20.06.2023 / Activities, News, Walking tour

The Secrets of the Barbican and the City Walls

Discover Warsaw city walls with us! We invite you to a special walk along the Old Town fortifications.

Do you know how old Warsaw city walls are, and which fragments are original? Have you ever wondered how did the city defend itself against enemy attacks in the olden days? In what way did pre-war tenement houses salvaged the medieval city walls?

Walking along the route we have mapped out, you will find answers to all these questions and will get acquainted with the most interesting titbits about Warsaw fortifications.

The route runs along the fortifications.

Duration: 1,5h

For whom: youth and adults interested in the history of Warsaw

The pins on the map refer to the colours next to the titles of the recordings. You can open the map using GoogleMaps app on your phone and clicking on the rectangle in the right top corner. To listen to the recordings, you need to return to the browser and to this page.

INTRODUCTION

We start near the observation deck at the corner of Brzozowa and Celna Streets.

Warsaw and its city walls boast a unique history. Despite an enormous wartime damage of the historic city centre in the wake of the Warsaw Uprising, the defensive walls are among the last vestiges of the medieval period that survived in a relatively good condition. There are many towns in Poland, some much older than Warsaw, where the walls have not survived. That is why we can refer to Warsaw as a special case.

In the medieval period, not all Polish town had fortifications. Their existence was a great distinction to the residents, as it undoubtedly increased their sense of security. During the reign of the last kings of the Piast dynasty in Poland, the largest number of towns surrounded by fortifications was in the Małopolska region [Lesser Poland]. There were even more such towns in Silesia, Pomerania and Prussia, but these territories were not within the Polish borders at that time. In Mazowsze [Mazovia], with the exception of Płock, Warsaw was the only town encircled by fortifications.

Due to the enormous cost of construction, erecting defensive walls took decades—fortifications were built gradually, each section being completed one at a time.

THE BEGINNIGS OF WARSAW FORTIFICATIONS

The beginning of the construction of Warsaw fortifications and the first references to them are connected with the time soon after the town was founded, i.e. at the beginning of the 14th century.

The costly undertaking was most likely started already by Bolesław II, Duke of Mazovia, the founder of Warsaw, and was extended and modernised by his successors with the participation of the residents.

Initially, the fortifications were mere embankments erected using timber and soil. The fortifications of Warsaw are mentioned in the context of a planned court case between the Polish state and the Teutonic Knights. Encircling the Mazovian town with fortifications was perceived as a great asset for securing this event.

Already from the 14th century, the construction of the first ring of defensive walls, which included two gates, began on the western and northern side of the town. The wall also boasted several flanking towers built on a rectangular plan, spaced every few dozen metres from each other.

