25.07.2023 / Activities, News, The Museum of Pharmacy, Walking tour

The City of Women

The route of the walk designed by Sylwia Chutnik begins at the New Town Market Square and runs via the Barbican, Old Town Market Square and ends in Piekarska Street.

During the walk, you can find out, for example, who looked after the Benedictine Nuns Monastery, where the only Museum of Maria Skłodowska-Curie in the world is located, as well as which woman led to the construction of the bridge over the Vistula River and where the ‘witches’ were executed.

The route consists of a path in the footsteps of outstanding women residing in the Old Town area.

Duration: 1,5h

For whom: the youth and adults interested in the history of Warsaw

Accessibility: walk adapted for people with visual impairment

What to take with you on the walk?

Charged mobile phone and earphones.

There is a possibility to download and print the children’s activity sheet (PDF file) before the walk.

The pins on the map refer to the colours next to the titles of the recordings. You can open the map using Google Maps app on your phone by clicking on the rectangle in the top right corner. To listen to the recordings, you need to return to the browser and to this page.

Please listen to the introduction on the way to the first point on our map.

INTRODUCTION

We invite you for a walk in the footsteps of eminent females who once resided and worked in Warsaw. At school, we are taught dates, the chronology of royal dynasties and the course of battles. And yet, it is individual life stories and the history of a daily existence that builds our own identity, constitutes the source of culture and social rules. Even though we learn Polish history already in the primary school, we still often think of it as a necessary evil, yet another subject to pass. Meanwhile, learning about the past may turn out to be a point of departure for most intriguing research conducted according to one’s own individual key. One such key might be discovering women who lived and worked in our country, our city, or our district. It turns out that there were many of them, often very inspiring and interesting. Alas, the memory of these women did not last—they often end up in the pages of history books as somebody’s wives, mothers or assistants.

The women of Warsaw funded monasteries and public utility buildings; they designed and sculpted, they taught new generations, wrote books and looked after the sick and the poor. Where are they now? In school textbooks? En route of a traditional urban walk? Or perhaps in bulky volumes devoted to the heroic history of our motherland?

Finding even a name of some of them borders on impossible. One has to dig through hundreds of books and historical sources, like an archaeologist. Occasionally, the women are there, somewhere in a footnote of a scholarly work, listed as wives of important personalities. They hide in a black-and-white photo, often with the “N.N.” caption. In order to be protagonists of their own biographies or studies, they must have done quite a lot—so much so that their achievements simply could not be ignored. All the rest remains silent, in the shadow of a subsequent war, a change of a royal or some political event.

And yet, the women of Warsaw knew how to fight for their rights. They proved it more than once. Their lives, their determination in the pursuit of their dreams and their daily fight for identity continue to be a great inspiration for me.

Living and working in the capital city of Poland, I do sense the presence of thousands, if not millions, of grandmothers and great-grandmothers who propel the new generation to action with their steadfastness. Let us meet them during our herstoric walk titled “The City of Women”.

NEW TOWN / OLD TOWN

Can we still come across something interesting along a traditional touristic route?

For the majority of Varsovians, the Old Town is a must-see in the itinerary they draw for their cousins coming to Warsaw from other places. We try to convince them that what they see is centuries old and constitutes our heritage. Typically, tourists get intrigued upon hearing the news that 90% of this part of the city was razed to the ground after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising.

But wait! If it was razed to the ground, what are these supposedly historic buildings doing here?

It is fair to say that, thanks to the commitment of a whole team of people headed by Professor Jan Zachwatowicz, most of the key buildings were rebuilt rather precisely after the war.

At a time when the fate of, say, the Zakrzewski side of the Market Square was at stake, Professor Zachwatowicz acted shrewdly while dealing with the officials from the Warsaw Reconstruction Office. He would tell them, for example, that it was imperative to preserve the old shape of tenement buildings, as otherwise the churches would tower over the houses. The officials were quick to decide on full reconstruction. He also tried to avoid the rules and regulations of the time—if a building doesn’t have a first floor, we don’t do it, there’s no point. Zachwatowicz found a way out here, too—he had the workers lay a few bricks at night, at least for a while, so that it would be clear that there was some floor left and the construction process could begin.

Maria Zachwatowicz, Professor Jan Zachwatowicz’s wife, was an architect, too. She was responsible for, among others, reconstruction of the Sapieha Palace at 6 Zakroczymska Street. She reared two daughters: Krystyna (an actress) and Katarzyna (a singer).

We will start our walk in the New Town, by stopping at the usually empty Market Square. We will reach the Square by walking down Freta Street.

NEW TOWN MARKET SQUARE

The extensive Square is flanked on two sides by a row of tenement houses. Opposite, on the eastern frontage, stands St. Casimir’s Church. It towers over the Square. It is also distinguished by the snow-white colour of its façade. Next to it, the monastery complex of the Benedictine Nuns of the Blessed Sacrament is located. The Square is paved with grey cobblestones. Tenements’ façades feature a variety of colours, dominated by the shades of orange, red and burgundy. Most of the tenement buildings are topped with a triangular red roof.

