10.10.2023 / Activities, News, Walking tour

Old and New Town in Warsaw

Walking tour. Warsaw’s historic quarter as an architectural miracle, an impressive tribute to the city’s will to survive.

Theoretically The Old Town is the oldest part of the city, the place where the history of Warsaw began. In fact it is one of the youngest districts. Thanks to the efforts of all Poles, it was carefully rebuilt after total destruction during the Second World War. The phenomenon of this reconstruction makes it absolutely unique!

Let us take you for a walk and show you the results of the unbelievable reconstruction of Warsaw’s Old Town. Compare the new buildings to the original pieces that survived. Feel the atmosphere of currently the most charming corner of the city.

How to prepare?

Bring headphones, a charged phone or take a powerbank, and put on comfortable shoes (cobblestones). You will need a camera (it can be the one on your phone) to take pictures.

Duration: about 1,5 hour

For whom: English-speaking youth and adults curious about the history of Warsaw

The beginning of the walk: Sigismund’s Column, a popular meeting place

Find the starting point on the map – the Sigismund’s Column. The map will help you to locate the other stops and places that we will talk about.

Author: Agnieszka Tomaszuk (Warsaw guide)

Language consulting: Zofia Siwek

Historical consulting: dr Krzysztof Zwierz

Recording: Hanna Tomaszuk

Lector: Michalina Sozańska

Sigismund’s Column

The beginnings of Warsaw date back to the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. Due to its convenient location, mainly rich merchants settled in Old Warsaw on the trade route from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea.

It was a time when the Duchy of Mazovia existed in this area. It was incorporated into the Polish Kingdom just at the beginning of the 16th century. However, in the middle of this century, an important event took place – the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was established. Both countries were connected, and this allowed this small, trading town Warsaw to become the seat of the Polish-Lithuanian parliament. Later on, it became the capital of the whole country. Who did it? Who moved the capital from Cracow to Warsaw? Look at the high monument and the statue on the top.

This is the so-called Sigismund’s Column. On the top there is a statue of King Sigismund III Vasa, who in late 1500s moved Poland’s capital here. But did he change the capital, as it is popularly said? In fact, he only made Warsaw the residence city of Polish rulers from his times. Yet it resulted in finally making Warsaw the capital city. What was the reason for that change? More convenient, central location. Between Cracow and Vilnius. Some say that he wanted to be closer to Sweden, which was his birth place. He was in fact a son of the Swedish king. The monument was erected in 1644 and it was the first secular statue in the form of a column in modern history.

The column survived the beginning of World War II and almost the entire occupation. It collapsed during the Warsaw Uprising, when on the first night of September 1944, it was hit by a German tank gun. The shaft fell apart. King Sigismund‘s statue returned to Castle Square in 1949. It stood against the ruins of the Old Town as a symbol of the rebirth of the city.

The shaft of the column, damaged during the war, lies on the ground next to the Royal Castle. Next to it lies the first shaft of the column which was replaced because of its poor condition. You can go there and even touch both shafts. The statue of King Sigismund, despite falling from a height, survived, although some individual parts were damaged.

The statue of the king on the present monument is placed very high, it is difficult to see it. Fortunately numerous miniatures of the monument were made. They could be given, for example, as a souvenir. Thanks to such miniatures, we can see the details of the statue.

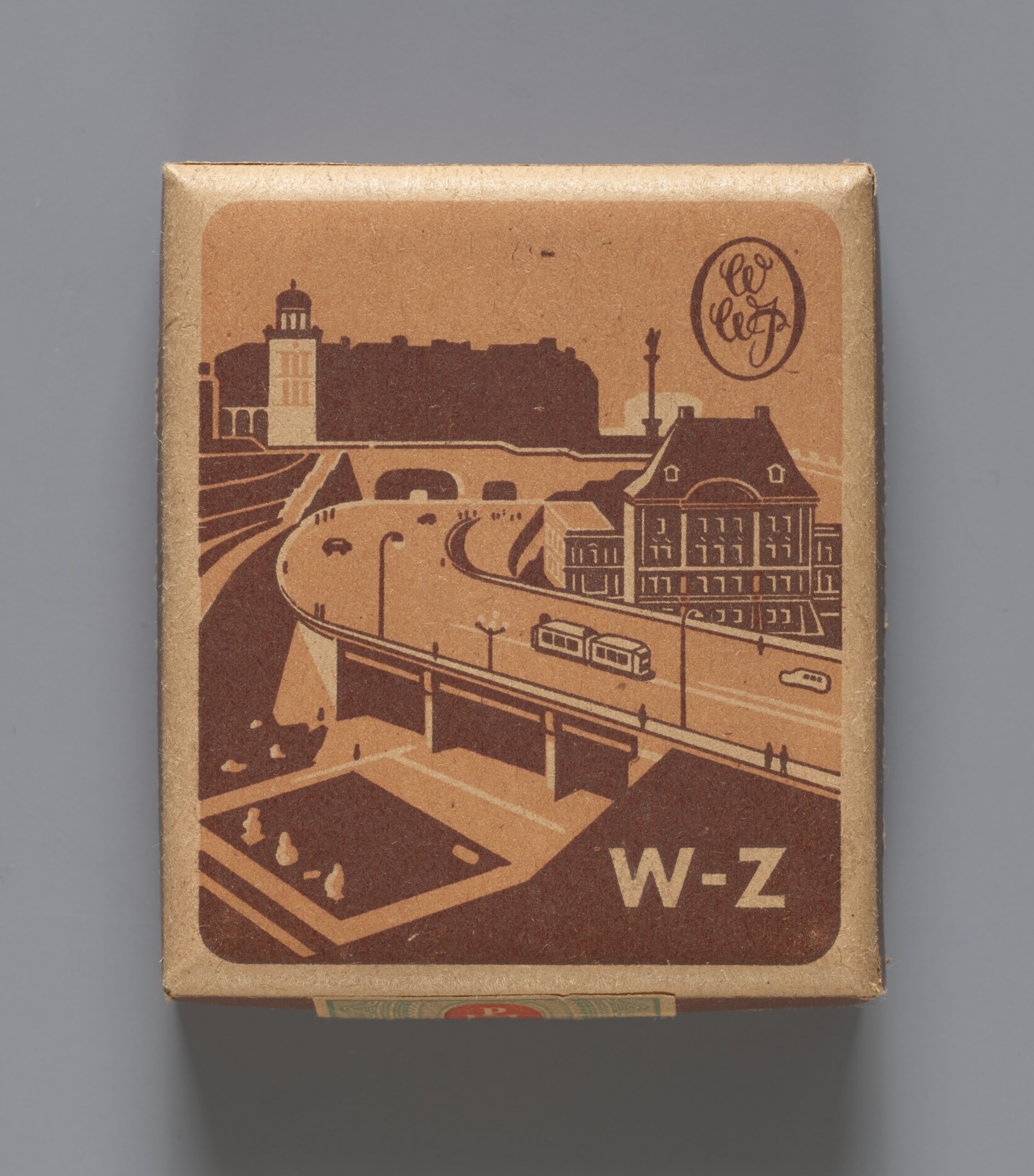

Tunnel of W-Z Route and escalators

If you are standing looking at the column, then there is a building behind you. Go inside and you will find the escalators. They are part of the route called W-Z („W” stands for east and „Z” for west) Go down the stairs to see it.

The post-war reconstruction was an opportunity to fill the gaps in the pre-war city. One of the problems in terms of communication was the lack of a convenient connection on the east-west line. So the construction of the new artery started. It was built partly in a tunnel, which was made using the opencast method. This was allowed by the scale of destruction of the buildings standing above. They were dismantled and then reconstructed. The route was ready in 1949, together with the escalators connecting the street level with the Castle Square. Today, we have escalators everywhere. But in those days, after the war, there were no such stairs in Poland yet! So the escalators immediately became a tourist attraction.

The entire construction of this route was one of the largest investment in the first years after the war. The decorations of it are also a perfect illustration of the so called „socialist realism”, propaganda art. Find two bas-reliefs located by the escalators that are a great example of the style from the beginning of the communist period. And come back, upstaris, to the Sigismund’s column.

Cigarette smoking in the middle of the twentieth century was very popular and widespread. Because of that, the packages became something more than just packages, they had their own message. In communist Poland, they included propaganda contents. The packaging of cigarettes was used to talk about the idea of rebuilding the capital. In honor of the W-Z Route built in 1947-1949, a brand of cigarettes was created.

UNESCO stand

If you are already at Sigismund’s column again, go now towards the city walls. Such a post as in the picture below, will show you the direction.

The effort and the enthusiasm of Poles in bringing the Old Town back to life, was recognized by UNESCO. In September 1980 Warsaw’s Old Town and the Royal Castle were inscribed on the World Heritage List. It was an expression of great respect and admiration for the Polish architects, conservators, historians, art historians and ordinary workers, but also all the inhabitants of Warsaw who did not give up and kept showing their great love for this city.

The UNESCO zone is marked by posts made of Scandinavian granite. Each bears a bronze miniature of the Old Town and an inscription in five languages (Braille, Polish, English, Spanish and French):

“The historic centre of Warsaw entered on the World Heritage List”.

Jan Zachwatowicz monument

In the 13th century, the town settlement was surrounded by a rampart, which at the end of the 14th century was replaced by a defensive wall. Its fragments, also the reconstructed ones, can be seen on the left to the Sigismund’s column.

