

The steady beats that once aligned with the heartbeat of the listener, at other times diverged from it. The raucous pounding of the weave of fabrics wafted in through the open window and was the most momentous sign of ordinary bustling.

The carpet-beating was the idiom of the underclass, of real adults; that never broke off, always knew what it was about, and often took its time; that, indolent and subdued, found itself ready for anything, and sometimes fell back into an inexplicable gallop, as though they were making haste down there before it rained. Or before something else. What could that be?

(Inspired by The Fever)

Museum of Pharmacy

In sickness, confined to bed, the child learns the hardship of high mountain crossing, climbing the cliffs of the pillows, penetrating the dangerous caverns of the undulating quilt, slipping into the gullies as the fever drops and sweat shines on the forehead.

At hand, all those awful concoctions and remedies to save a life that was not, after all, endangered, spoons approaching the mouth, smelling bitterly, unfriendly.

The mother, persistently and cunningly administering salutary liquids and pills, becomes either a mountain guide, or a chamois leaping over the cliffs of coughing, finally settling like a tender evening mist, stroking the restless hair of the climber repeating requests for the tale she will spin, leading him along the safe trail to sleep, to health.

(Inspired by The Fever)

The text is part of a thematic path through the main exhibition of the Museum of Warsaw, inspired by Walter Benjamin’s Berlin Childhood Around Nineteen Hundred.

Additional information can be found at: muzeumwarszawy.pl/en/wystawa/this-is-not-my-history/