18.07.2024 / Activities, Hall of Remembrance at the Warsaw Insurgents Cemetery, News, Walking tour

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944

A trip through history that reveals the dramatic events of August and September 1944.

A map of the walk can be found below. Source materials – memoirs and photographs – will provide a new look at the area. The points of the walk are accompanied by recordings. If you do not have the opportunity to listen to them, you will find transcriptions below the recordings.

Start by listening to the introduction.

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 – one of the largest acts of military resistance in Europe during the Second World War – was an attempt to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany’s brutal occupation. The Uprising took place when the Soviet Union’s Red Army was advancing towards Poland from the East, while the Allied forces were making progress from the West. However, despite the Polish resistance’s appeals for support, the Soviet forces stationed on the outskirts of Warsaw did not intervene to assist the Home Army against the German occupation. Some historians argue that Stalin was hesitant to support the Polish resistance, as he had his own post-war plans for Eastern Europe. Despite the lack of Soviet assistance, the Home Army fought against the German forces for 63 days before being overwhelmed. The aftermath of the failed uprising was devastating, with an estimated 18,000 military and 150,000 – 180,000 casualties. Warsaw was left in ruins. Today, the Warsaw Uprising remains a significant yet controversial event in Poland’s collective memory. Some view the Uprising as a heroic and patriotic act, while others question its timing and strategic feasibility, especially in view of its devastating death toll.

We invite you to join us for a guided walk around the Warsaw Old Town, which was one of the main strongholds for the Home Army during the Uprising. The narrow streets and alleyways of the Old Town provided opportunities for guerrilla warfare tactics against the occupying German forces. The Old Town also symbolised Polish heritage, making it an important point for the Uprising in rallying support and boosting morale among the fighters. The walk will not only help you better understand Warsaw’s topography and history, but also experience the many ways in which the Uprising is remembered today.

How to prepare?

Bring headphones, a charged phone or take a powerbank, and put on comfortable shoes (cobblestones).

Duration: about 1,5 hour

For whom: English-speaking youth and adults curious about the history of Warsaw

We begin our walk in front of the Warsaw Uprising Monument in Krasiński Square. Find the starting point on the map. The map will help you to locate the other stops and places that we will talk about.

Authors: Education Department

Consultation: Julian Borkowski

Recording: Hanna Tomaszuk

Lector: Michalina Sozańska

Warsaw Uprising Monument

We begin our walk in front of the Warsaw Uprising Monument in Krasiński Square. Made up of two sculpture groups, this monumental memorial is impossible to miss. Look at the first group of sculptures, placed directly in front of the Supreme Court building. Notice how the figures of the insurgents emerge from under the stone pillars. Now turn away from the Court building toward the street and notice the second, smaller group of figures. Here, soldiers and civilians are shown going down into the sewer – an event which took place during the evacuation of the Old Town, and a well-established symbol of the Uprising’s defeat.

Today, the monument in Krasiński Square is the most important commemorative site linked to the Warsaw Uprising. However, the story of its construction was not easy. Unveiled in 1989, almost half a century after the events of 1944, the monument is the product of long struggles over the collective memory of the Uprising. Attempts to build a permanent, public memorial of the Uprising began soon after the Second World War. However, they were delayed by political conflicts over how – and if – the events of 1944 should be remembered. Poland’s postwar communist government saw the myth of the Uprising as a threat to its political legitimacy. The significance of the uprising was downplayed for many years after the war, and the Home Army and the wartime Polish government-in-exile were condemned by communist propaganda. For that reason, attempts to establish a permanent memorial of the Uprising were repeatedly rejected.

The government’s policy changed only in the last years of the communist era. When the Solidarity movement began growing in strength, the myth of the Uprising took on new political meanings. Initiated in the early 1980s, a popular campaign to build a memorial of the Uprising was seen as a way of defying the communist state’s monopoly on collective memory, and a way of connecting with a long tradition of national resistance. Ultimately, the monument was unveiled in Krasiński Square on August 1, 1989 – the forty-fifth anniversary of the outbreak of the Uprising – and here it stands today. As such, the Warsaw Uprising Monument is not only a commemorative site, but also an example of the social and political forces which shaped Poland’s postwar memory culture.