THE ZWINGER

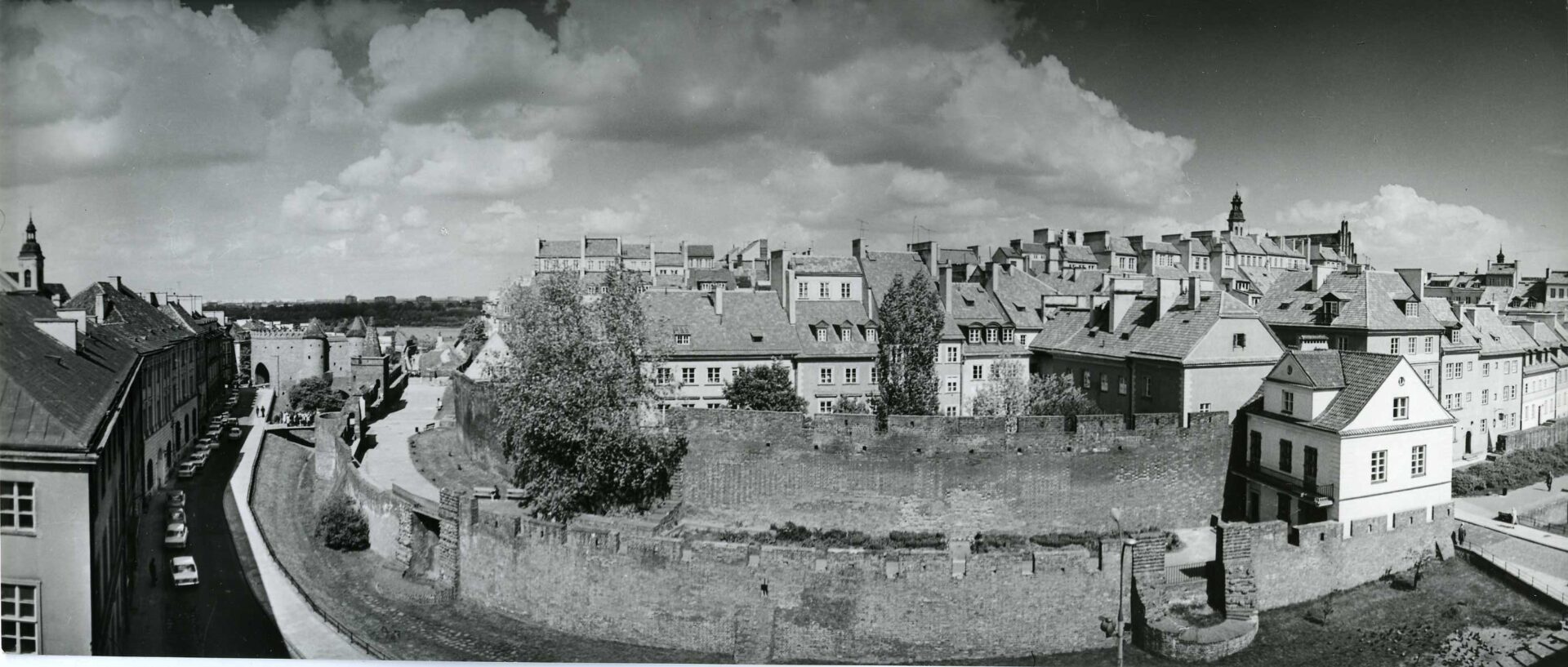

In the mid-15th century, the construction of the second, outer ring of the walls began. It was removed from the first ring by over a dozen metres. The outer circuit also featured defensive semi-circular towers extending beyond the line of the wall. The area between the first and second rings formed the ‘outer courtyard’ space, commonly referred to as the Zwinger.

From the west and the north, Warsaw fortifications were surrounded by a moat, fed by water from the stream of the small Dunaj river. It was further encircled by a road called Zawalna. Today, Podwale Street runs there. The walls with which Old Warsaw and the castle were surrounded covered an area of more than 8 hectares. Their total length was over one kilometre.

In the 17th century, the town of Warsaw could be entered through one of three gates: from the north—Nowomiejska gate, from the south—Krakowska gate and from the west—Poboczna gate, built later, at the beginning of the 17th century. On the side of the Vistula Escarpment, there were also two smaller gates through which one could get to the river.

LIFE IN THE SHADOW OF THE DEFENSIVE WALLS

Being protected by fortified walls brought not only benefits for the burghers, but also obligations and large expenses. Varsovians were obliged to serve as guards on the walls and also to carry out all the necessary repairs to the masonry fortifications.

With time, due to limited and in most part occupied space for building development, Warsaw residents were granted permission from the municipal authorities to use the walls and the Zwinger area. New buildings sprang up there, thus weakening the defensive properties of the fortifications. In the 18th century, in light of absence of any direct threats to Warsaw, the defensive walls ceased to be useful. Partially demolished, but in many places enclosed by tenement houses, they have survived to the present day. The situation was different with the gates in the walls that led to the town. They were almost completely demolished at the beginning of the 19th century—what survived was one of the Barbican walls, hidden within the walls of a tenement house.