Between the two lines of the defensive walls, you can find a monument honoring Jan Zachwatowicz. He was the main architect recreating the Old Town after the war.

Professor Jan Zachwatowicz is also the author of the white and blue sign that you will find on many buildings in the Old Town. This is Blue Shield – the cultural equivalent of the Red Cross. It is a symbol of protection defined in the 1954 Hague Convention dedicated to the protection of historical places in case of war. The sign is used to mark cultural objects to show that they are protected in the event of an armed conflict. Blue Shield is also the name of an organization that creates a network of cooperation between various cultural institutions, museums, archives, and libraries.

Royal Castle

The Royal Castle was first a ducal castle. It was a home of the dukes who belonged to the same dynasty as the Polish kings but ruled independent Mazovia. After the death of the last dukes, two brothers, Stanisław and Janusz, Mazovia was incorporated into Poland. When the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was established, the Castle was designated as the permanent place of sessions of the parliament of the United Commonwealth. Then Sigismund III Vasa, the king on the column, extended it and made it the official residence of Polish rulers. After World War I, it was the seat of the Polish president. During World War II, in September 1944, it was blown up by the Germans. There was practically nothing left of it, apart from fragments of decorations and works of art, taken out of the Castle by it’s staff, hidden and thus saved from destruction. They can be seen in the rebuilt Castle, which is a museum today.

However, a lot of time had to pass before the opening of this museum. The decision to rebuild the Castle was made immediately after the war, but the reconstruction did not take place. Again, it was decided to rebuild the Castle in 1971, and then the work began immediately.

The Civic Committee for the Reconstruction of the Castle was established, because the Castle was to be rebuilt with the financial resources of the entire nation. A huge money box stood on Zamkowy Square. Donations came from all over the place.

Efforts were made for the rebuilt castle to resemble not the pre-war one, but the one from the Vasa era. The interiors, on the other hand, mostly date back to the times of the last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski. In the castle you can also admire many original elements saved by the castle staff, often risking life, during the war, as well as those dug out of the ruins.

The castle was officially opened to visitors in 1984. This did not mean however that the whole complex was fully rebuilt. Between 1994 and 2009 the Kubicki Arcades, built in the early 19th century, one of the few saved parts of Royal Castle, were restored. Until 2015 the Upper Garden, located on top of the Kubicki Arcades, was meticulously restored too. The last part of the reconstruction of the Royal Castle complex took place in May 2019 when the Lower Garden was rebuilt and reopened to the public.

Professor Stanisław Lorentz, director of the National Museum and a great advocate of the reconstruction of the Castle, did not hide his emotion:

“When we inaugurated the reconstruction […] we remembered the times when in September 1939 we saved the burning castle, when we took everything that was more valuable to the underground of the National Museum when we later cut out arabesque wall paintings, samples from architectural and sculptural details of each of the historical rooms, all in order to be able to reconstruct the castle as faithfully as possible. We were sure that this moment would come.”

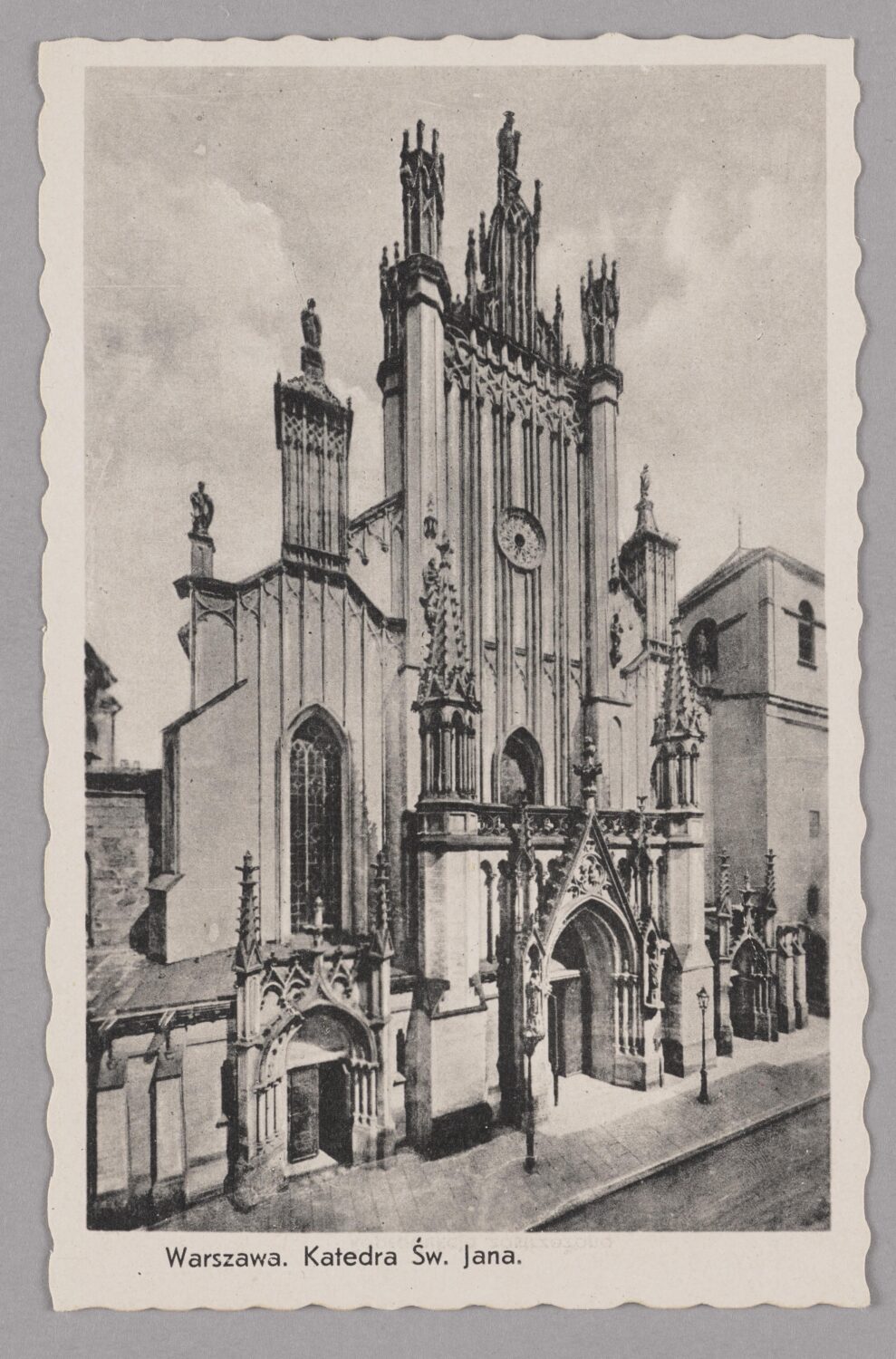

St. John’s Cathedral

St. John’s Cathedral is the oldest church in Warsaw. The first wooden chapel was built at the beginning of the 14th centuries. At the end of the 14th century there was already a brick, gothic church, which over time became an increasingly important temple. Currently, its full name is the Archcathedral Basilica dedicated to the Martyrdom of Saint John the Baptist and is the seat of Archbishop of Warsaw.

This church has witnessed many historical events, such as the coronations of two kings, who ruled the country in the 18th century: Stanisław Leszczyński and Stanisław August Poniatowski. The Holy Mass was celebrated here after establishment of the second in the world, and the first in Europe, modern, democratic Constitution of May 3rd, 1791. It was another crucial historical event.

Many famous people were buried in the cathedral. Here rest the ashes of the last Mazovian dukes, king Stanisław August Poniatowski, presidents of the Republic of Poland Gabriel Narutowicz and Ignacy Mościcki, a great writer, Nobel Prize winner Henryk Sienkiewicz and musician and statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski, as well as Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, who was the head of the Catholic Church during communism.

This church was destroyed during World War II and then rebuilt but… in a different form. Before the war, it was in the style of English neo-gothic, and now it is an example of local Mazovian gothic style. The reconstruction project was made by Professor Jan Zachwatowicz, whose monument I hope you managed to find earlier by the city walls.

Bell on Kanonie

At the back of St. John’s Cathedral is Kanonia Street in the shape of a three-sided square. It was built on the site of the Old Town cemetery, which was liquidated a long time ago. There is also a bell on the square. It was made at the beginning of the 17th century in the bell foundry workshop of Daniel Tym, a well-known bell maker, who casted a bronze statue of the king from Sigismund’s Column. At first, the bell was supposed to go to a church outside Warsaw, but it was decided that its sound was not appropriate. After the war, it found its place in Kanonia and people say that it is a magic bell that fulfils wishes. Just think of a wish and touch the bell. Some say that you should additionally walk around it, preferably jumping on one leg.

In the gap between the two corner tenement houses, there is “squeezed” a narrow building, probably the narrowest tenement house in Europe. Try to discover the secret of this house. Is the whole house really as narrow as it looks?