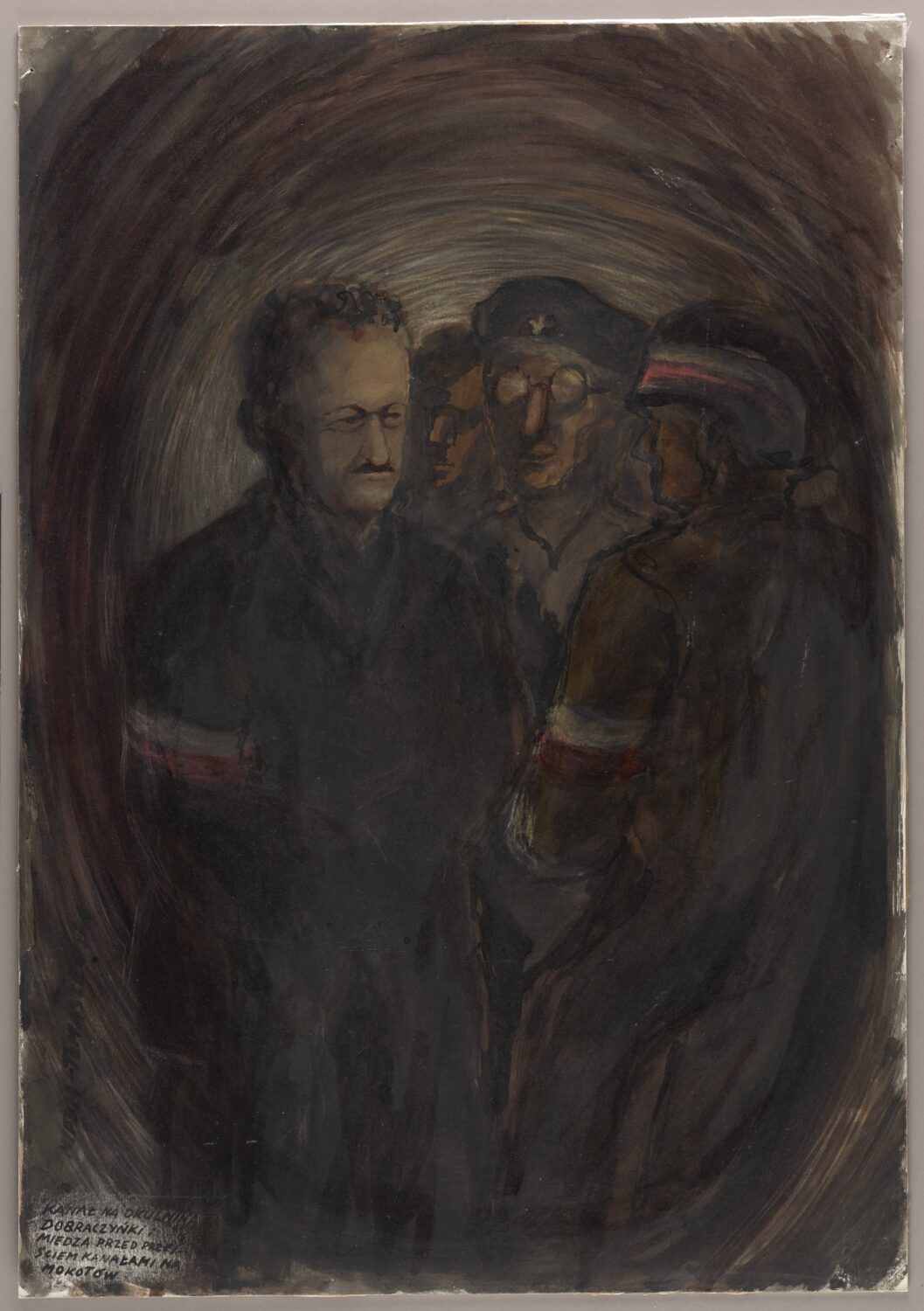

Entrance into the sewers

Next, stand at the intersection of Miodowa and Długa streets. In the middle of the street you should see a line of dark cobblestones which lead to a sewer manhole. This specific manhole has special historical significance. In late August and early September of 1944, as German and collaborationist forces were closing in on the area, over five thousand people evacuated from the Warsaw Old Town into the city centre using the underground sewer network. Most insurgents and civilians went down into the sewers through this access point, and exited in Warecka Street near the Nowy Świat Street. On the yellow building in front of you, you should find a plaque commemorating this event. Here, you can trace the underground route taken by the evacuees. About 1.5 km long above ground, covering this distance underground required about six hours of walking through the sewers.

The city’s underground sewer network had been used as a line of communication throughout the Uprising. It was extremely dangerous and highly uncomfortable. The sewers were cramped, dark spaces filled with sewage and waste, many of them only 90 cm high and 60 cm wide. In addition, the German army quickly realised that the insurgents were using the city’s sewer network to move around the city undetected and tried to impede their underground movements by throwing grenades, smoke bombs and gas canisters inside the tunnels. Immortalised in Andrzej Wajda’s famous film Kanal which won the Special Jury Award at the 1957 Cannes Film Festival, the experience of people fleeing for their lives through the sewers was especially dramatic. Walking through the sewers in complete darkness, they had to move silently to avoid being discovered by Nazi troops.

Monument to the Women of the Warsaw Uprising

Near the Krasiński Palace, right at the entrance to the park, you can find a bronze monument depicting three female figures holding hands. Created by artist Monika Osiecka in 2021, this memorial concludes long-standing efforts to spotlight women’s involvement in the Warsaw Uprising. Even though women represented 22% of participants in Uprising, for decades they were marginalised in the historiography and memory of the insurgency. Women were engaged in the underground resistance throughout the entire period of the occupation, especially in sabotage and intelligence units. During the Uprising, they played a crucial role in various capacities. They provided medical assistance as nurses, distributed supplies, served as couriers, and were involved in direct combat as fighters. After the war their contributions were sometimes disregarded and unrecognised. However, it has been changing for the last few years. The female point of view has been strongly emphasised. There are many books of women’s memoirs being published. Today, the monument serves as a reminder of the significant role women played in the Warsaw Uprising and highlights the importance of recognizing their contributions.

Field Cathedral of the Polish Army, Długa Street 13/15

Back on Długa Street, across the street from the Warsaw Uprising Monument, there is a Baroque church. You should be able to recognise it by two characteristic objects placed near the entrance: an anchor and a propeller, symbolising Polish navy and aviation forces who died in the Second World War. The military symbols weren’t placed here at random – the building in front of you is the Field Cathedral of the Polish Army, the largest garrison church in Warsaw. It was also an important site during the Uprising. The cathedral’s Western tower was used by insurgents as an observation point. For some time, its crypts were utilised as an emergency field hospital. As a result of its strategic importance, the building sustained extensive damage during bombardment by the Luftwaffe. Today, it houses a small museum dedicated to the history of military ordinariate.