The walk will set off from the eastern section of Warsaw fortifications, from the side of the Vistula Escarpment. We will head to the spot where Celna Street intersects with Brzozowa Street. We will find ourselves in the one-time location of Gnojna [Muck] Gate, sometimes referred to as Furta Gnojna [furta is yet another Polish word for ‘gate’].

THE GNOJNA GATE [MUCK GATE]

It was used by all those who wanted to get to the municipal dumping ground called Muck Mount [Gnojna Góra]. This involved being exposed to rather unpleasant circumstances and the need to cover one’s nose because of the foul smell coming from the nearby dumping ground. It was located on what is now the observation deck.

The gate’s volume extended beyond the line of the defensive wall whose construction began here in the late 1470s. This was made possible by an agreement made at the time between Prince Janusz the Elder, a true benefactor and protector of the town, and the Warsaw burghers. For a period of a dozen years, he exempted them from all taxes and gave them additional income so that they could build a defensive wall from the side of the Vistula River. On the river side, unlike elsewhere in Warsaw, it was decided to build a single line of fortifications. The river itself and its steep embankment further protected the town from the enemy.

The remains of the fortifications can be seen in the wall of the building at 5 Brzozowa Street. The Gnojna Gate, demolished in the 1830s, used to stand next to it. In the first half of the 16th century, the wealthy and influential Burbach family, granted the permission by the municipal authorities, based the structure of a building they were erecting on a fragment of the fortification wall. Other owners of plots along Brzozowa Street also used the fortifications as an element of the structure of their houses. As a result, a large part of the town’s eastern defensive wall along the side of Vistula was ‘incorporated’, so to speak, into residential buildings. This becomes clearly visible while entering the Heritage Interpretation Centre on Brzozowa Street, where a fragment of the city wall’s foundation is uncovered and protected in the lower ground floor.

Walking down Brzozowa Street along the wall, we proceed further to the Stone Steps, a narrow route to the Market Square. It was here that another passage in the section of fortifications from the side of Vistula was once situated. The passage doesn’t exist anymore.

RYBACKA GATE [FISHERMEN’S GATE, aka WHITE GATE]

The gate was called Rybacka [Fishermen’s] at least from the end of the 16th century. It was through this passage in the defensive wall that Warsaw fishermen would go to the river to later re-enter the city with the fish they caught.

In the early days of the fortifications there was only an opening in the wall or in the tower through which pedestrians could get to the Vistula River. This was an important and frequented passage, as the life of Warsaw was closely linked to the river, flowing much closer to the city than today.

Very soon a need arose to extend the gateway. It was indeed rebuilt approximately in the mid-16th century, after one of Warsaw’s burghers, Filip Szlichting, pledged to supply bricks and reconstruct the hitherto narrow passage into the form of a tower in the wall. At that time, the residents had to pay rent for crossing it.

Towards the end of the 17th century, the tower with the gate was plastered—from then on it was referred to as white due to its colour. Had we had the opportunity to find ourselves under the tower at that time, looking up we would have noticed a rectangular building at the bottom turning into a polygonal tower as it stretched upwards. We can also see this on the first 16th-century panoramas of Warsaw, taken from the side of the river. The tower housed the town prison. The building’s poor technical condition which posed a threat to the lives of passers-by prompted the municipal authorities to repair the gatehouse in 1786. As a result, it continued to serve the residents for several more decades.

THE MARSZAŁKOWSKA TOWER [MARSHAL TOWER]

Taking the stone steps up to Krzywe Koło Street, we turn right, heading straight for the gate connecting the two tenement houses. Having passed it, we turn right and find ourselves at the spot where the high watchtower of the inner defence wall used to stand. It was constructed approximately in the mid-14th century, when the eastern section of the walls, from the Vistula side, was being erected. Due to its shape, in the 15th century it was called the Round Tower. Later on, it was called the Broad Tower, due to its slightly larger size than the other towers—its diameter was as much as 8 metres.