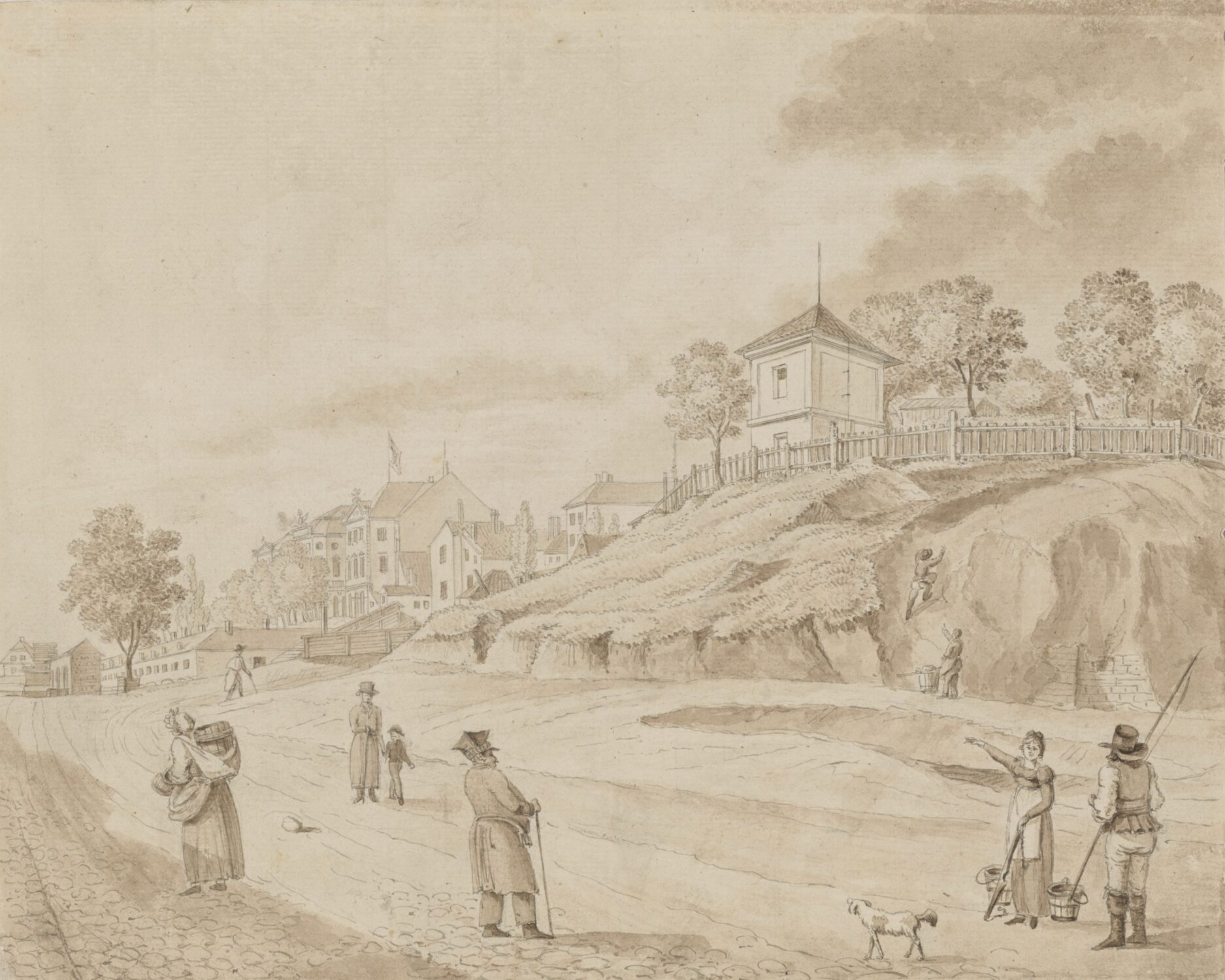

Gnojna Góra

You are on a nice observation deck, from which you can see a vast panorama of the Vistula valley. Vistula or Wisła in Polish, is the biggest and the longest Polish river. Its right bank is called Praga and it is mainly a residential district. However, it was not always so charming on this terrace. The inhabitants of these tenement houses not only did not have such beautiful views, but in addition they were tormented by the unpleasant smell around. This terrace is located in a place traditionally called Gnojna Góra, which means „Dung Mountain”

Probably from the beginning of the history of the town to the early 18th century, a garbage dump functioned here. Attempts were made to eliminate it much earlier, because it was extremely burdensome.

Before the war, there was even a large building erected on this site, but it was not rebuilt after the war damages. Eventually, a nice observation deck was created for this place, but the ugly name remained.

There is also a new tradition, known also in other countries – the tradition of lovers placing padlocks here.

At the corner of Celna and Brzozowa streets, a picturesque fragment of the gothic wall from the late 14th century draws attention. The tenement house partly survived after World War II, and the rest was rebuilt by incorporating part of the former Brama Gnojna (Dung Gate) together with a fragment of the building from the fourteenth century, probably serving as a granary.

Continue along Brzozowa Street and on your left you will see large wooden gates. This is the entrance to the branch of the Museum of Warsaw called the Heritage Interpretation Center.

The Heritage Interpretation Center

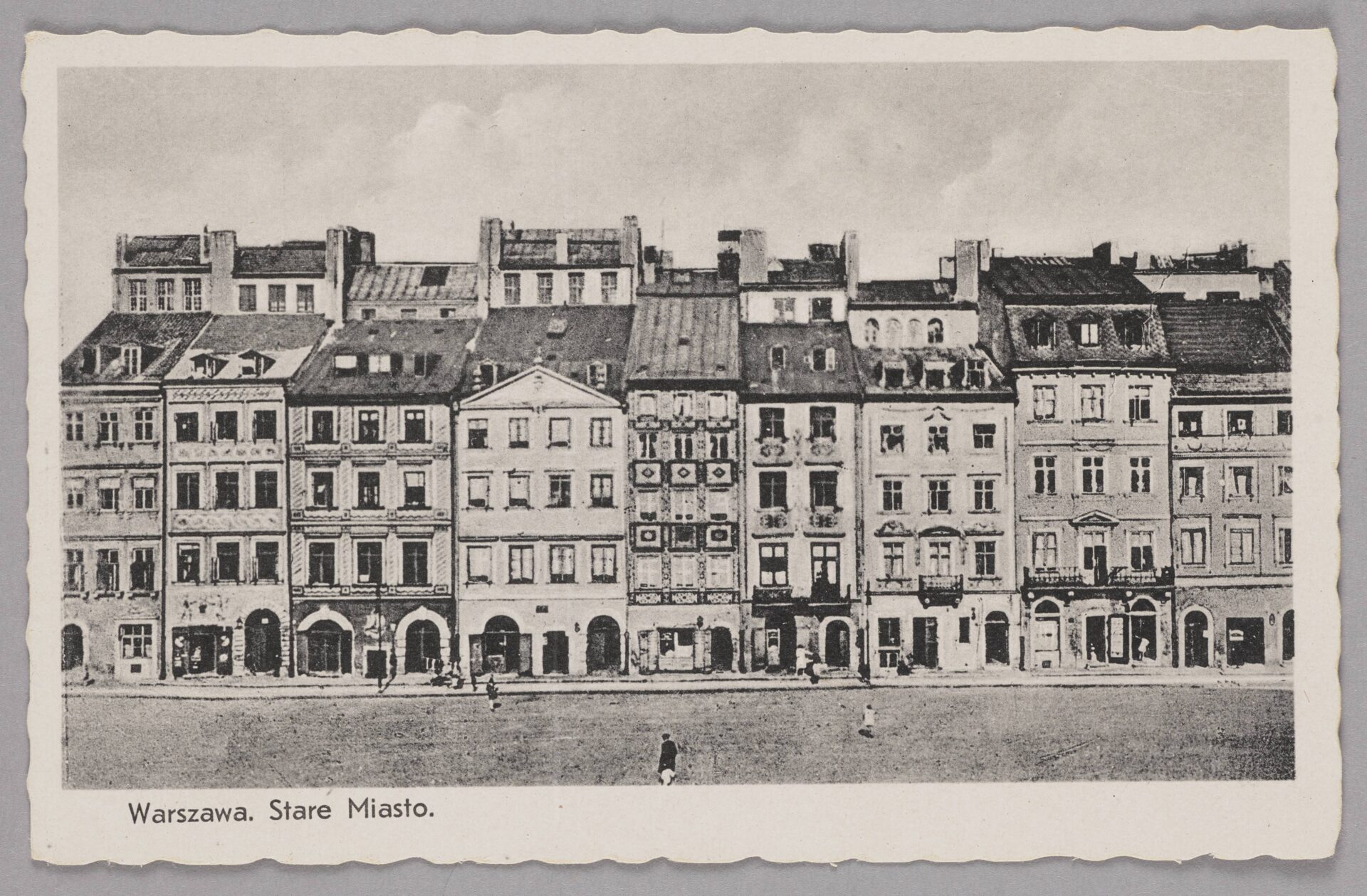

The reconstruction of Warsaw’s Old Town is a phenomenon on a global scale. This is what makes Warsaw’s Old Town unique. It does not surprise with its size, it is actually very small. Its layout and form resembles other European Old Towns that were created at the same time. However, it is exceptional, because it has been rebuilt so that today it looks like it is really old! It was the first attempt in the history of the world to reconstruct the entire historical centre of the city, not only its most valuable monuments.