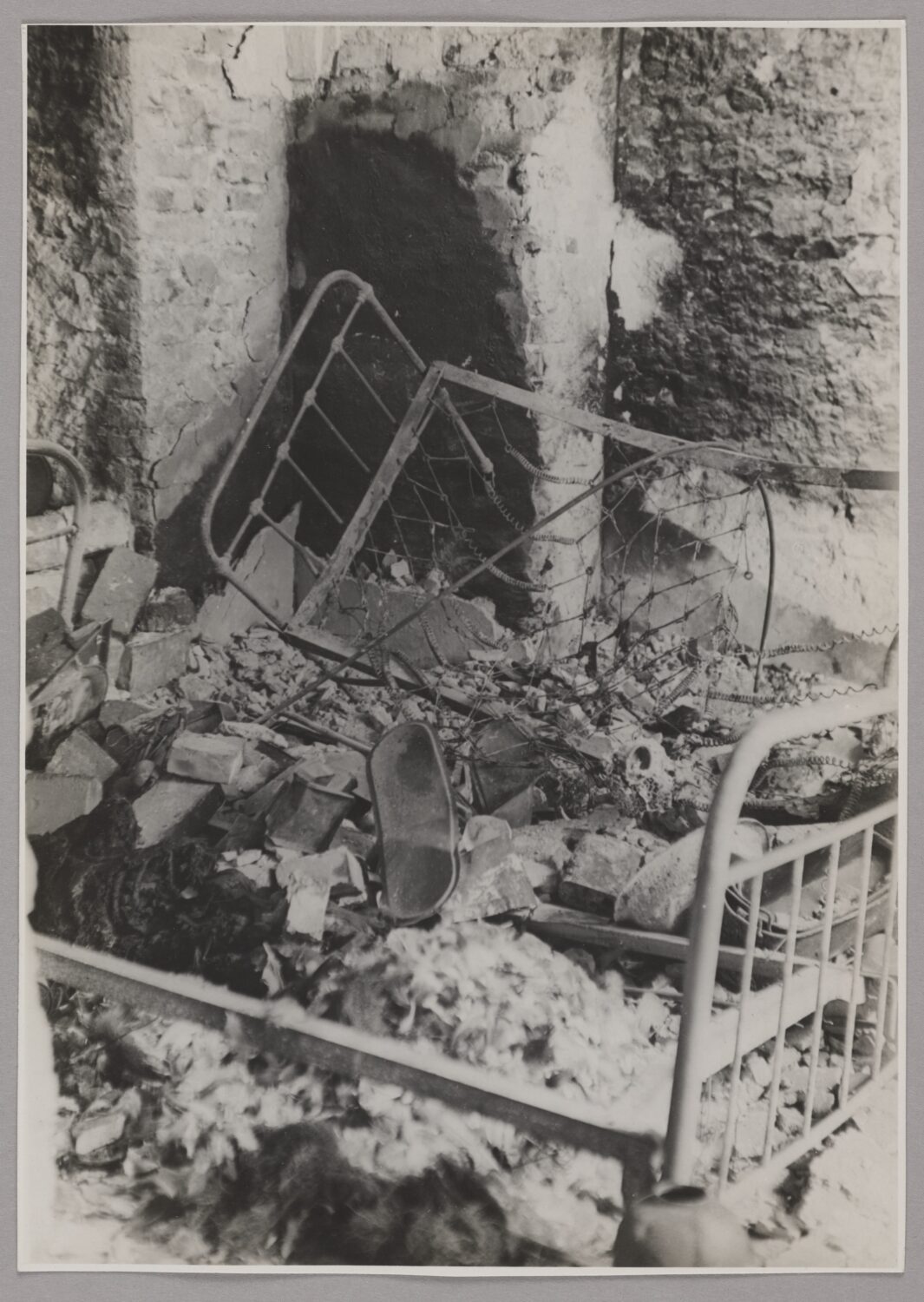

Field hospital at the Raczyński Palace, Długa Street 7

After a short walk down Długa Street, you should arrive at the Raczyński Palace. This large classicist building – which used to house the Polish Ministry of Justice in the interwar period – became a key location during the Uprising. As the German offensive kept advancing towards the Old Town, the number of insurgents and civilians who were injured and required urgent medical attention was constantly increasing. Because existing hospitals were located too close to the front line and were being heavily shelled, on August 12 the Raczyński Palace was adapted into the Central Surgical Hospital. Originally meant only for combatants, the building quickly filled with both military and civilian victims and became the largest field hospital within the entire Old and New Town area. On August 13, the building received people injured in the explosion of a tank bomb at Kilińskiego Street.

When the evacuation of the Old Town began in the last days of August, many of the injured from the hospital in Długa Street, and some of its staff, escaped through the sewers. A dozen or so doctors and nurses chose to stay with the heavily wounded. They destroyed all physical evidence of their patients’ involvement in the insurgency, hoping to convince the German army that the hospital was a civilian unit. However, the Nazis had no regard for conventions guaranteeing the protection of wounded and sick soldiers, or sanitary and civilian aid services during combat. When Waffen-SS units entered the Old Town, they systematically liquidated all the field hospitals. In the Raczyński Palace, they brutally executed 430 people and burnt their bodies. Near the building’s left edge you can find a memorial plaque commemorating this massacre. Currently, the palace houses the Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw.

The corner of Długa and Freta Streets

Stop at the corner of Długa and Freta Streets. An incredible story of love and survival took place here. On September 3, a group of wounded insurgents who managed to escape from the massacre of the surrounding field hospitals hid in the basement of a house on the corner of Freta Street. The group was cared for by Danuta Ślązak (codename „Blondie”), a senior riflewoman who had come to one of the field hospitals to visit her commander Mieczysław Gałka (codename „Elegant”). The two of them, along with one other soldier, managed to survive in the basement until October 7, when Danuta ventured outside to find help. Unfortunately, at the hospital, it turned out that Elegant’s leg had to be amputated. Desperate, Danuta promised to wait for him and convinced him to live. On April 15, 1945, Danuta Ślązak „Blondie” married Mieczysław Gałka „Elegant” in Warsaw’s Praga district. In the 1990s, she published a memoir detailing her wartime experiences titled I Was a Warsaw Robinson.

The „Robinson Crusoes of Warsaw” was a name given to the people who hid in the city’s ruins after the fall of the Uprising, sometimes living in basements and bunkers for weeks or months. Of the approximately 1,000 Robinsons, the majority died in hiding, yet some – like Danuta Ślązak – survived. The most famous Robinson of Warsaw was Władysław Szpilman, the Polish-Jewish composer and Holocaust survivor whose life story was adapted into the Oscar-winning film The Pianist.