In the first decades of the 17th century, when the Marshal’s authority grew in the city, the name stemming from the Tower’s chief trustee, an important royal official, the Grand Crown Marshal, was adopted.

The Tower’s location on a protruding promontory in the north-eastern corner of the town was of considerable importance. As an elevation point (it was 25 metres high), it served as a watchtower with an excellent view. When Warsaw was threatened, it was a vital point of resistance. The Tower’s lower storey consisted of a stone plinth, while the upper part was built of brick. However, for the longest time the building was used as a prison. Run by the Grand Crown Marshal, it was in operation there from the 16th till the end of the 18th century. In 1769, on Marshal Stanisław Lubomirski commission, the annex with the staircase, located on the side of the Zwinger, was renovated. However, the old walls of the tower were already badly cracked.

Noblemen sentenced to tower prison usually served their punishment here. In the basement of the tower, where a gift shop is located today, the convicts suffered the consequences of their wrongdoings.

Prior to 1810, the Marshal Tower ceased to be used as a prison—it was sold and soon demolished. Only the lower (plinth) storey survived and underwent conservation in 1950. In the postwar Old Town reconstruction project, the restoration of the Marshal Tower was considered, but this idea was eventually abandoned. Instead of the former staircase in the annex on the side of the outer ring of walls, a new reinforced concrete stairs were installed, leading to the Zwinger. In 1972, a statue of the Mermaid—originally standing in the Old Town Market Square—was erected in place of the tower.

From the spot where the Marshal Tower used to rise, we will go down the steps to the Zwinger area. Next, it is worth descending further, beyond the outer rampart. If you find it difficult to descend the steps, you can continue your walk via an alternative passage, walking away from the Marshal Tower towards the Barbican.

ST LAZARUS HOSPITAL

Below the Marshal Gate, from the north, St Lazarus Hospital was located. The building itself was not a part of the city fortification system, and yet it stood adjacent to the defensive wall.

Close vicinity to Marshal Tower makes it worthwhile to say a few words about the hospital and to look from its former location at the fortifications from the north side.

The hospital’s exact location and architectural shape are known from Zygmunt Vogel’s drawing from 1785. However, the hospital was founded at a different location. It was founded at the end of the 16th century in the New Town by members of the Brotherhood of St Lazarus’ Mercy. It was not a typical hospital as we know it today. Rather, it was a care facility (a shelter), combined with a hospital for the sick. It was distinguished by the fact that it had an infirmary ward, intended for people suffering from venereal diseases and “scabies”. In the late 18th century the hospital building housed a school for military surgeons.

The person who exerted an influence on the hospital’s operation and achievements was Walenty Gagatkiewicz, court physician to King Stanisław August. It was his idea to open a surgical school next to the hospital at the end of the 18th century.

Today, neither the St Lazarus Hospital nor the townhouses that were later erected in its location are still standing. After the war, their reconstruction was deliberately abandoned so as not to obscure elements of the Old Town fortifications. As a result, today we can admire the original—in large part—walls supported from this side by buttresses. This is a structural element of the building, requisite to protect the walls from collapsing. They were often used to support high walls, especially on uneven, sloping ground.

In addition to the buttresses, we can see the crenellations here. This is the upper part of the defensive wall with intentionally left gaps, from behind which it was possible to shoot at the enemy and at the same time to protect oneself from gunfire. In the crenellations, there were also shooting holes for the defenders of the town.

Just below the crenellations, to the left of the third slope counting from the Barbican, we can see a lighter colour of the former mortar. These are traces of original plaster fragments with remnants of decoration. In the past, much of the Old Town walls were adorned with colourful decorations.

THE BARBICAN

We shall now turn towards the Barbican, an elongated tower with turrets, constructed on a Gothic bridge. Let us look at it from below, from the level of the former moat, and next let’s walk up to enter the building. The defensive structure with its ornate attic is merely one of three elements that make up the former New Town Gate. It was erected in 1548, designed by the Italian builder John Baptist of Venice.