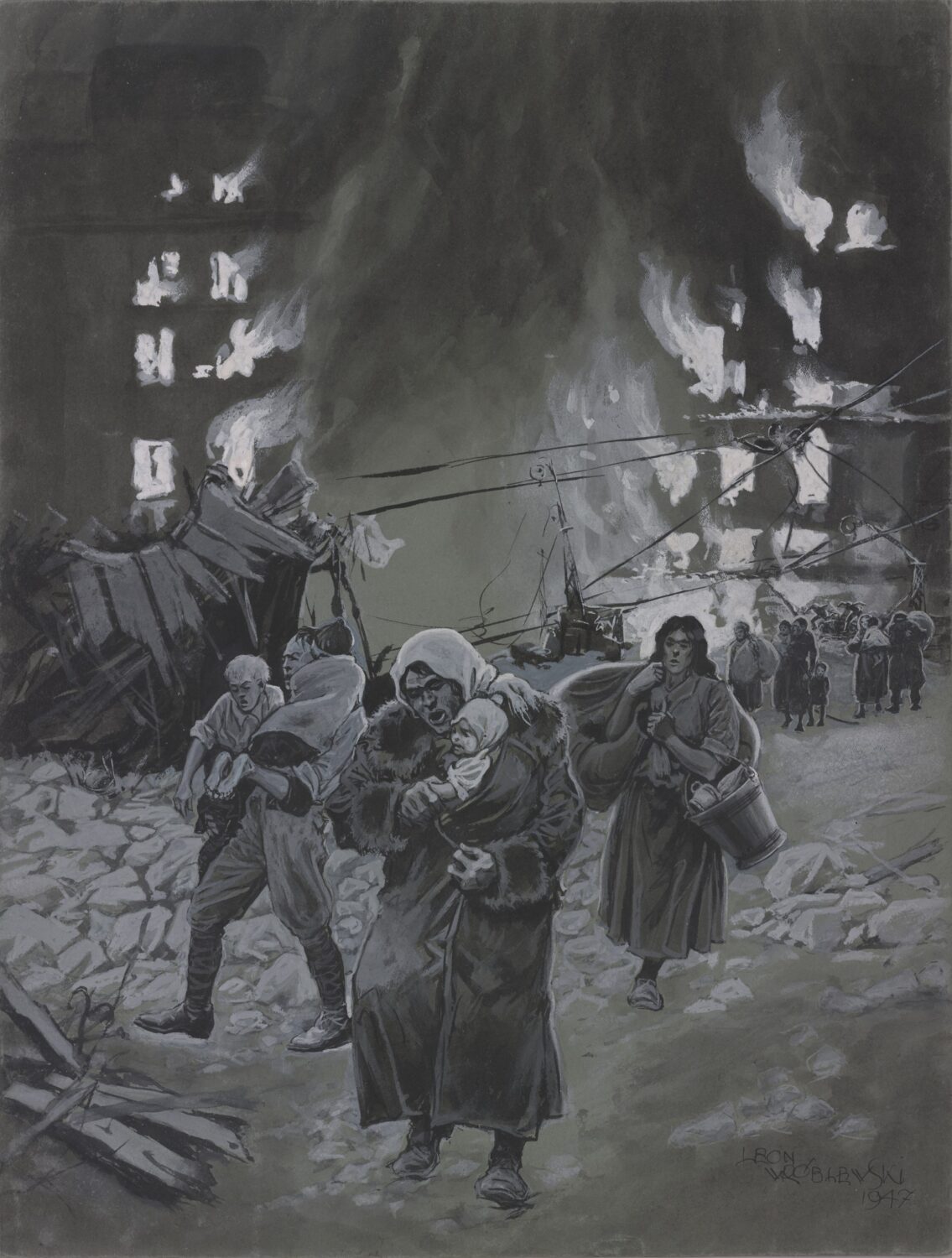

Warsaw after the war really looked like an ocean of rubble. Its reconstruction seemed impossible. Various other scenarios were considered, but thanks to the inhabitants of the city, who immediately after the war simply began to return to the city, and also thanks to people such as Professor Jan Zachwatowicz, whose monument you saw earlier, the idea of reconstruction won.

Immediately in 1945, the Warsaw Reconstruction Office was established, and in 1949 the government made the final decision to reconstruct the Old Town, as part of the six-year plan. First, however, hundreds of tons of rubble had to be removed and the remaining ruins secured, but the enthusiasm was enormous. The implementation of one of the most ambitious projects in the history of mankind began. And already in 1953 the Old Town Market Square was officially opened. So the reconstruction of the Old Town was very fast, it took 4 years only.

How was such a huge undertaking possible in a country so economically devastated by war? The source of financing was the Social Fund for the Reconstruction of the Capital City. The fund was nationwide, the money was obtained from the compulsory taxation of all working people. In addition, some products were taxed, income from cultural and artistic events and fundraisers among people was collected. Many people worked voluntarily. The current political system with centralized power made it possible to allocate a large amount of national financial resources for this single purpose. As the communist propaganda proclaimed, the whole nation rebuilt its capital.

We invite you to our museum for more information about the reconstruction process and for the stories of people involved in it. We have photos, statistics, documents and objects, and we will even show you how architects used to work when there were no computers and plans were drawn by hand!

Main Square

The Old Town Market Square is today the true heart of the Old Town. Until the end of the 18th century it was the heart of the entire Warsaw, but in 1817 a town hall on the Market Square was demolished as the Old Town ceased to be the city centre and became a poor and neglected district.

However, in the Middle Ages, it was the centre of trade, lined with merchant stalls. The buildings on the Market Square were mainly wooden. Later, brick buildings started to appear. After the fire in the beginning of the 17th century, the buildings were rebuilt, later other smaller and larger changes were made and they were finally destroyed mainly in 1944.

Warsaw Mermaid

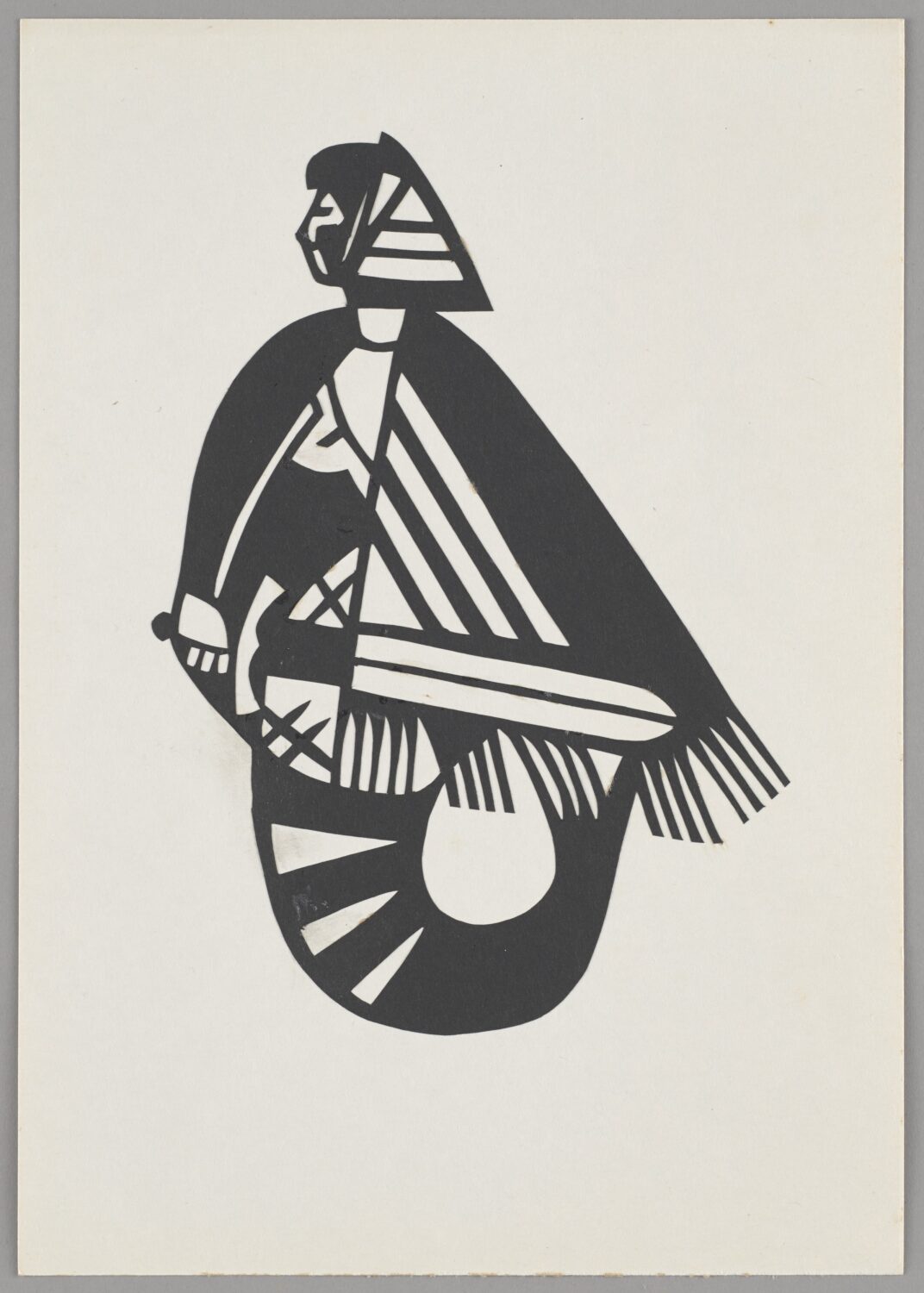

Polish people call her Syrenka which means Mermaid. She does not have a special name. It is one of the symbols of the city and is presented in the coat of arms of Warsaw. It is half woman, half fish, always depicted with a shield and a sword.

It is a surprising symbol considering the fact that Warsaw is not located by the sea, but it is located on the side of the largest Polish river – Wisła. And, according to legend, that is where Syrenka lives to this day.