It’s an odd place—it only comes to life during outdoor events. When the Wars Cinema was still in operation here, you could at least see groups of people waiting for a screening. Nowadays, you usually end your urban walks here and sit down in one of the several restaurants.

We walk up to the well for a moment. Back in the 19th century, it was located next to the Mostowskis Palace; at its very top, we can see the coat of arms of the New Town: a maiden with a unicorn. It doesn’t require psychoanalysis to decipher this symbol, but at least the image of the girl is rather pretty.

Originally, the Square itself was somewhat larger, and until 1818 the city hall building stood in its middle. What may now be of interest are the decorations on the façades of some of the tenement houses—for example, silhouettes of dancing couples at some kind of ball. One of the façades is adorned with a painting of the aforementioned lady with a unicorn. Above the doors of some buildings, however, are bas-reliefs showing a variety of animals: a bear, a ram and a rooster among them. However, these are not the only animals one may come across at the New Town Market Square.

Two twin sculptures depicting a bear are located here, too. The animal is standing on its rear paws, has a slightly open muzzle facing upwards and tousled hair. It is holding a coat of arms with an image of a pharaoh.

Numerous embellishments, as well as the sculptures, differ from the original. During the postwar reconstruction, for example, religious symbols were replaced by neutral animal figures or floral motifs.

Back to the topic—we are now moving towards a truly beautiful Church of St Casimir, commonly known as ‘Sakramentki’ [Nuns of the Blessed Sacrament]. It was designed by Tylman of Gameren and built between 1688 and 1693. This outstanding architect was a representative of mature Baroque’s classicising trend. The white graceful building is located on the Square’s right-hand side. It is slightly set back from the other lower buildings. It stands out among them in both colour and form.

The Church’s location and design allow us to view it from all sides. The building is symmetrical and harmonious, crowned with a light green dome. The same size front entrance, main altar and two side chapels adjoin the octagonal-shaped central section. The Church’s exterior is adorned with discreet pale yellow embellishments: pilasters, or flat pillars, as well as bas-reliefs.

The Church is also distinguished by its beautiful, even lighting. The effect is achieved thanks to the many windows located in the façade walls and also in the dome drum.

The name stems from the Benedictine Nuns of the Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. It is a closed order, and the patron saint of the female branch is St Scholastica, sister of St Benedict.

The monastery and the Church were founded by Marie Casimire Sobieska as a votive offering in thanksgiving for her husband John’s victory in the Battle of Vienna. Towards the end of the 17th century, however, before the sacred buildings were erected on this site, Wyszogród pantler Adam Kotowski lived here with his wife Maria. They occupied a building designed by Tylman of Gameren, architect responsible for the design of many of Warsaw’s churches and palaces. Marie Casimire purchased the land from the Kotowskis and brought the Benedictine Nuns Order from France.

What do the Benedictine Nuns do? They adore the Sacrament. Day and night, one of them prays in the church, separated by a glass pane from those gathered inside and from the altar.

The Church itself is small and its interior is rather ascetic. Inside, there is an impressive tombstone of Princess Marie Caroline de Bouillon, granddaughter of King John III Sobieski. It consists of several elements. It draws attention with its ingenuity and impresses with the finesse of its execution. The tombstone is the work of Lorenzo Mattiella. Designed in Rococo style, it was created in Dresden between 1745 and 1746 and is housed in the chapel, on the side wall.

The central part of the tombstone is a white marble medallion. It is decorated with a bas-relief depicting a woman facing us in profile. Her facial features are classical, her hair is pinned up high and she is wearing a richly decorated gown. The medallion, encircled by a black floral garland, is supported by sculptures of two goats. They are located on a bronze sarcophagus in the shape of a trapezoid on which a relief in white marble of a royal crown and a broken shield is visible. Sculptures have been placed on two sides of the tombstone—on the right, there is the figure of a woman. Her young body is covered with draped robes. Her entwined hands are resting on the sarcophagus, leaning her entire figure towards it. On the other side, the artist has carved the figure of a small cupid who bravely supports the sarcophagus. At his feet, there is a prince’s mitre—i.e. a particular type of crown. The whole thing is framed by a beige marble arch decorated with two sculptures of vases with burning candles. Beneath them are reliefs of skulls. The arch is linked to a black plaque placed on a pedestal—an elevation made of marble.

A broken shield placed on the epitaph symbolises the extinction of the royal line of the Sobieski family. Before her passing, Marie bequeathed her rich book collection to Andrzej Załuski, Bishop of Chełmno, who donated it to the Załuski Public Library. Alas, her name isn’t usually mentioned in the pantheon of donors.

The Benedictine Nuns Order interrupted their prayers only once—towards the end of August 1944, when the Old Town was only just fighting back during the Warsaw Uprising. At that time, the Nuns opened the basement of the church, where Warsaw residents took shelter. In his Pamiętnik z Powstania Warszawskiego [A Memoir of the Warsaw Uprising], Miron Białoszewski describes the entrance to the underground as follows:

“Into a hole. A crack. Some steps. Into something dark, damp, crowded. And this flap—was it a flap?—this entrance (descent) under the St Casimir Church? Was there something made of planks at all? And underneath it, deep down there are crowds. It’s a nest.”