Warsaw’s Barbican is one of the few surviving buildings of its kind in Poland. It was also part of one of the two most important city gates, located on opposite sides of Warsaw. Let’s go inside the Barbican. In its narrow corridors, we might feel for a moment as if we were defenders of the city.

The entrance to the tower is inside, marked by a plaque. Let us climb the stairs to the first level. The exhibition on the “discovery” of the Barbican and the Old Town fortification walls as a monument begins here. Conservation work on the northern section of the fortifications began before the Second World War. The tenement house standing on part of the Barbican was destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising. That is why a more complete reconstruction became possible only after the war had ended. On the walls, there are illustrations showing the process of restoring the Barbican and the fortification walls as parts of the Old Town. On the glass of the first level window there is a graphic depicting the Marshal Tower incorporated into the ramparts. If we look straight ahead, we will see the place where a tall watchtower stood two hundred years ago.

We take the stairs to the next level and head to the right. We now follow the inner circuit of the Barbican. To the right and left are a series of small circular windows that in the past served as firing holes. It was from here that the defenders of the city could direct their fire at invaders trying to conquer the walls of Old Warsaw.

In the recesses of the Barbican’s circuit, there are a number of mock-ups presenting the former appearance of the various city gates in different historical periods: from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. Taking a closer look at them will give you an idea of what the various now-non-existent city gates, which we will discuss during the walk, used to look like.

We leave the Barbican’s interior. Outside, in the passage of the former gate, you can buy painted views and commemorative wooden sculptures. In the 1960s, independent artists used the Barbican walls for holding exhibitions and selling their artworks there. There was also a foundation called Artbarbakan, which brought together artists who exhibited works in the proximity of the city walls.

Pass through the pointed arch gate of the Barbican towards the former northern suburb. At this point, the entrance to the city was protected by an iron drop-down lattice (the so-called portcullis) and a drawbridge lowered on a chain. A little further on, by the steps to the Church of the Holy Spirit, rose part of the third New Town [Nowomiejska] Gate, which guarded the entrance to the city with double-sided wooden gates. Let us go down Podwale Street and take a look at another tower in the wall.

THE PROCHOWA [GUNPOWDER] TOWER

The tower adjacent to the nearby Barbican has a cone-shaped brick top. Like most such elements of the outer fortifications, it is semi-circular at the base. It is clearly visible from Podwale Street.

Let us take a closer look at it and then let us go down to the area of the former moat.

Erected in the 15th century, during the construction of the northern section of the outer wall, the Prochowa Tower was a very important element of this part of fortifications. Its former function is indicated by its name—in the 17th century and until the mid-18th century the Tower was the main place for storing and obtaining gunpowder.

There is an interesting story related to this place. In 1628, when Warsaw feared an invasion from the Swedish king Gustav II Adolf, the Warsaw Starost Stefan Grzybowski came to the city to check the how prepared it was for defence. Together with the Mayor of Warsaw, Stanisław Baryczka, and several others, they entered the Tower where gunpowder and cannonballs were collected. When they climbed to the first floor, the entire storey collapsed, along with the people gathered there. No one was hurt, but the incident made such an impression on people that the story was recorded in the municipal registry books.

The Tower was promptly reconstructed and over the following decades it continued to gain in importance. During this time, there were several dangerous gunpowder explosions across the town. In order to prevent further tragedies, the municipal council decided that residents who kept gunpowder in their dwellings and who sold it to others were obliged to transfer it to the Gunpowder Tower.

When the collection of gunpowder in the Tower stopped in the mid-18th century, the building was no longer needed and was demolished almost to the level of the foundations. In its place, at the site of what used to be a moat, another building was erected. In 1870, workers came across the remains of the former Tower while preparing the site for yet another development.