There are many versions of this legend. There is a version that presents her as the one who tangled the fishermen’s nets, but delighted them with her wonderful singing. Another version says that she was the one who indicated the place, where Warsaw was later established.

Anyway, all stories assign her the role of patroness and protector of the city.

We will tell you more about the history of the coat of arms of Warsaw in another place. Now be sure to take a picture with one of the most beautiful Warsaw mermaids!

The monument, which now stands in the middle of the Market Square, was created in the mid-19th century, when the first modern waterworks designed by Henryk Marconi were being built in Warsaw.

The sculpture was designed by Konstantin Hegel and became part of the fountain, in the form of artificial rocks. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Mermaid disappeared from the Market Square and wandered around Warsaw. Fortunately, it survived the war, it was only slightly damaged, but it returned to the Old Town only in the 70s but not immediately to the Market Square. At first it stood on the defensive walls, but it was not safe there, so it was eventually moved to its original place, to the Old Town Main Square. Unfortunately, it was often devastated in this place, too. And here I will tell you a secret. So that this original, 19th-century sculpture would never be destroyed again, in 2008 we hid it, and you are looking at a faithful copy of it. Where can you find the real Mermaid? In the Museum of Warsaw!

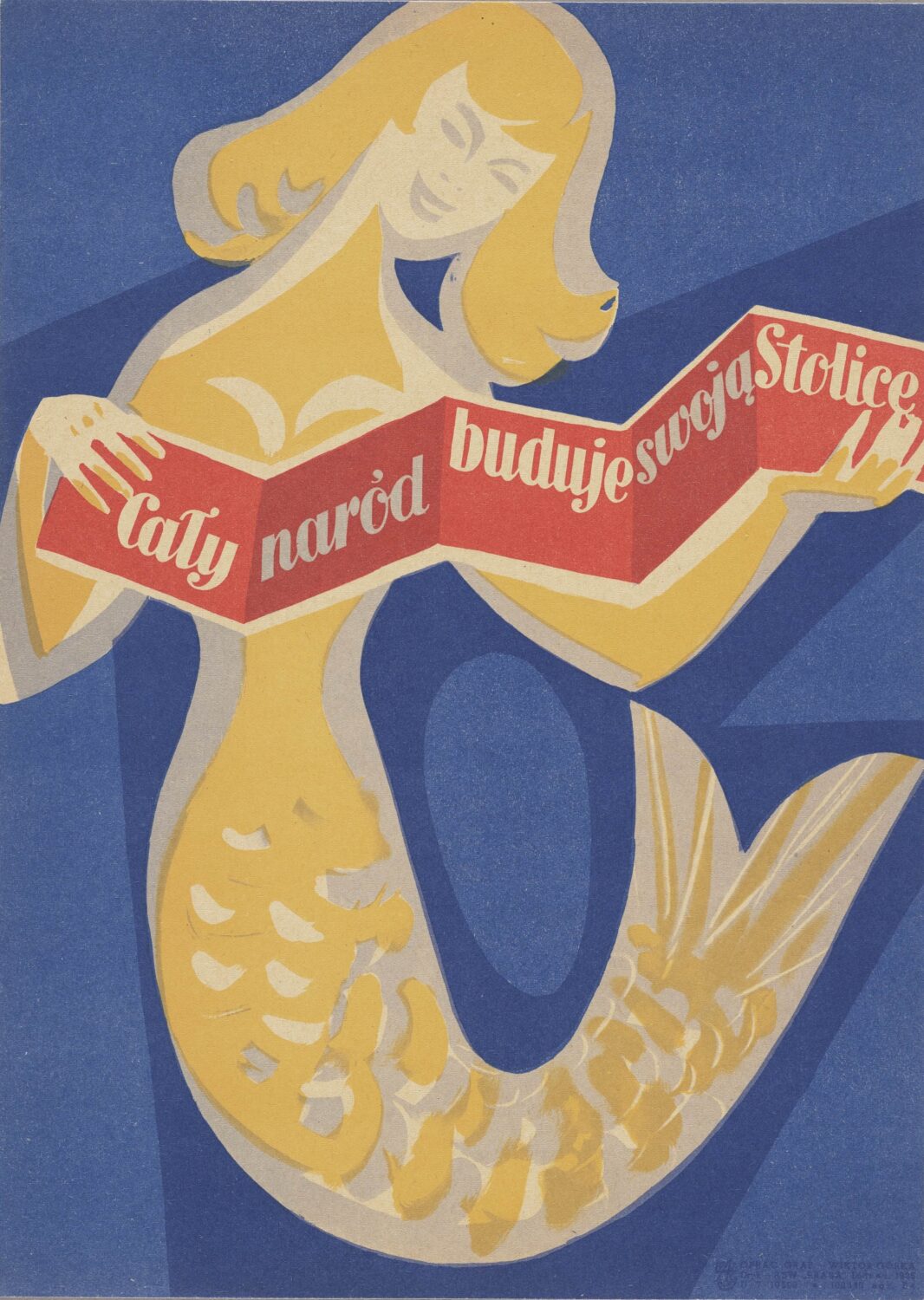

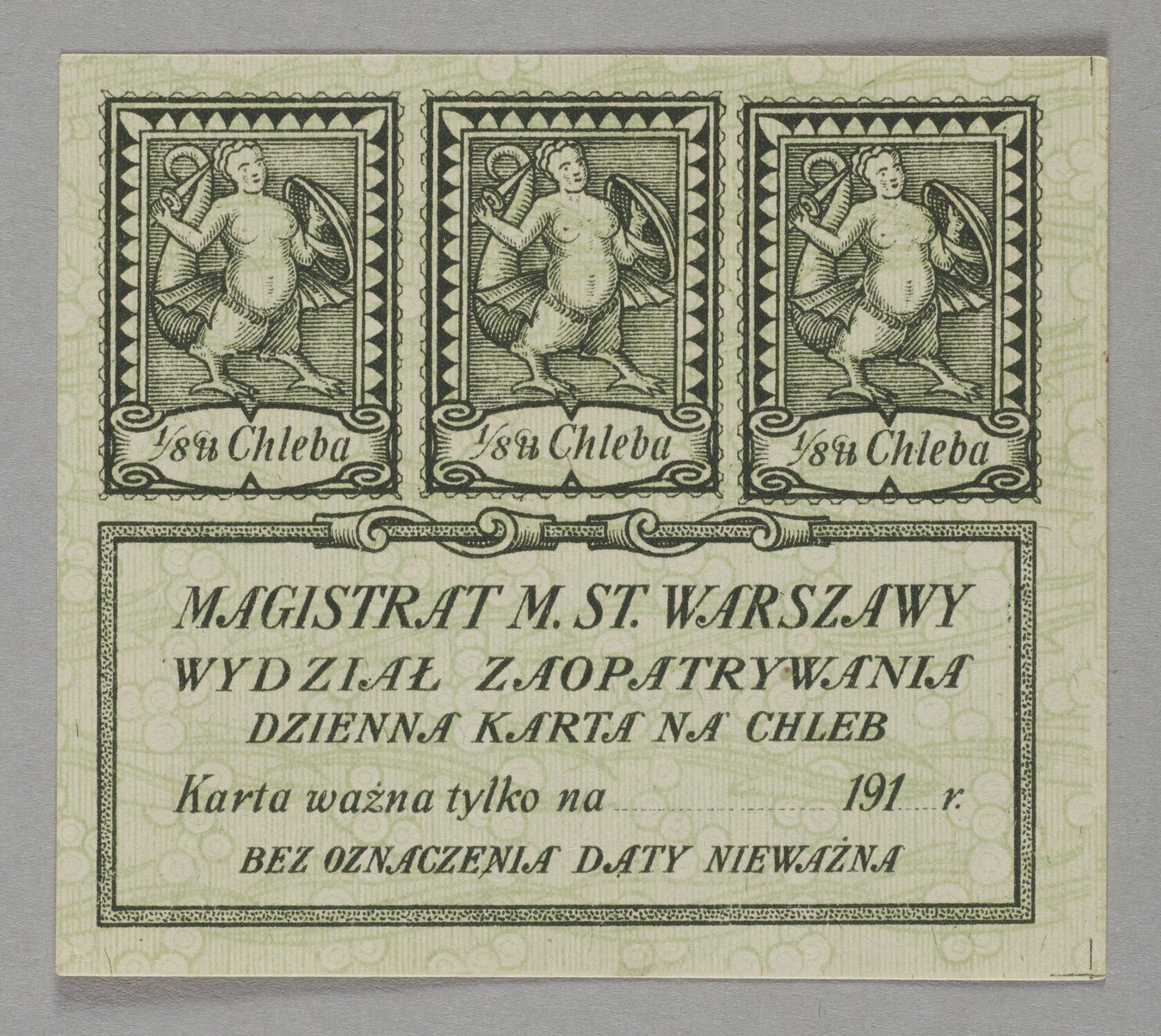

The mermaid motif was also used for propaganda purposes during the reconstruction of Warsaw, because

“The whole nation is rebuilding its capital!”

Museum of Warsaw

Our museum, the Museum of Warsaw is an extraordinary museum. A museum that uniquely combines the old with the modern. It is located in old tenement houses. Of course, rebuilt after the destruction of the Second World War, but this side of the Old Town Square, called the Dekert side, after one of the mayors of the old Warsaw, has survived to the greatest extent. Therefore, apart from the fact that the museum building itself is old, the objects presented in there can also be classified as old ones, more or less, but still from the old days. And they are authentic items. However, the form in which they are presented is very modern. And the museum itself, as an institution, is also very modern and open.