Białoszewski could not take shelter there as more than a thousand people were hiding inside the well already and there was no room left. On 31 August 1944, as a result of bombing, the vault of both the temple itself and the basement collapsed. Everyone died under the rubble, including more than thirty nuns.

The first reconstruction plans were drawn up by one of the sisters, Michaela Walicka. She was the one to ensure that the damaged interior was faithfully restored. The Church was renovated a few years ago; Barbara Kubisa was one of the conservation officers. History shows that the monastery was indeed cared for by women alone.

Standing in front of the Church, we can take a few steps to the right and see the plaque informing us about a 19th-century boarding school for girls once located here. Two two Polish writers: Maria Konopnicka and Eliza Orzeszkowa attended the school. As Anna Czerwińska writes on the Women’s History Museum website:

“Eliza Orzeszkowa organised a fundraising event for the purchase of a ‘national gift’ for Konopnicka—a manor house in Żarnowiec. Throughout her life, by the way, Orzeszkowa did not stop to support Konopnicka: defending her in the press when successive Catholic thunderbolts rained down on her, supporting her financially and acting like a true friend.”

In 1886, a secret women’s organisation, the Women’s Circle of the Crown and Lithuania, was founded under the auspices of both Eliza Orzeszkowa and Maria Konopnicka.

16 FRETA STREET

Freta Street is mainly about the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum.

Maria Skłodowska-Curie. Posthumous medal, Józef Aumiller, 1934, MHW 23965, fot. A. Czechowski, I. Oleś

Maria Skłodowska was born in a tenement house at 16 Freta Street, which today houses the only museum in the world devoted entirely to her life and work.

The tenement was built in the 18th century. However, it has been rebuilt twice and its present appearance is the fruit of these reconstructions. It is a broad, three-floor building with a bright façade in broken white. It boasts seven rows of large, rectangular, white windows. In the middle is the entrance to the building, which leads through a rounded wooden door. Above the door, there is a balcony with a metal balustrade. The central part of the tenement building is topped by a tympanum, i.e. a triangular gable. It is a plain tympanum with a round window in the middle. The building is adorned with minimalist architectural decoration in the form of window frames and cornices, i.e. horizontal strips running along the entire length of the building. Its main features are simplicity, harmony and elegance.

Maria Skłodowska’s father, a mathematician and physician, ran a male gymnasium (later the building also housed a dormitory for women). He made sure his daughters received proper education—a fact less than obvious in the late 19th century.

Maria’s first chemical experiments were conducted in a lab of the Museum of Industry and Agriculture at 66 Krakowskie Przedmieście Street. However, she spent most of her life in France, where she displayed exceptional talent already during her studies.

She was the first woman in history to pass the entrance exams to the Faculty of Chemistry and Physics at the Sorbonne in Paris, and the first woman (to date) to be awarded the Nobel Prize twice (in 1903, together with her husband Pierre Curie, for research in the field of radioactivity, and the second time in 1911 for the isolation of pure radium).

She was also the first woman ever to be granted the title of Doctor of Physics, and Professor of the Sorbonne.

She is the first and the only woman to date to be interred in the Panthéon in Paris.

The beginnings of her scientific career were difficult—notorious poverty and proving that, being a woman and an immigrant from the East, she was capable of conducting research on her own. Skłodowska-Curie was distinguished by her incredible dedication to scientific work, for which she ultimately paid with her life. She died of leukaemia most likely caused by severe radiation exposure. Towards the end of her life, her hands were permanently burned by various chemical reagents. Despite this, she continued to run her lab while helping other female scientists.

Maria’s daughter, Irene, inherited her mother’s passion—she was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1935 together with her husband, Frederic Joliot-Curie.

MOSTOWA STREET

While walking towards the Barbican, it is worthwhile to stop at least for a moment in Mostowa Street which runs down, towards the river.

A wooden bridge was built over the river in the second half of the 16th century. After about 30 years, it was destroyed by an ice floe and would not have been rebuilt if it hadn’t been for Anna Jagiellonka—after the death of King Zygmunt II August, she took over the supervision of the bridge construction, financing it with her own funds.

The Queen herself was more closely associated with Kraków, but she died in Warsaw in 1596. Her body was displayed in one of the rooms of the Royal Castle, but she was buried in the Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków. During her funeral eulogy, Piotr Skarga—who dedicated his Sermons to her—highlighted the late Queen’s services to the Warsaw clergy.

Even if, officially, Warsaw was considered only the residence city of kings until 1795, people of means invested in its development. Anna Jagiellonka was one of those who sought to expand the city’s area and connect it with the territories on the other side of the Vistula River.

7 KRZYWE KOŁO STREET

We proceed towards the Barbican’s defence wall, and from there we enter Krzywe Koło Street.