THE TOWER WITH A MONUMENT TO THE LITTLE INSURGENT

Let us continue along the paved Zwinger between the city walls, all the way to the exit of Kilińskiego Street, which is on our right. On the left, in the outer defensive wall, we can see an outline of the bottom part of the semi-circular tower. Only its foundations have survived.

Restoration work carried out between 1958 and 1963 confirmed the location of the ruined tower by reconstructing a section of its wall. In 1983, a sculpture of a small insurgent was placed in the middle of the tower, according to Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz.

The sculpture depicts the figure of a several-year-old boy with an oversized German helmet with an eagle, a red and white armband and a rifle slung over his shoulder. It commemorates the youngest soldiers who fought in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. It was erected here thanks to the initiative and fundraiser of scouts from the Heroes of Warsaw Regional Banner of the Polish Scouting Association. At the back of the tower, next to the sculpture, a commemorative plaque has also been mounted, reminding the public of the Scouts’ initiative.

The conservation method implemented before the war and continued during the postwar reconstruction of the fortifications is curious. The conservation officers used black mortar to mark authentic medieval wall fragments in the Barbican wall and in the walls of the selected sections of the fortification. That is how the original wall was distinguished from the reconstructed one. In the course of our walk, you will notice this without too much trouble in various sections of the fortification.

It was also important for the architects and conservation officers to reconstruct the walls to their original height only in certain sections. Thus, we can now enjoy a splendid view of the Old Town building development from Podwale Street. The towers and elements of the fortifications whose former appearance remained unknown were not reconstructed, either—for example the tower where the sculpture of the Little Insurgent stands today. Nor was a decision made to reconstruct some elements of the fortifications, such as the Marshal Tower or the Krakow Gate, whose former appearance was better known.

THE POBOCZNA [SIDE] GATE

Walking along Podwale Street, we approach Wąski Dunaj Street which runs off from the Market Square. At the turn of the 17th century, a new city gate was erected here. If we ignore the gates of lesser importance—situated on the side of Vistula River—it was the third entrance to the city, after Krakowska and New Town [Nowomiejska] Gates. Before its construction began, one of the defence towers, built during the construction of the fortifications in the mid-14th century, was located here in the line of the inner circuit of the defence wall.

The second half of the 16th century saw rapid development of the city. The Sejm held its sessions here, and soon Warsaw became the seat of a royal residence. A lot of people flocked to the new centre of the state. Many decided to stay here permanently. More houses were built in the suburbs. The need for a faster access to the town necessitated the construction of an additional gate in the western section of the wall. That is why the municipal authorities decided to cut an opening in the outer wall and to rebuild the former flanking tower. Some of its walls were used to construct a new gate. This is how it was called by the townspeople from the early 17th century. Some people referred to it as a side gate because it was not located on the main tract, but rather on the side.

The gate was built on a rectangular plan. It had three storeys. In the lowest one there was a semi-circular passage. The plastered walls of the gate were decorated with elements fashionable at the time of its construction. The corners were adorned with decorative rustication—ornamentation that was intended to imitate brick. There were also round shooting windows in the walls. The top of the gate was topped with a decorative Renaissance parapet wall.

In the vicinity of Poboczna Gate, there was a royal bell-foundry from the mid-1730s, headed by Daniel Tym. Prior to the Swedish Deluge, more than a hundred gunmetal cannons had left the factory. They were used not only in Warsaw, but also in many other fortresses across the Commonwealth. The bell-founder would also cast bells and artistic objects to order and to cater for the needs of the royal court.

The neighbourhood of the Poboczna Gate was a strategic location during the Swedish occupation of Warsaw in 1656. The area in front of the gate was fortified by the Swedes, who were defending themselves within the city walls. Thus, they wanted to make the task more difficult for the Polish troops trying to reclaim the city. It was here that a fierce battle took place in early June 1656. Polish soldiers tried to take back the cannons stolen by the Swedes. This resulted in heavy losses on both sides. The gate was destroyed at the time, but reconstruction works began the following year.