Keynote of the museum is: Extraordinary Stories Of Ordinary Things.

The Museum of Warsaw collects the things of Warsaw, researches them and makes them available to the public. The core exhibition refers to the histories of particular objects in order to speak about historical events and people who had made an impact on the shape and character of contemporary Warsaw.

Visit us and check how you find this form of narration about the history of the city.

The Things of Warsaw

In twenty one thematic rooms you can find works of art and objects of everyday use. They will tell you the stories of their owners and creators, as well as present the events and processes that formed this city in the past.

You can learn about the history of tenement houses, too and find many interesting Warsaw data in the basements. Stats don’t have to be boring!

And you can explore the exhibition your way! At your own pace and following a route you selected yourself – you can assemble your own story of Warsaw.

And… if you are interested in the history of the reconstruction of Warsaw, in our museum we even have a thematic path that will tell you even more stories related to it: muzeumwarszawy.pl/sciezkaodbudowy/

Outside the headquarters Museum of Warsaw has branches in eight other locations!

Piwna Street and The Antonina Leśniewska Museum of Pharmacy

A branch of the Museum of Warsaw, 31/33 Piwna Street.

It is one of the smallest museums in Warsaw, dedicated to the history of pharmacy in Warsaw and Poland. Its patron is Antonina Leśniewska, a precursor of women’s emancipation in the field of pharmacy and one of the world’s first pharmacists.

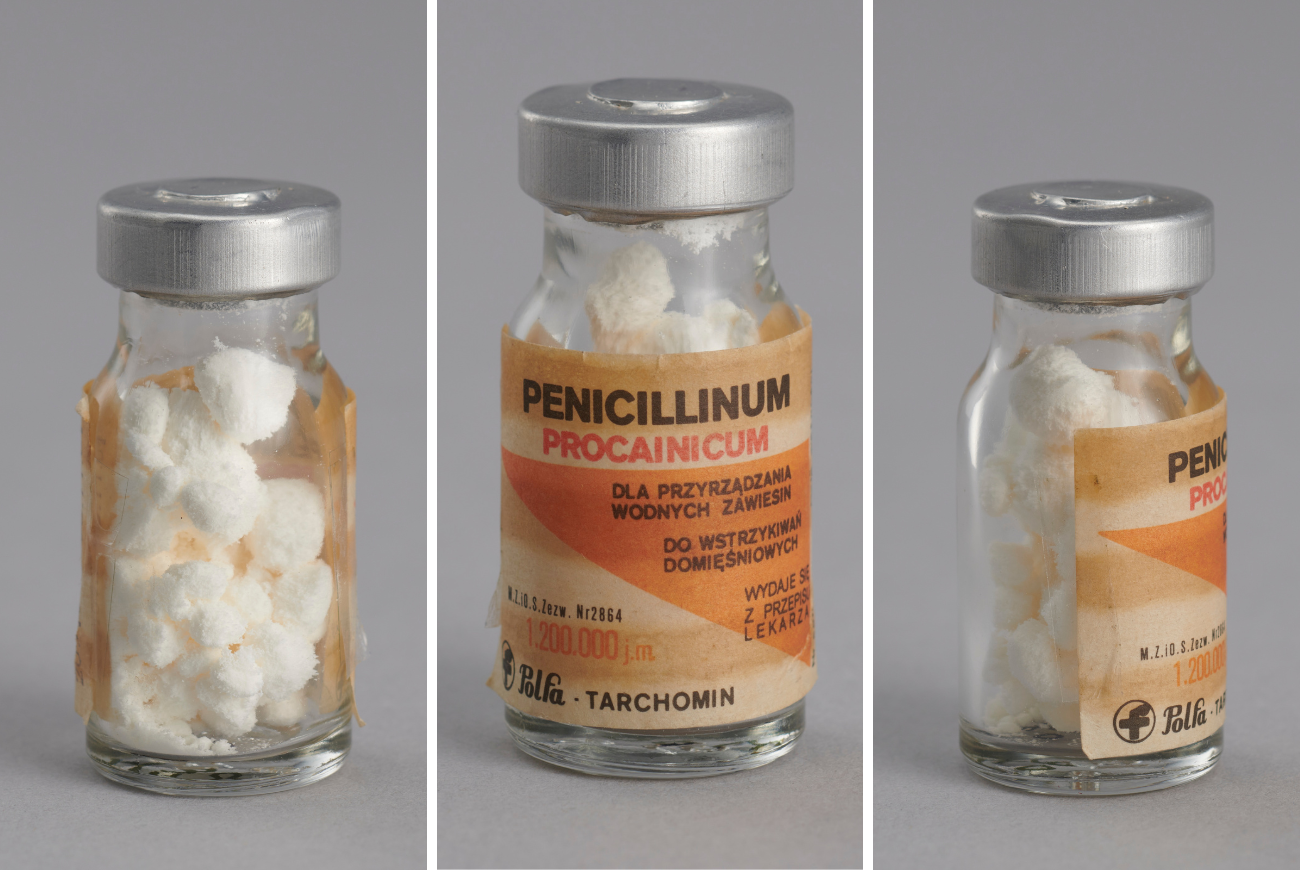

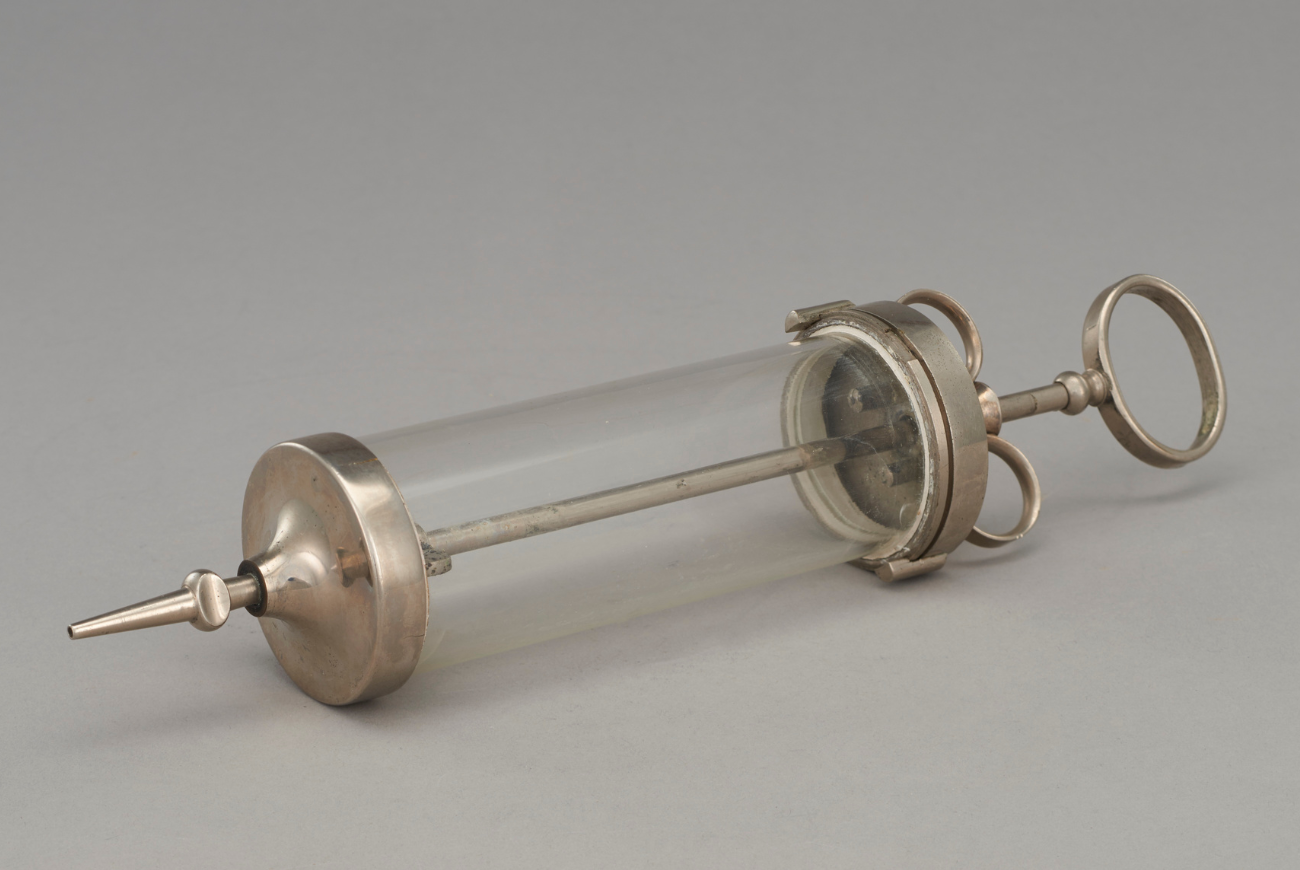

The museum has the oldest preserved pharmacy furniture in Warsaw from the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, as well as a collection of pharmacy vessels from the pharmacy operating since 1602 in the Royal Castle, excavated during archaeological research. You can also see exhibits related to various fields of medicine for example surgical, gynecological and dental instruments.

It is located on Piwna street, the longest street in Warsaw. The name means „beer street” and comes from the breweries, inns and taverns that used to be located here before.