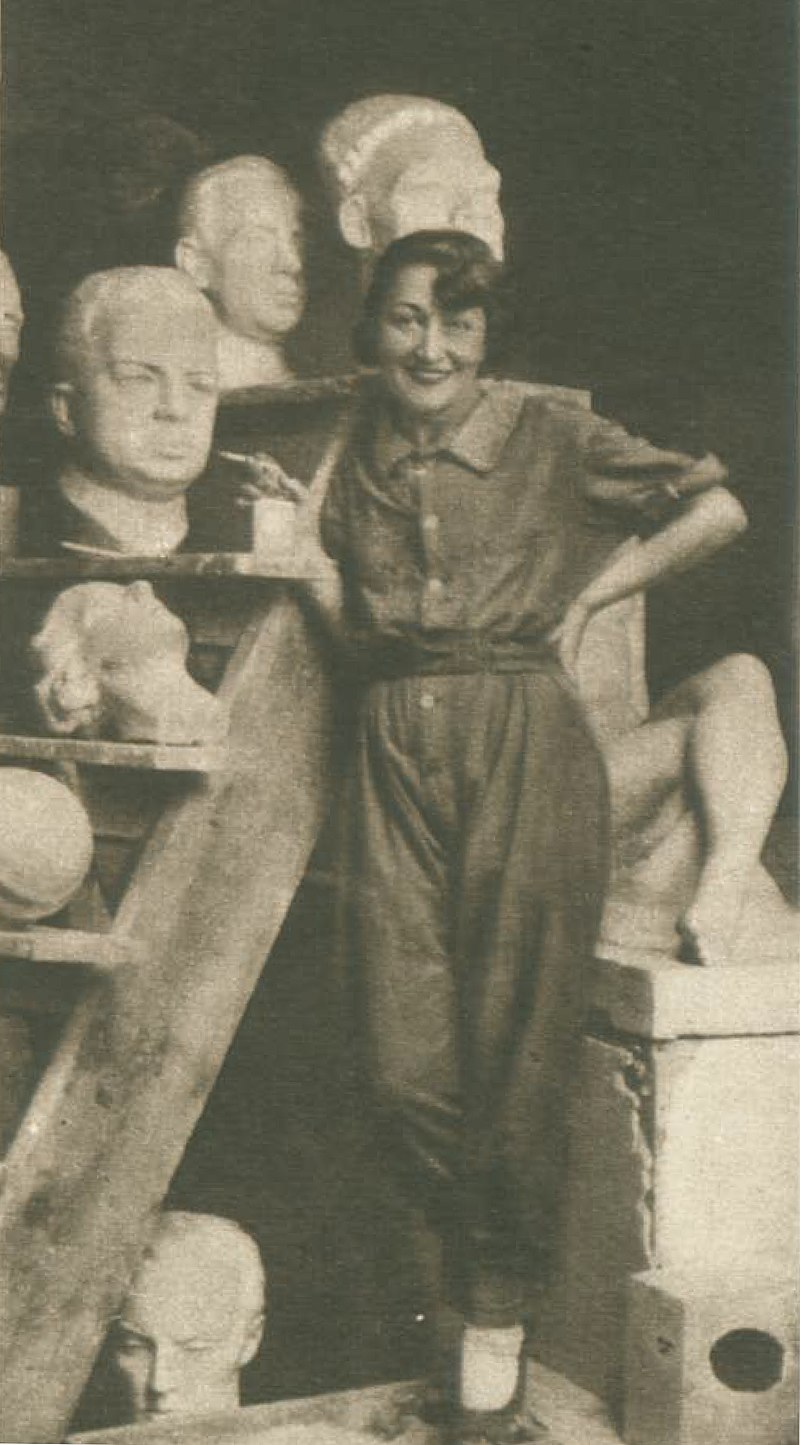

The apartment of sculptor Olga Niewska was located at number 7. The artist later moved to 7 Górskiego St, and next to 18 Bracka St where she resided until her death with her third husband, Władysław Szczekowski.

Niewska’s studio was located at 1 Zakroczymska Street. She used to invite the most distinguished individuals of the interwar period there, including Marshall Piłsudski himself. Among the women with some association to Warsaw who posed to her sculptures were: Halina Szmolcówna (primabalerina of the Grand Theatre), Mieczysława Ćwiklińska (actress), Elna Gistedt-Kiltynowiczowa (actress), Halina Hulanicka (ballet dancer), Zula Pogorzelska (actress), Nela Samotyhowa (social activist), Stanisława Walasiewicz-Olson (athlete), Wanda Zawisza- Glińska (painter) and Olga’s mother, Eugenia.

And yet, Niewska’s most significant gift to Warsaw is the magnificent sculpture titled Women in a bath which is standing in the Skaryszewski Park today.

In September 1939, her studio burnt down after an air raid. She lost most of her works. The artist died during the Second World War of complications after a surgery and was buried at the Evangelical Augsburg Cemetery on Żytnia Street, very close to the grave of writer Stefan Żeromski.