Later on, the building was used as a dwelling, rented for an annual rent. Interestingly, around the mid-18th century, an executioner lived there for ten years. At the end of the 18th century, the already very dilapidated building, in danger of collapsing in fact, was declared completely useless. Its image shortly before demolition was immortalised by the painter and draughtsman Zygmunt Vogel. A few years later, in the early 19th century, the gate was demolished. Today, only the remnants of its foundations are to be found under the stones paving Wąski Dunaj Street.

THE KNIGHTS’ TOWER [RYCERSKA]

Let us enter the Zwinger area to take a look at the Knights’ Tower, unusual in its form. It is located in the inner line of the wall and was built already in the first period of the construction of the Warsaw fortifications, shortly after the town was founded. It was also called the Knights’ House.

Already from afar, the Tower draws attention due to its height—it rises to more than 13 metres, even though it was slightly lower in the first period. The crowning fifth storey of the tower was added towards the end of the 14th century. It has a quadrangular form, measuring 7 x 4 metres, and is open from the side of the town. It served as a seat for the guards. Inside, each storey of the tower had platforms on which the city defenders kept guard. Wooden ceilings provided an opportunity to walk over the top of the defensive walls.

Shooting windows have survived at the very top of the Tower, their form changing over the centuries. The openings below were walled up at the turn of the 17th century, creating decorative niches.

In the 17th century, the Tower, which had served the town’s defenders for three centuries, was sold and the new owner encircled it with a new wall and used it as a dwelling. The building continued to be called the Knights’ House. Over time, however, it was almost completely swallowed up by residential development. As a result, it has survived to the present day almost in its original form. The pre-war tenement houses supported by the Tower’s walls were destroyed during the Second World War. What remained was the solid structure of the Knights’ Tower. Soon after the War had ended, conservation officers cleaned it, uncovering the 14th-century walls.

The Knights’ Tower also gave its name to a nearby street, which used to be a route for the guards patrolling the section from Poboczna Gate to Krakowska Gate. Let us now continue along Podwale Street to where Piekarska Street runs off from the Market Square. Another tower in the line of the Old Town fortification was located there.

THE RED TOWER [CZERWONA]

The Red Tower, which does not exist today, was erected in the first period of wall construction, even before 1339. It was located right here, at the exit of Piekarska Street, in the inner part of the fortifications. In the 17th century, there was a passage in the wall of the Tower or in its immediate vicinity.

In the 1870s, Franciszek Maksymilian Sobieszczański, a distinguished researcher and chronicler of the history of Old Warsaw, described this defensive element of Warsaw city walls as follows: “The tower most often mentioned in the historic records and celebrated; here, the most fierce battle took place during the assault of Warsaw on 1 July 1656” by the Swedish army.

The Tower also played a major role during the assault in the following year, when Polish troops put up fierce resistance against the advancing Transylvanian army. As a result, the Transylvanians used gunpowder to blow up the Tower. Later, it was repaired several times. It was dismantled as late as the turn of 19th century, in connection with connecting Piekarska Street with Podwale.

Today, only the remnants of the foundations of the once important Tower can be found beneath the street’s cobble stone.

We now re-enter the Zwinger area and proceed towards Castle Square. On the way, on the right, we pass more towers of the outer wall. They were erected along with the Warsaw fortification in the period from the second half of the 15th century until the beginning of the 16th century. They had a semi-circular shape and were closed with a wall from the side of the Zwinger. Each tower usually had three storeys. The middle storey was accessible to the city defenders from the level of the Zwinger, and the top storey from the defenders’ pavement. The upper and middle tiers had shooting holes. At the same time, the towers were topped with the battlements, which made it possible to shoot and at the same time shield against enemy fire. It is likely that the Tower’s top was covered by a conical brick helmet like the one we saw on the Gunpowder Tower. Unfortunately, we are unable to reconstruct the events that took place in them.