St. Hyacinth's Church, Freta Street 10

Turning into Freta Street, you will see a Baroque church on your right. During the Uprising, St. Hyacinth’s Church – founded by the Dominican Order in the 17th century – housed another field hospital in the area of the Old Town. When the surgical hospital in Długa Street began struggling with the rapidly increasing number of patients, some of its medical staff moved to Freta Street to start an affiliate facility on August 19. Simultaneously, the Dominican Church began to take in civilians seeking shelter from constant bombardment. The building’s solid walls gave them a sense of relative safety. Tragically, the fact that the church provided a refuge for so many people meant that when it was bombed by the Luftwaffe on August 27, the attack claimed hundreds of lives. Most were killed in the explosion or were buried under the rubble. However, the fate of those who survived the initial bombing was equally horrendous. After the German Army entered the Old Town on September 2, the ruins of the church were set on fire and its occupants were brutally massacred.

The exact number of people who were killed inside of St. Hyacinth’s Church is still unknown. In 1945, following exhumations conducted by the Red Cross, some of the victims of the bombardment were laid to rest in a cemetery in Wola. Unfortunately, many remains were likely never recovered and properly identified. The church was fully rebuilt in the 1950s at the insistence of Professor Jan Zachwatowicz, the main architect of the Old Town’s postwar reconstruction. However, it’s possible to find some traces of the damage the building sustained during the Uprising. In the garden, a fragment of the wall still bears bullet marks. Once you go inside the church, you can also see a heavily fractured 17th century stone tomb in the right nave.

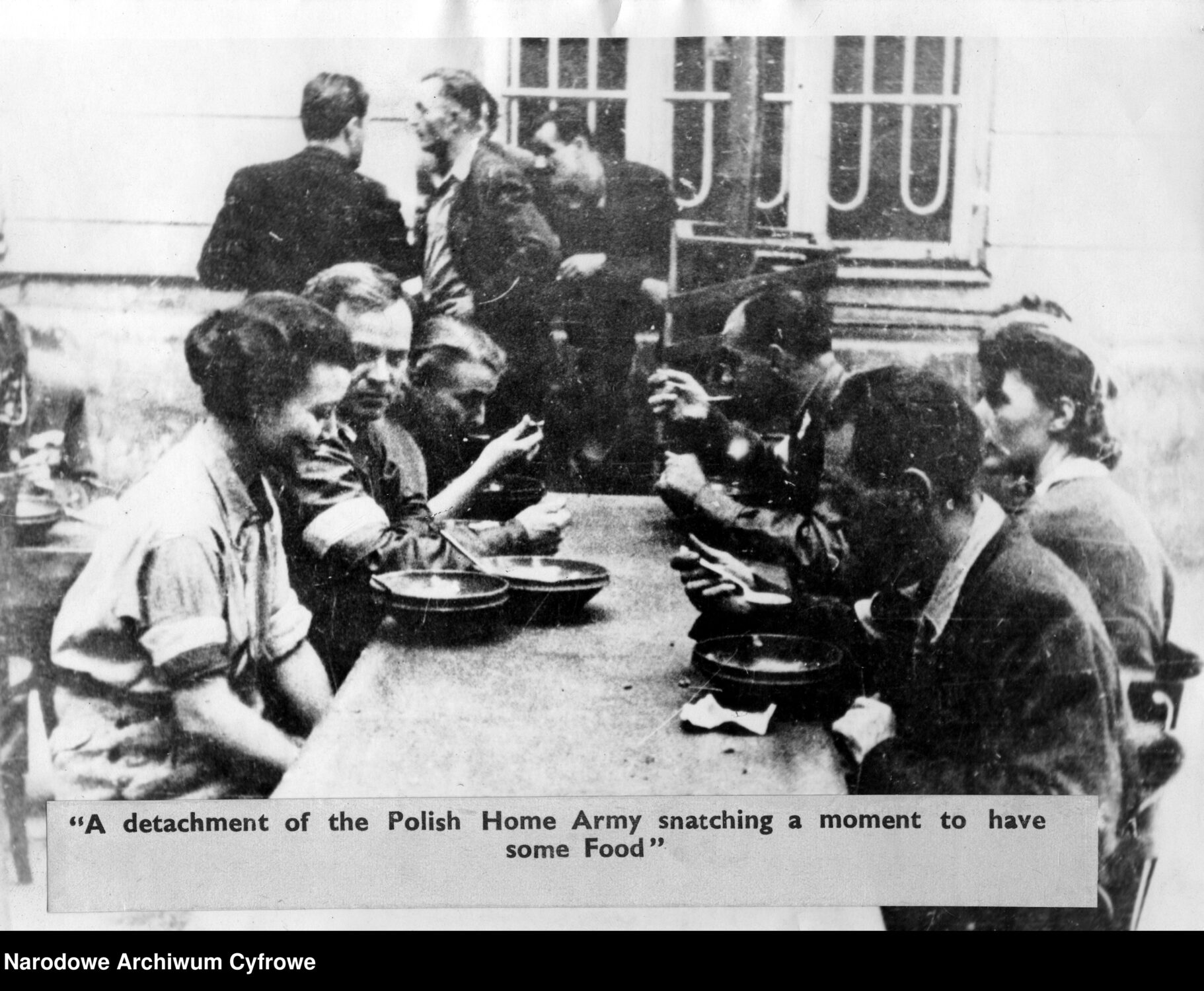

House in Mostowa Street 27/29

In the first days of the Uprising, the house on the corner of Mostowa Street is said to have housed the last open grocery store in the area. Soon, obtaining food became one of the primary daily challenges for the Old Town’s civilian population. Access to foodstuffs had been a problem for Warsaw’s inhabitants since the beginning of the occupation. However, the situation became much more dire after the beginning of the Uprising. Not only was the Home Army insufficiently supplied with food, it also never managed to seize the city’s water pumping stations, which allowed the Germans to shut off water access to the areas controlled by the insurgents. After the Home Army lost control over a Waffen-SS warehouse which it had held since the beginning of the Uprising, people began to face extreme hunger.