The tenement at 7 Krzywe Koło Street is a three-storey building. The dark brown window frames stand out clearly against the salmon-coloured façade. The only ornaments are the cornices—horizontal projecting mouldings—above the windows and between the floors. A brick recess stretching between the ground and first floors is an eye-catching element, as it provides a rhythmic decoration. The entrance to the building is located right below the recess, formed by a bright stone portal framing a brass door. Next to it, a red plaque informs us about the current purpose of the building, which houses the City of Warsaw Archive.

OLD TOWN MARKET SQUARE – THE MERMAID’S MONUMENT

Let us proceed towards the Old Town Market Square with Her in the middle—the symbol of Warsaw, half-female, half-fish.

Warsaw Mermaid, Konstanty Hegel, 1855, MHW 27549

The Mermaid’s monument by Konstanty Hegel was first located at the Market Square, next within the area of the ‘Syrena’ Sports Club on the Vistula, from where it was moved back to its original location in 1999. It was made in 1855, cast in the famous Minter’s studio.

Today, it sits on a pedestal surrounded by a water channel which pumps out water every few minutes with a loud slurping sound. The pedestal takes the form of a hexagonal plinth made of sandstone. On it, the Mermaid emerges from the foamy, breaking waves. Her tail is long, spirally twisted and covered with numerous scales. Her chest is bare, proudly thrust forward. She is yielding a long, sharp sword in her right hand. She raises her hand in a heroic gesture. In her left hand, she is holding a large oval shield for protection. The Mermaid’s body is harmonious, supple and taut, ready for battle. The face is calm and dignified. Her facial features are classical—prominent lips, large eyes, shapely nose. Her ponytailed hair is wavy.

It is worth adding that the Mermaid’s most famous representation is located along the Wybrzeże Kościuszkowskie Street. It is the work of eminent sculptor Ludwika Nitschowa; beautiful poet Krystyna Krahelska posed for the sculpture. The sculpture was created in a rather original studio—the hall of a disused boiler house at the Warsaw Water Filters (also known as the Lindley’s Filters, 81 Koszykowa St). President Stefan Starzyński personally commissioned the sculptor to produce a bronze monument and visited her several times while she was working on it. The original design could not be realised due to the high cost but, already in 1937, a plaster cast was sent to the Łopieński Brothers’ workshop. The full concept of the area surrounding the sculpture—an observation deck, sculptures of seagulls and fish-shaped water outflows—were never realised. Most of the previously prepared models were destroyed during the Second World War. The monument survived, slightly damaged. Krystyna Krahelska perished during the Warsaw Uprising and the Mermaid gained a new symbolic dimension.

How come a mermaid ended up as the Polish capital’s emblem? As it is usually the case, there are many versions. One is that the figure was borrowed from the Rawicz coat of arms, which shows a maiden riding a bear. According to another version, the modern image of the Mermaid is the result of many graphic changes to the original drawing depicting half-woman half-dragon, which can be found on the oldest seal of Old Warsaw dating back to 1402. The changes to the image can be traced in the permanent exhibition at the nearby Museum of Warsaw, which also houses the original statue of the Mermaid from the Warsaw’s old Town Market Square.

OLD TOWN MARKET SQUARE – ST ANNE’S TENEMENT HOUSE

Let us trace stories about women linked to the tenement buildings lining the Old Town Market Square.