In the context of towers and city walls, it is also worth mentioning an organisation of the Old Warsaw burghers, which was set up to defend the city. This was the Fowler Brotherhood [Bractwo Kurkowe], a shooting association consisting of citizens who were able to bear arms and obliged to defend the city. Brotherhoods of a similar type operated in other cities as well. The Warsaw branch was founded before 1539.

The members of the organisation constantly improved their competence and defensive skills by practising archery, crossbows and later also firearms. Since the founding of the Brotherhood, shooting competitions were held every year. The target of the shooting was usually a rooster, known at the time as a male hen [kur, hence the name ‘kurkowe’]. The best shooter was awarded not only the title of the Fowler King, but also additional prizes, such as a cash prize and exemption from night watch on the defensive walls.

THE KRAKOW [KRAKOWSKA] GATE

We shall end our walk by the last element of the Warsaw fortifications, which nowadays is largely non-existent, however in the past—in all likelihood—was the most important. From the south, the city gate led to Senatorska Street and to Krakowskie Przedmieście, later continued as a tract leading to the capital city of Krakow.

Proportionally to its importance, the Krakowska Gate was referred to by all sorts of names over the centuries. In the first centuries of the Warsaw fortifications’ existence, it was called the Courtiers’ Gate. Later, it was referred to as the Bernardine Gate due to its proximity to the church and monastery of the Franciscan friars. Slightly less frequently it was also called the Czerska Gate, thus referring to the former seat of the Mazovian princes in Czersk.

The form of the gate changed over the centuries. Initially, it was a tower built on a square plan with a passageway. Later, in the 15th century, when the outer defence wall was built, a rectangular foregate was also erected. It was protruding beyond the line of the wall, built on a Gothic bridge over the Old Town moat. Like the New Town Gate, the entrance to the foregate was possible via a lowered drawbridge. In addition, at night and in times of danger, the crossing was protected by a portcullis.

Ten years prior to the Deluge, the Column of King Sigismund III was erected in the very proximity to the Krakowska Gate. Thus, the southern entrance to the city gained in prestige and significance.

The Krakowska Gate was also fortified by the Swedes—an element of the southern fortification was destroyed during the Deluge and then rebuilt. At that time, it was a building covered by a hipped roof. Above the passage there was a residential room rented by the town. The outbuildings of the Royal Castle were adjacent to the tower and the foregate.

Further changes were made to the appearance of the southern entrance to the town in the second half of the 17th century. The existing form of the gate in the line of the inner rampart was boosted by adding a tower, clad with sheet metal with a spherical cupola. The entrance gate with a passage in the lower storey was also substantially rebuilt and raised by one storey. The façade facing Krakowskie Przedmieście was decorated with new, period-inspired ornaments. The ground floor elevation was embellished with rustication while the floors above were decorated with shallow columns called pilasters. The gate top was adorned with a triangular pediment, above which five stone sculptures were placed. To the right and left, townhouses of the same height were closely adjacent to the Krakowska Gate. The form of the southern entrance to the city at the end of the 17th and 18th centuries already bore little resemblance to the former defensive structures.

The Krakowska Gate, the surrounding buildings and the remnants of the defensive walls next to the gate were demolished in 1818. Zamkowy [Castle] Square was delineated at the time. At the end of the 1970s, archaeological excavations were carried out here. The relics of the Gothic bridge under the gate were uncovered and preserved. The foundations of the former defensive wall were raised to street level and made visible in the paving of Zamkowy Square.

Together with the Gothic bridge of the former Krakowska Gate, the moat—buried in the 19th century—was also reconstructed. Very interesting finds testifying to the life of the residents of Old Warsaw were discovered there. Many of them can be seen at the exhibition The Things of Warsaw at the Museum of Warsaw. We encourage you to come and see for yourselves!

Here, on the bridge by the entrance to the Old Town, next to the King Sigismund III Column, our walk comes to an end.