This area can also answer the question whether the Old Town, since it is on the UNESCO list and seems so old to us now, has been rebuilt 100% the way it looked before the war?

Everything that survived – portals, window frames, wall paintings, sculptural details – was restored and built-in into the walls of new tenement houses. However, sometimes it was not possible to recreate the pre-war appearance due to the lack of information and patterns. Sometimes because of the political situation. Sometimes the changes were made deliberately.

The demographic explosion, the development of industry, mass migrations to the city, all of this made Warsaw one of the most densely populated cities in Europe before WWII.

When the city was demolished after the war, urban planners and architects had the opportunity to build it anew and modernize. What changed in the Old Town? For example, courtyards were enlarged by demolishing or not rebuilding outbuildings and other annexes erected next to tenement houses later. Defensive walls were unveiled, while the houses “glued” to them were not rebuilt. A large part of the Wisła escarpment was cleared of buildings. It was necessary to take into account the new function of this place – residential function.

It was decided to improve housing conditions, give people access to light and air. Inside, small, two- and three-room apartments were built, equipped with modern solutions, such as running water or central heating.

Regarding the decorations outside – after the Second World War, in the changed political situation, the pre-war paintings did not fit. They could not return to the facades of houses, nor could religious elements. An example is the green house at the end of Piwna Street, where, before the war, there was the statue of Jesus Christ standing at the top, defeating death, that was depicted as a skeleton. The statue has not been reconstructed, and only the skeleton remained.

But mostly the artists decided to choose the affirmation of life, the subjects related to Polish history, literature, everyday life and Warsaw legends or plant and animal motifs. Great importance was attached to metalwork in the form of signboards, door fittings and window bars.

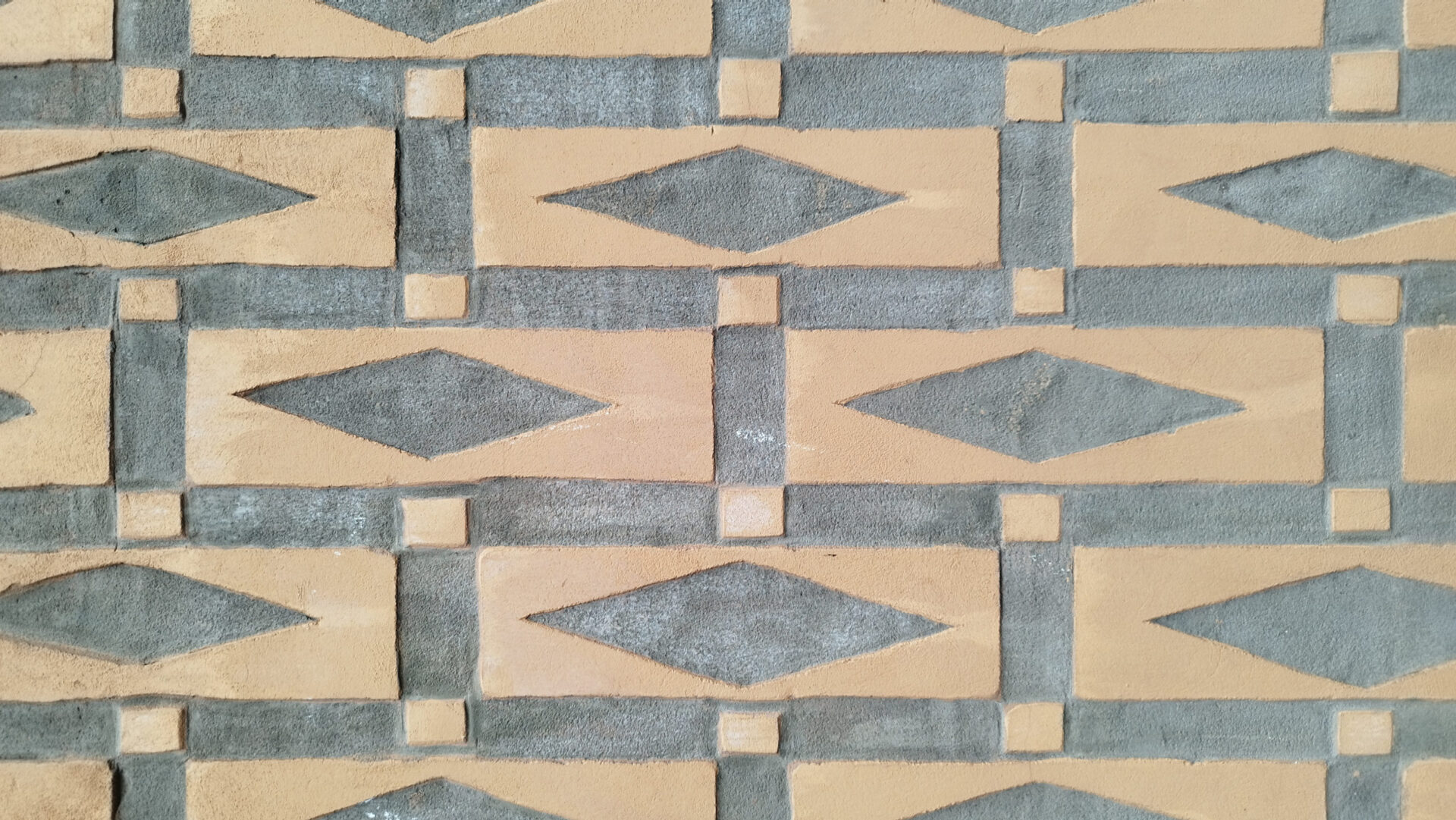

Tenement houses were decorated mainly with the sgraffito technique.

which consisted in applying successive colored layers of plaster and scraping off fragments of the top layers, so that a multi-colored pattern was created. It was technique that was simple, quick, and long lasting. You can see it all around. In exceptional cases only, the facades were decorated with paintings. Today, after subsequent renovations of the facades, beautiful paintings appear. The great example of it is the painting on Wąski Dunaj Street, that reminds of the marketplace which used to exist there.

Szeroki Dunaj

The name of this place is Szeroki Dunaj. Szeroki means wide. Dunaj could be translated as Danube but it does not refer to the famous, big river Danube. It refers to the little stream that once existed here, which had its spring where now a well stands. Szeroki Dunaj is actually a street, but it has the form of a wide square and you reach this place through a street called Wąski Dunaj. Wąski means narrow.

This square was once a marketplace. It is interesting that the only fish sold here was salted, because fresh fish was allowed to be sold exclusively on the Main Square. Many craftsmen lived here, mainly shoemakers, as the decorations on the facades say.

Look at the facade of house number 9. There you will find, between the windows, four round pictures showing how the coat of arms of Warsaw has changed. Examine from the left to the right. From the Middle Ages until today. The oldest existing image of the coat of arms of Warsaw with a mermaid appears on the seals of documents of the Warsaw City Council in the 14th century. However, for a long time, the mermaid had a completely different shape than today. The half-female, half-fish mermaid didn’t appear until the 18th century.

Polish Syrenka is related to the Siren, which in Greek mythology, is a humanlike being with an alluring voice. But she is more properly a fresh-water mermaid called melusina, a figure of European folklore, a female spirit of fresh water in a holy well or river, usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down. Sometimes it is illustrated with wings, two tails, or both. The common English translation, in any case, is neither siren nor melusina but mermaid.

In the Museum of Warsaw, we have a whole room dedicated to Warsaw mermaids!