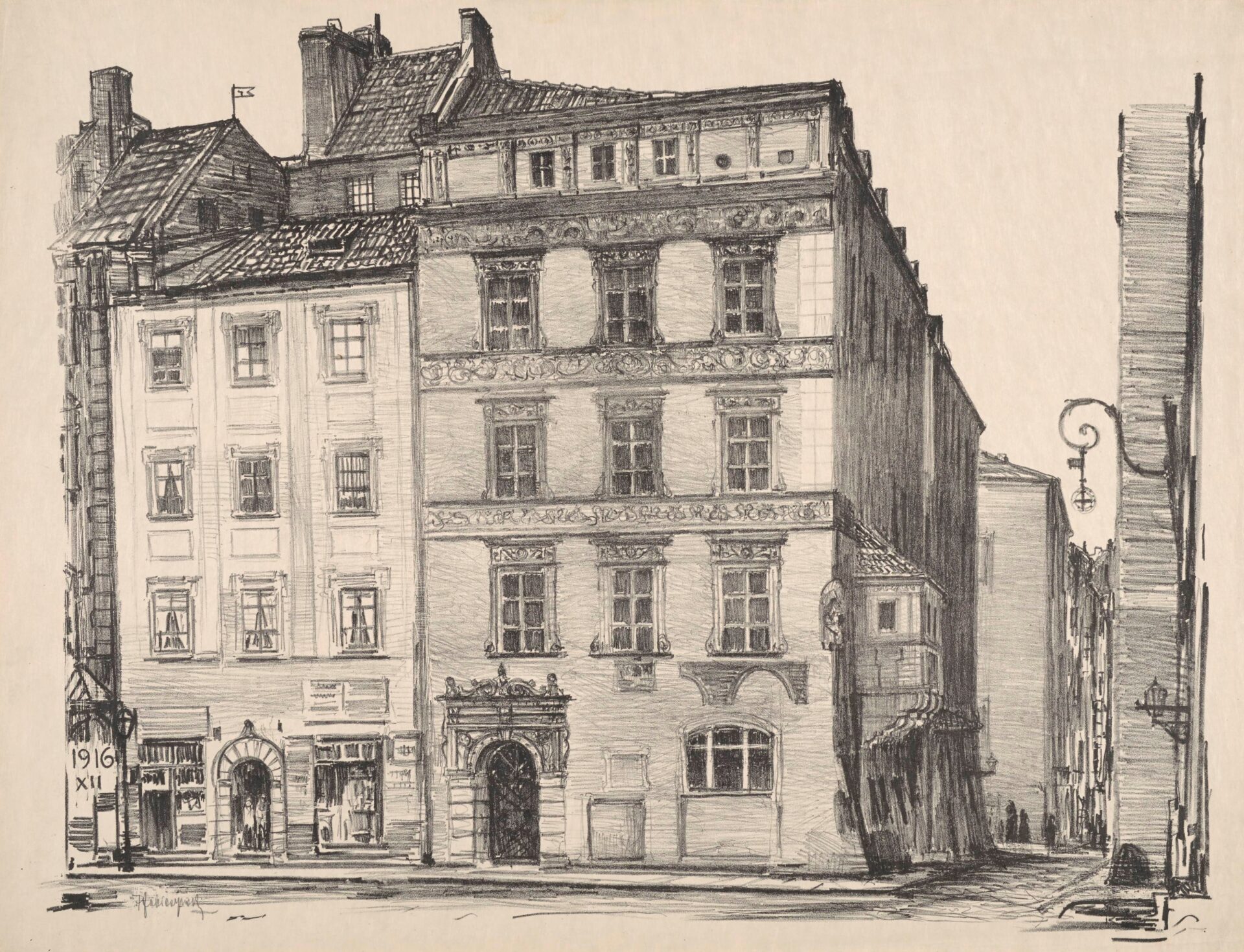

Along the Kołłątaja Side, next to the mouth of Nowomiejska Street, the house at number 31 draws our attention. It is commonly known as the St Anne’s Tenement House.

The current appearance of the building is close to that of the mid-15th century; it incorporates an element of Gothic architecture in the form of raw bricks left here and there against a white-plastered wall.

The building, also referred to as the Dukes of Mazovia tenement, boasts a fragment of a window from the time of King Władysław IV on the front façade.

However, the statue inserted in the corner of the building, depicting the Virgin and Child with St Anne is the most important element. Although small in size, the statue gives the impression of might. The figure of St Anne is stocky. She is dressed in richly draped robes that cover her entire body. She is looking into the distance. With her left hand, she is supporting Mary with long hair let loose and a small crown on her head. In her right hand, she is holding baby Jesus, plump and curly haired.

It is an authentic sculpture dating back to the first half of the 16th century. Back then, it promoted the cult of Mary the Mother which existed already in the early Christian period. In iconography, she is also shown as a little girl. She is regarded as the patron saint of married couples, mothers, widows and… sailors. The only information concerning the life of St Anne appears in apocryphal writings, i.e. those that do not belong to the canon of inspired books. We can learn from them that Anne and her husband Joachim struggled for twenty years to have an offspring, which in the Jewish culture of the time was considered a kind of divine punishment and dishonour. The despairing husband left his wife and went to a solitary place, where he fasted for forty days. Finally, God heard their prayers and gave them a daughter. Mary married Joseph at the age of 14, and St Anne came to live with them. She became a symbol of hope for infertile couples.

Why was the sculpture located right here, on this particular tenement house? Duchess Anna is said to have resided here, following the death of her brothers, the last dukes of Mazovia.

OLD TOWN MARKET SQUARE – TENEMENT HOUSE AT NO. 19

On the same side, a few dozen metres down, at number 19, the seat of the Warsaw aldermen had been located since the early 17th century.

Today, the façade of the tenement building is decorated with portraits of three maidens. They refer to a legend about the alderman’s daughters who refused to get married. They locked themselves in their rooms and wouldn’t go out. Their desperate father tried to reason with them using all the tricks he knew; finally, in utter desperation, he painted their portraits on the wall of the house. Delighted by the maidens’ beauty, young men would stop, stand under their windows and adore them. As is usually the case with patriarchal legends, the maidens gave up and politely became exemplary wives.

The portraits of the three maidens are sgraffito in the shape of red tondos—circles surrounded by a white frame. The tondos were placed between the windows of the second and third floors. They represent busts of young women who all have similar classical features. They are clad in ecru-coloured gowns and have the same light blonde hair colour. The portraits also highlight the differences between the sisters. The first one, on the left, wears her hair loose—parted in the middle in slight disarray, it falls freely onto her shoulders. She looks down and appears absent. The second sister, the one in the middle, looks the oldest. A heavy topknot, a string of pearls around her neck and a daring gaze testify to her maturity. The third maiden wears her hair in braids and a colourful floral crown. She smiles shyly at us.