In the face of decreasing access to food and water, Benedictine nuns from a nearby convent in the New Town Square became the last source of provisions to many. As Miron Białoszewski, one of Poland’s most innovative postwar poets and writers noted in his Memoir of the Warsaw Uprising:

„Those Sisters of the Holy Sacrament who for hundreds of years […] had sung behind gratings and taken Communion through gratings, suddenly became activists, social workers, a heroic institution, the support of Nowe Miasto. They provisioned part of the troops, too. The troops distributed some of theirs to civilians. Only, the same error was committed every day in a vicious circle. It was hot. And they didn’t distribute the meat from the pigs and cows that had just been butchered but only those slaughtered yesterday or the day before yesterday. And the ones from yesterday or the day before were already putrid. And when the troops cooked it (because the troops did cook it), in the central shelters, in cauldrons, the stench pervaded the entire cellar”.*

*Miron Białoszewski, A Memoir of the Warsaw Uprising (New York: New York Review of Books, 2015), translated from the Polish by Madeline G. Levine.

Museum of Warsaw, Old Town Square 28-42

During your walk, we encourage you to visit the Museum of Warsaw. Located in historical tenement buildings around the Old Town Square, the museum explores the city’s long history – from its mediaeval origins until the present day. In the museum’s permanent exhibition titled The Things of Warsaw, you will be able to see a vast collection of tangible historical artefacts that contains both objects of everyday use and works of art. In the exhibition, you can admire various items like clothing, utensils, religious artefacts, and artworks that provide insight into the diverse cultural influences that shaped Warsaw over the centuries. The Museum of Warsaw is not only a repository of historical objects but also a place to immerse yourself in the city’s rich cultural and material heritage and learn about the stories of its past inhabitants.

In the exhibition, you will also be able to learn more about Warsaw’s near-total devastation during the Second World War. We especially recommend following a special route assembled using objects related to the Warsaw Uprising. Through this special route, you will gain insight into the stories of individual people who lived through the events of 1944. You can find instructions on how to follow this route on the Museum’s website: muzeumwarszawy.pl/en/sladami1944/

Check the opening hours and plan your visit to the Museum of Warsaw: muzeumwarszawy.pl/en/visit/

ACCESSIBILITY:

Free admission to permanent and temporary exhibitions is available to people with disabilities (after presenting an ID card or disability certificate) and their accompanying guardian.

The Museum of Warsaw main seat is a historic building – a labyrinth of small rooms often accessible by stairs, thresholds or steps. The convenient entrance, accessible for wheelchairs, is located on Nowomiejska Street.

At the ticket desk you can borrow free typhlographic plans of the museum and free audio guides with audio descriptions of selected objects.

Tank explosion on Kilińskiego Street

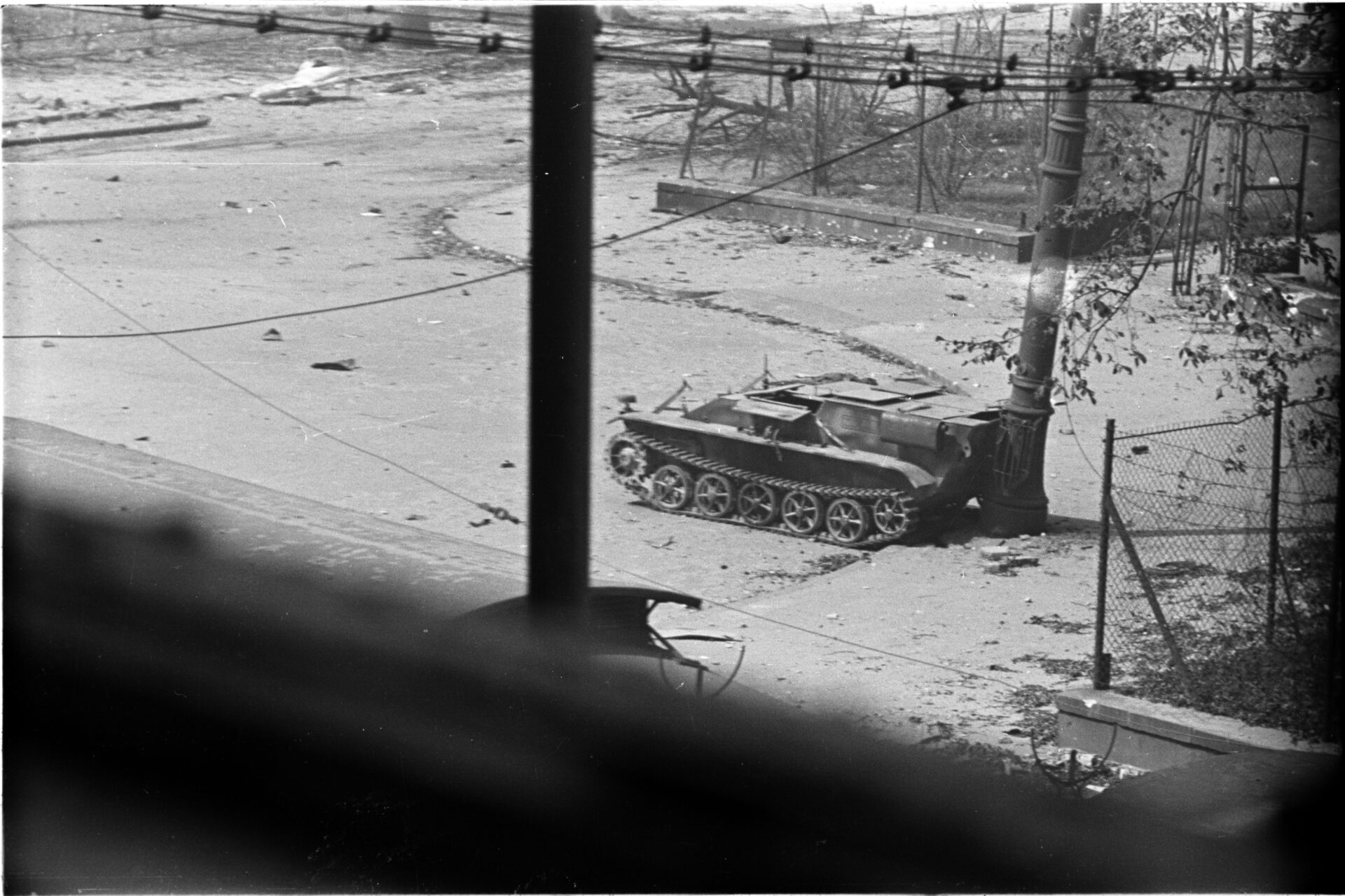

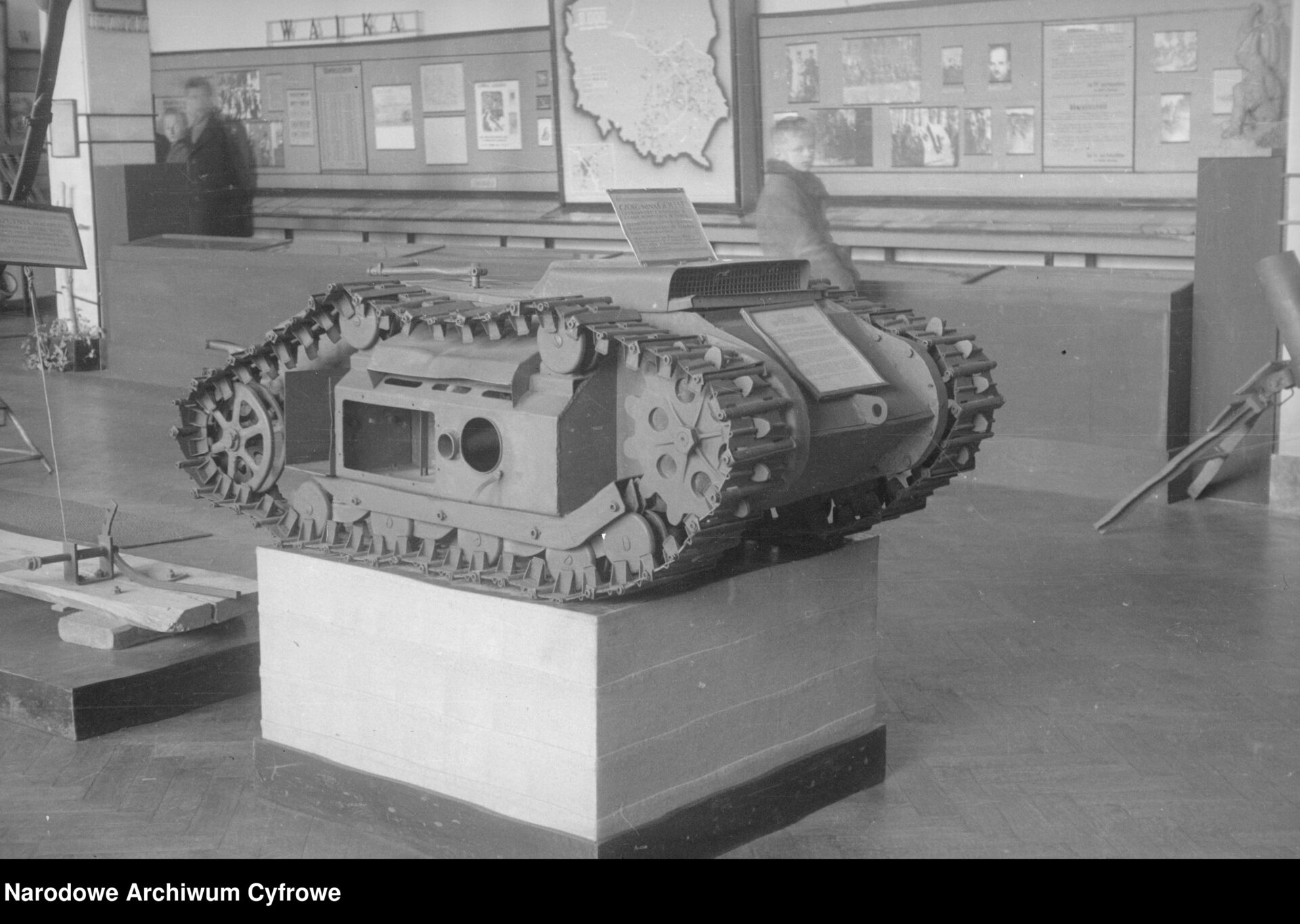

On the lawn in front of the pavilion, find a stone slab with a metal casting of a tank’s caterpillar track. This site marks one of the most tragic moments in the history of the Old Town. On August 13 1944, a group of insurgents seized a heavy, remote-controlled demolition vehicle during fighting in Castle Square. Despite initial reservations, the vehicle was taken into the residential streets of the Old Town in a triumphal parade and exploded in Kilińskiego Street. Often said to have been an act of deliberate sabotage by the German army, the explosion was most likely the unfortunate result of the insurgents’ lack of caution. It claimed at least 300 lives in one of the most horrifying events of the uprising.

The Statue of the Little Insurgent

Before you, in front of the Old Town defensive walls, stands a small monument. Known as the Statue of the Little Insurgent, this somewhat controversial memorial is dedicated to the child soldiers of the Warsaw Uprising. Children under eighteen participated in the underground resistance movement and the Uprising, mostly as messengers or carriers, but – on occasion – also as combatants. Many were members of the Gray Ranks. It was the codename for the underground paramilitary the Polish Scouting Association.

The memorial, which depicts a little boy wearing a German helmet, an oversized camouflage jacket and a machine gun, is based on a sculpture created by artist Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz in 1946. After receiving an award in a competition for artistic commemorations of the Uprising from the Association of Polish Artists, Jarnuszkiewicz’s creation started being reproduced in the form of small statuettes which circulated as popular souvenirs after the war. In the 1980s, a local scouting group successfully raised money to turn this popular symbol into a permanent memorial.

It’s important to note that, since then, the Statue of the Little Insurgent has been met with valid criticism from those who point to its glorification of children’s participation in military conflicts. On World Children’s Day in 2011, a group of local activists temporarily transformed the monument by decorating it with children’s toys: a slide, colourful balloons and an inflatable swimming pool. This artistic intervention was meant to symbolically restore the figure’s association with childhood rather than militarism, and trouble the memorial’s presence in public space.