OLD TOWN MARKET SQUARE – TENEMENT HOUSE NO. 13

Let us proceed further towards Zakrzewskiego Street, where a painting by Zofia Stryjeńska née Lubańska can be found on the building at no. 13.

The painter hailed from Kraków; she was fascinated by Polish folklore whose colours and patterns inspired her in her work on graphics, scenography and illustrations.

Stryjeńska was one of the most well-known female artists of the interwar period, and a source of numerous scandals. Talented and hard-working, she distinguished herself from among other artists with the originality of her work. Pretending to be a man, she studied painting in France for a year. She kept the name of her first husband, Karol Stryjeński, an architect associated with Zakopane. They had three children. The husband became famous for locking her up at a psychiatric ward twice, both times against her will. The incidents caused a rift among their circles of friends, both in Warsaw and in Zakopane, and were widely and eagerly commented on. Stryjeńska did suffer from bouts of depression, but it did not affect her work in any significant way.

After the divorce, she moved to Warsaw where she married actor Artur Socha in 1929. She spent the wartime in Kraków. After the war, she emigrated to Switzerland with her children. She died there in 1963.

The polychrome painting on the façade of the Old Town tenement house is characteristic of her work and dates back to 1928. These are two large rectangular paintings, very much alike. They depict two female figures holding jugs of water which spills out of them. The paintings fill the space between the windows at first- and second-floor level. They are similar in size to the windows between which they are located. They are polychromes, i.e. multi-coloured paintings decorating the walls. The girls are depicted in motion. They step lightly and gracefully—one towards the left, the other towards the right. Each holds one hand on her hip; the other hand supports a jug. A stream of water is flowing out of the tilted jug. The women depicted by Stryjeńska boast full curvy figures. They have long hair braided into two pigtails. They are wearing loose and airy clothes of vivid and saturated colours—tops with wide sleeves and long skirts under which their legs are delicately outlined. They are barefoot. There are large laurel wreaths on their heads, which resemble halos. The girls are depicted against golden background but they fill the polychrome space almost in its entirety.

The artist created colourful compositions full of dynamics and movement. In Girls with Jugs the dynamics is conveyed by the girls’ airy, wavy clothes, the flowing water and the floppy braids. At the same time, Stryjeńska’s artworks were very decorative. She achieved the sense of rhythm by clearly marking out the contours and painting large areas with a single colour. This can be seen in the girls’ clothing and the gold background, which gives the whole representation a decorative quality. Girls with Jugs is sometimes interpreted as a representation referring to Wet Monday [Easter Monday] and the tradition of pouring buckets of water on one another. It depicts two female figures holding jugs of water spilling out of them.

It should be noted that before the war Stryjeńska designed a figural frieze devoted to Old Poland motifs in one of the tenement buildings on Kanon Street. In Warsaw, there is one more surviving work by this artist, on Madalińskiego Street, the corner of Puławska Street.

2 BRZOZOWA STREET

Let us leave the Market Square for a moment and let’s walk down Celna Street to Brzozowa Street. Here is where Pola Gojawiczyńska, a through-and-through Warsaw writer, used to live.

Author of the novel titled Dziewczęta z Nowolipek [Girls from Nowolipki] used her own experiences and reminiscences to describe the childhood and youth of a few females, residents of the Nowolipki quarter. The novel has been adapted to the screen three times.

In her writing, Pola Gojawiczyńska focused on the life of impoverished women who, in their search for happiness, faced many challenges. The motif of relations between the women, characterised by the idea of ‘sisterhood’—namely being there for one another and deep emotional ties—recurs in her prose.

The other novels by Gojawiczyńska are Ziemia Elżbiety [Elisabeth’s Land], Rajska Jabłoń [Paradise Apple Tree] or autobiographical Krata [The Grid] in which she describes her stay at the Pawiak Prison during the German occupation. Before the war, Gojawiczyńska was supported by Zofia Nałkowska, who tried to help her younger and poorer colleague win a scholarship. The two writers spent the first few weeks after the Second World War had broken out wandering together.

Next to the house where Pola used to live, there is Gnojna Mount [Muck Mount] created by throwing out rubbish and excrements from the city—the practice banned as late as 18th century. After the dumping site had been liquidated, the embankment was covered with soil. Today, overgrown with greenery, the Muck Mount serves the role of an observation deck. It offers a view of the Vistula River and across the river to the Praga district.

The panorama of the right bank of Vistula is dominated by the National Stadium building and the two towers of the gothic St Florian Church. Benches have been installed on the viewing terrace and, since last summer, lovers have been hanging colourful padlocks on the balustrade as a sign of their love. There is also a bronze statue of a Strongman by Stanislaw Czarnowski.

The remnants of the city gate known as Gnojna Gate [Muck Gate] have survived next to the path leading to the observation deck. The red-brick Gate was built towards the end of the 14th century. Its surviving fragment is adjacent to a tenement house on Celna Street. By touching the brick wall, we can feel the marks left by bullets during World War Two. It is worthwhile to stop here, have a rest and enjoy the view of the river.