The Heritage Interpretation Centre, Brzozowa Street 11/13

During your walk, we encourage you to visit the Heritage Interpretation Centre, a branch of the Museum of Warsaw dedicated to the history of the Old Town. The Centre offers an interactive exhibit showcasing photographs, archival films and multimedia displays focusing on the Old Town’s wartime destruction, postwar reconstruction, and recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Here, you will be able to see what this area looked like after the Second World War, the extent of damage it suffered during the conflict, and the tremendous effort of architects and ordinary people that went into rebuilding it from ruins. The displays highlight the significance of preservation efforts in maintaining the historical authenticity of the Old Town.

Check the opening hours and plan your visit to the Heritage Interpretation Centre: ciz.muzeumwarszawy.pl/en/

ACCESSIBILITY:

The Heritage Interpretation Centre is accessible for disabled visitors. Visually-impaired visitors can use typhlographics and audio guides, which are available on the first floor.

Free admission to permanent and temporary exhibitions is available to people with disabilities (after presenting an ID card or disability certificate) and their accompanying guardian.

Dziekania Street

When you reach the archway on the intersection of Kanonia and Dziekania streets, look around for a small symbol resembling an anchor, located under the arched entrance. Composed of the letters P and W – which initialised the phrase „Polska walcząca” (‘Poland in combat’) – this sign was the emblem of the underground resistance movement and the Home Army during the Nazi occupation. In this particular spot, it marks the location of a barricade built here during the Uprising. Barricades were constructed out of cobblestones, pavement slabs, pieces of damaged German vehicles, and any other available materials. They were supposed to help the insurgents defend the Old Town.

If you go into Dziekania Street, you will see another important commemorative site on the wall of St John’s Cathedral. Try to find a small nook in the cathedral’s brick wall. This opening holds a piece of an armoured transporter’s caterpillar. The plaque wrongly indicates that this object was part of a German Goliath tank used to demolish the Cathedral’s wall. Most likely, it’s a piece of the Borgward transporter that exploded on Kilińskiego Street. However, if you look carefully at the colour and arrangement of the brick on this wall, you will be able to notice where the wall of the Cathedral was breached.

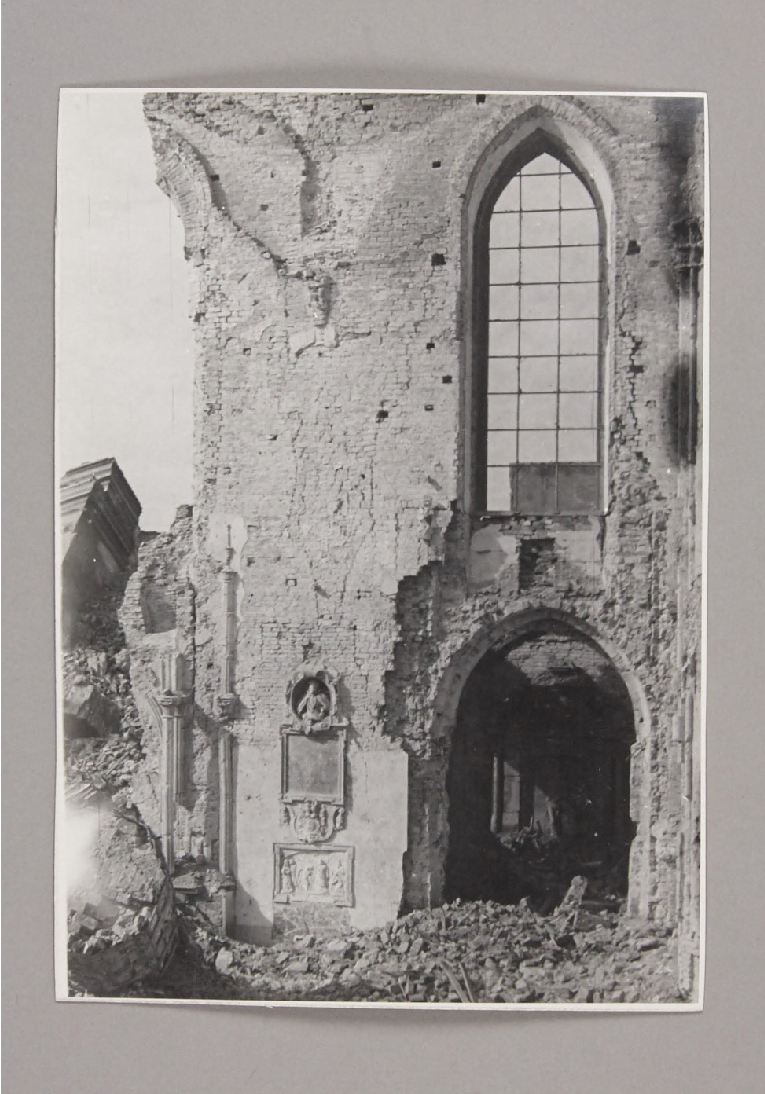

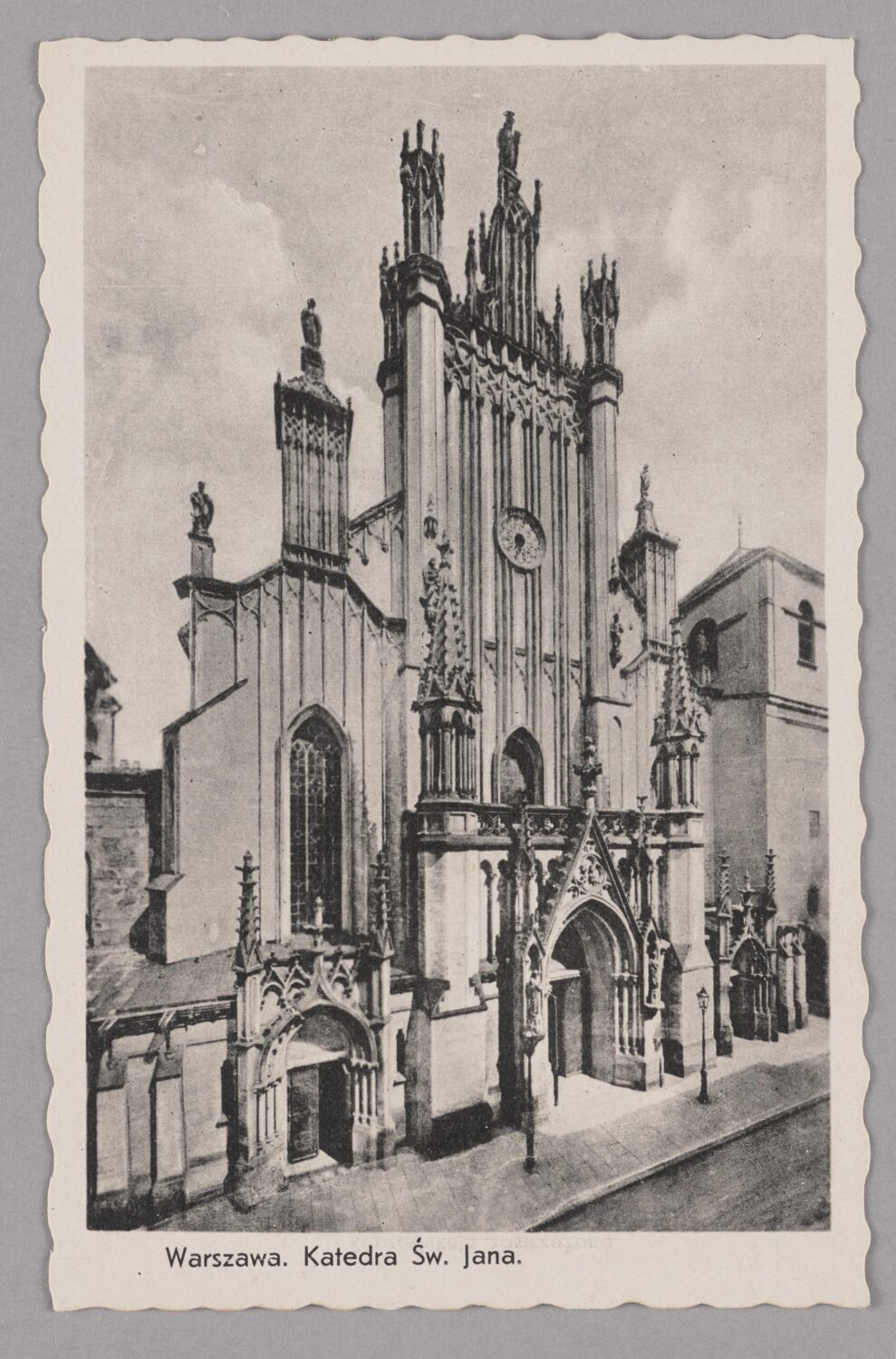

St John’s Archcathedral

St John’s Archcathedral, which is the mother church of the Catholic Archdiocese of Warsaw, has long been a symbolic site within the city. Its burial chamber holds the remains of many notable figures, including Poland’s last king, two presidents and many distinguished artists. As such, it became a target for the occupying German Army from the onset of the war, sustaining some damage already in September 1939. Then, during the Uprising, the Cathedral became the site of direct combat and was almost completely destroyed. On August 17, German artillery fire and incendiary shells set nearby houses on fire. Due to strong winds, the fire rapidly moved to the Cathedral’s main naves, presbytery and side chapel. As a result of the fire, the church’s ceiling collapsed. However, the insurgents managed to maintain their position within the Cathedral. Determined to take over this key site, the German Army used remote-controlled detonation tanks to gain access to the building. After the collapse of the Uprising, the German Destruction Commando used explosives to conclude the distruction, leaving 90% of the Cathedral in ruins.

Interestingly, the Cathedral postwar reconstruction – led by Jan Zachwatowicz – did not aim to faithfully recreate the building’s prewar neo-gothic appearance. Rather, it attempted to revive the cathedral’s presumed mediaeval form.

The Royal Castle

As you exit Świętojańska Street, you should see the Royal Castle in front of you. This site was the seat of political power for many centuries after the city’s founding, first as a stronghold of Masovian dukes and then as the official royal residence of Polish kings. Its current form reflects the style of the Swedish Vasa dynasty which ruled Poland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, the castle is almost entirely a reconstruction, having sustained catastrophic damage throughout the Second World War. Already on September 17, 1939, a shell hit the Castle during a German bombing raid on Warsaw, igniting a major fire. Even though the Nazi plan for erecting a party congress hall in its place was never realised, the Castle was nevertheless systematically destroyed in the aftermath of the Uprising. Notably, it was not rebuilt immediately after the war. The reconstruction process started only in the early 1970s, in a period when the Communist Party was increasingly using nationalism to legitimise its rule. Work on the reconstruction lasted until the late 1980s.

Sigismund’s Column

The final stop of our walk is probably already familiar to you. Sigismund’s Column, which stands in the Castle Square, is an important daily orientation point for thousands of Warsaw residents and visitors. Erected in 1644 in celebration of king Sigismund III Vasa, it was not only a personal memorial but also an expression of his dynasty’s imperial aspirations. If you take a closer look at the pedestal, you will notice bronze plates bearing Latin inscriptions. In addition to restating the Vasas’ claim to the Swedish crown, these engravings celebrate Sigismund’s victories over the Muscovites and Turks.

Most of the metal components of the column, including Sigismund’s statue, are original. However, the stone shaft of the column looks very different to its seventeenth century form, having been made in granite instead of the original red limestone. Why this transformation? The answer once again demonstrates the impact of the Uprising on the physical fabric of the Old Town. On September 2, the last day of warfare in the Old Town, the Germans shelled the column, shattering the limestone. The broken shaft still rests against the southern wall of the Royal Castle. You can approach it and look for munition marks on its surface. The King Sigismund monument itself did not suffer much damage. When it fell to the ground, only a piece of his forearm broke off. As a well-established symbol of the city, the statue was repaired after the war and set on a new granite shaft. It was unveiled on 22 July 1949.