ST JOHN ARCHCATHEDRAL

Having left the Muck Mount, we will proceed along Dawna Street towards St John Archcathedral. On its door, we can trace the process of changes to the image of the Warsaw Mermaid.

The double door is massive and black, decorated with images carved in copper sheet metal. Thanks to this, they are convex and we can discover what the images represent as if they were a tactile graphics, by touch. In the middle, the most important events in the history of the church are depicted. They are placed in rectangular frames, called quatrefoils.

They quatrefoils are framed by the aforementioned images of mermaids alternating with representations of the Polish eagle. A total of eight mermaids are presented. Each is different, but all have a naked torso and hold a shield and sword in their hands.

Among the various images, we find the classic representation of the Mermaid. She is presented in the form of half fish, half woman. She is thrusting her chest proudly. From her naked torso grows a long up-turned tail covered with scales. The cathedral door decoration also contains earlier images, on which the Mermaid resembles a scary monster. On some, she is represented as a male figure. Instead of a tail, she has lizard-like paws or pointed wings like a dragon.

Some of the images are astounding, and reminiscent of another well-known legend—that of the Basilisk. Suffice it to say, the seemingly simple combination of a fish and a naked woman has continued to inspire artists to this day.

31/33 PIWNA STREET

We walk towards Piwna Street. Here, at number 31/33, the Museum of Pharmacy is located. It is named after Antonina Leśniewska, a medicine graduate who opened the ‘First Female Drugstore’ in St Petersburg.

It was the first pharmacy in the world to employ women only. It is also worth noting that the rules binding there were most progressive for their time—a seven-hour working day and a double shift. Pharmaceutical courses were organised for women.

After Poland had regained its independence, Leśniewska opened a pharmacy at 72 Marszałkowska Street. She got engaged in the struggle for women’s rights. In 1908, her book titled Nowa dziedzina pracy kobiet [New Area of Work for Women] was published in Warsaw by the Library for Equal Rights for Women. Antonina was also active in the Aid for War Victims Society, and herself founded the Emergency Aid for Polish Women Society in St Petersburg.

Initially, the Museum of Pharmacy was located on Skierniewicka Street. Today, it is part of the History Museum and its permanent exposition consists of original pharmacy equipment and numerous objects from the pharmaceutical field.

The entrance to the Museum leads through a door framed by an arched stone portal. The inscription on it reads: ANNO 1776, thus marking the date the building was constructed. A brass plaque and a black metal signboard inform us that the building houses the Museum of Pharmacy. The signboard depicts a Mermaid holding a golden serpent in her hand. The Mermaid is encircled by a coat of arms topped with a golden crown. Above it we see the inscription: Museum of Pharmacy. The signboard boasts a fine art form and original lettering. It has been installed just above the entrance, perpendicular to the building. It is a so-called semaphore signboard, a typical decorative element in the Old Town of Warsaw.

20 PIEKARSKA STREET

From Piwna Street, we turn into Piekarska Street where, back in the 16th century, tortures of the town citizens were held at the very spot of today’s shoemaker Jan Kiliński statue.

It was here that famous Piekarski was punished for an assault on King Sigismund III Vasa. Right here, thieves as well as many women tested for being witches were incarcerated in cages. The accusations were vague, but the eagerness to punish was fierce.

Nearby, at the site where the congregation of the Sisters of Elizabeth building later stood, the hangman used to reside. It was a rather disagreeable profession, but not only was it related to the income from brothels, but it could also be inherited.

Accusations of witchcraft became one of the most drastic examples of misogyny. The pretext was not only a suspicion of poisoning (such was the fate of the sister of the last dukes of Mazovia, for example), but even casting a spell or practice of ‘witchcraft’ in general.

Let us not go into details as to what the trials (or rather tortures) were like. There is also a theory that mass accusations of witchcraft made to midwives and herbalists were the revenge of medical doctors eager to get rid of the competition. To be sure, the attitude of the Catholic Church which supported these undignified trials is of vital importance here.

The first Polish ‘witch’ was burnt at a stake in Waliszew near Poznań in 1511. The trials became widespread in the early 17th century. Capital punishment for alleged ‘witchcraft’ was officially abolished in 1776.

Right next to the torture square commonly known as ‘Piekiełko’ [Little Hell] we will find a stone indicating the location of writer Maria Konopnicka’s house. This outstanding 19th-century poet, author of novellas and an insightful critic of romantic poetry was one of the first women to be able to support herself and her children from writing. She fell into oblivion, put aside in a boring ‘compulsory reading’ school canon, and yet she was a truly interesting persona in the history of Polish literature. She did not strive to find her own language—instead, she reconstructed the cultural canon with its Antiquity-related motifs, folk elements and references to Romanticism. Her novellas are characterized by exceptional drama occurring in the seemingly ordinary lives of her protagonists. Konopnicka was also a social activist, engaged in, for example, aid to the 1906 prisoners at the Citadel and their families.

Our walk could continue for much longer. We encourage you all to explore the city and take your own tours.

Co-financed from the funds of the Museum of Polish History in Warsaw, as part of the ‘Patriotism of Tomorrow’ programme.