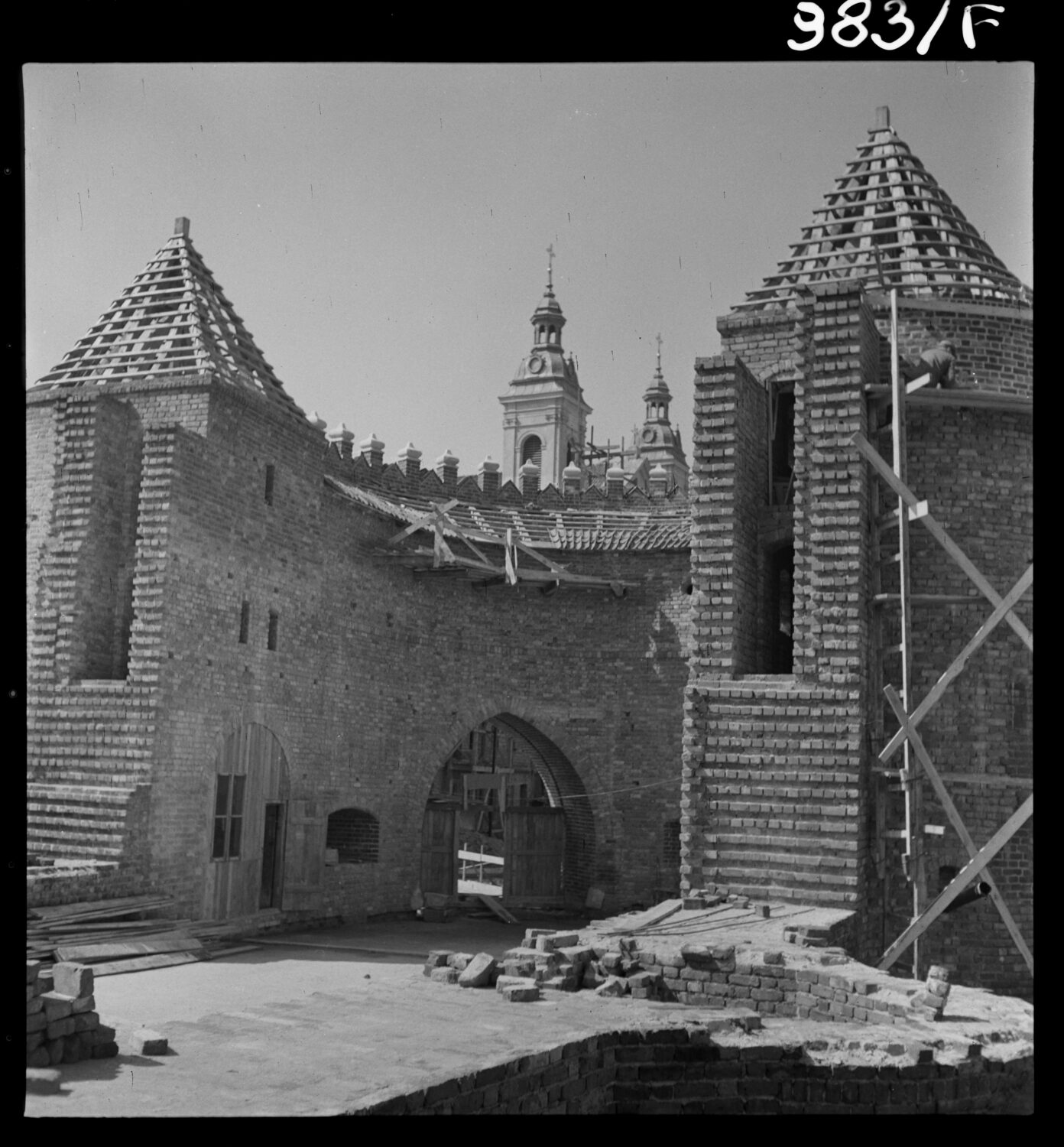

Barbican

The beginnings of the construction of the fortifications are connected to the beginning of Warsaw. The walls were necessary to protect the city. The first protection were ramparts with a wooden-earth structure. In the late 14th century, a brick wall was built, in which there were two gates and several towers. From the mid-15th century, the construction of the second, outer ring of walls began. The city also had a moat. In the 18th century, the city walls ceased to be useful. Partially demolished, in many places enclosed with tenement houses, they have survived to our times.

One of the most interesting elements of the city’s fortifications, popular in the Middle Ages, is the Barbican. It is a brick building sticking out from the defensive walls with turrets, erected on a gothic bridge. It gave additional protection, but it was also part of one of the city gates.

It was built in the mid-16th century, but already in the 18th century it was partially demolished. It no longer fulfilled defensive functions. In the 19th century, its remains were incorporated into the newly built tenement houses in its place. The photo shows Piwnica Gdańska – tenement house, which existed in its place, but was not rebuilt after the war. It was decided to rebuild the Barbican and gothic bricks were used for this, which is why it looks very real.

Nowe Miasto and Marie Curie House

Behind the city walls is Nowe Miasto. The name means New Town. New but not modern. It is also one of the oldest parts of Warsaw. It was founded at the beginning of the 15th century north of Old Warsaw.

The Old Town, as you can see, is not big. Already in the Middle Ages, people looking for work and a place to live came here, but the cramped Old Town tenement houses could not accommodate them. Gradually, houses for newcomers began to be built outside the walls. Among them were craftsmen, raftsmen and stallholders. Nowe Miasto was incorporated into the urban complex of Warsaw at the end of the 18th century.

During World War II, the New Town was also destroyed, although its reconstruction was not as spectacular and thorough as the reconstruction of the Old Town. This part is not on the UNESCO list. But it has its own charm. Some even prefer this part of the Old Town. It is less crowded, there are less souvenir shops while just as many cozy cafes and restaurants, as in the Old Town. It’s worth exploring the New Town, too.

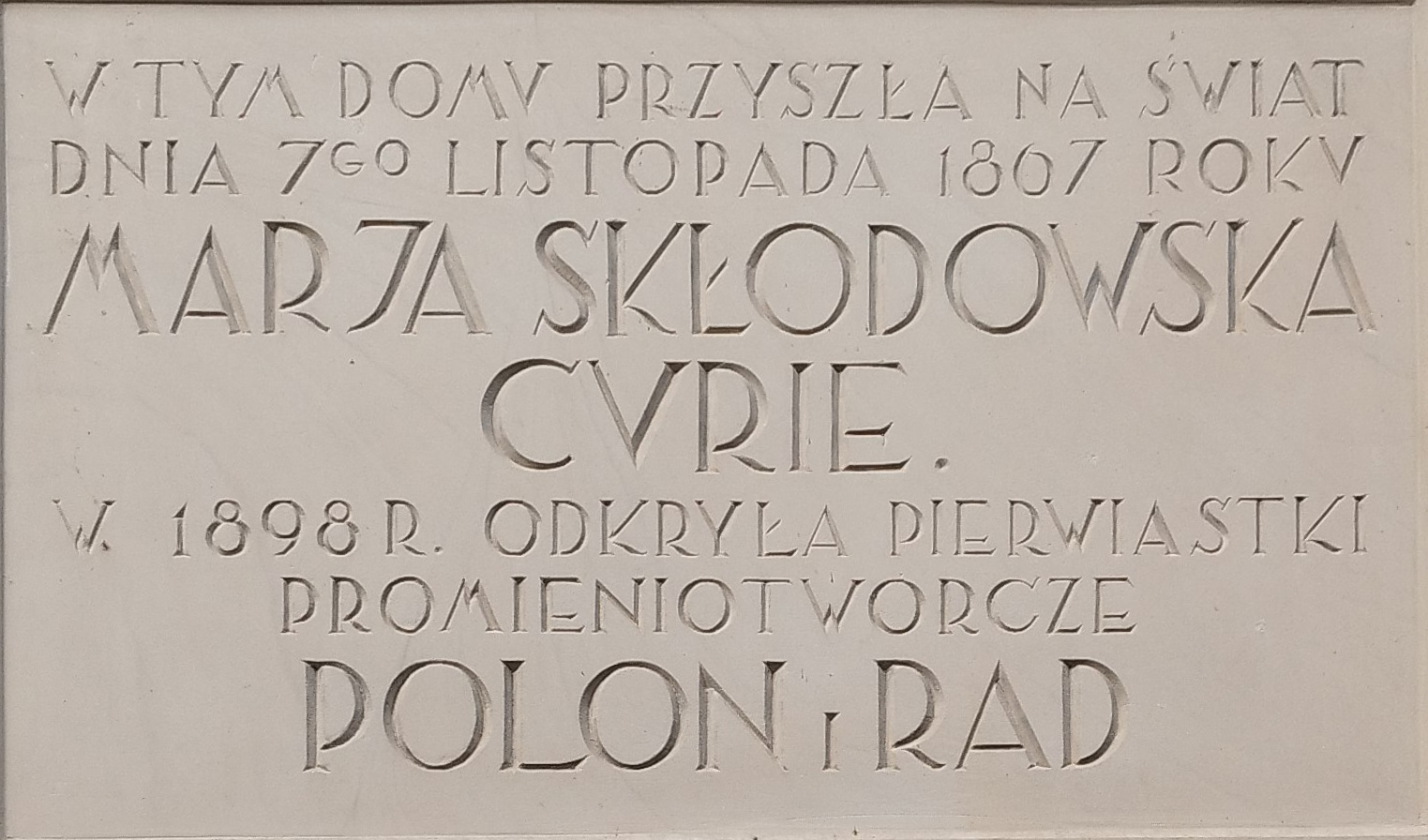

The building on Freta 16 can be considered an important piece of Polish history. It is the birthplace of the great scientist Maria Skłodowska-Curie. Yes, Madame Curie was Polish! And Varsovian! She was born here in 1867. Unfortunately, it was the time when Poland lost its independence, and this part of the country was under Russian occupation. As a woman, she could not study here, although she was extremely talented. She went to France where she made an amazing career. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, and eventually even two, in two different fields of science – physics and chemistry. She discovered two radioactive elements – radium and polonium. Polonium, as a symbol of her Polish identity. These chemical elements helped in modern cancer research. She is known by her French surname Curie. It was the name of her French husband, also a scientist, with whom she had worked together on radioactivity. During the First World War, she took x-rays of soldiers, driving special, adapted cars. For this purpose, she obtained a driving license as one of the first women. She was an example of a woman who was definitely ahead of her times.

Ghetto Wall Monument

At the intersection of Świętojerska and Nowiniarska Streets, look down at your feet. You will find a metal belt with the inscription “Ghetto Wall 1940-1943” in the pavement. Together with the plaques on the post standing next to it, it is a commemoration of the borders of Warsaw Ghetto. The ghetto it was the huge, walled district for Warsaw Jews. Nazis , occupiers of the city, made it and closed Jews there, isolating them from other citizens.

There are over 20 such commemorations in Warsaw, consisting of a metal plaque with a map of the ghetto and a strip indicating the course of the ghetto borders. They are located in the furthest border points of the former ghetto. It is a reminder of the dark period of city’s history.

The area of the city where the Jewish ghetto used to be is an example of a district that has never been rebuilt. Only monuments speak of the tragedy that happened there. Today there is a new residential district there. But this is a different story and a different example of how Warsaw came back to life after the war.

In our museum, the Museum of Warsaw, you will soon find a whole room dedicated to the history of the ghetto. Nowadays, you can admire the collection of Judaica, objects related to Jews, who majorly contributed to the history of our city and country.

Before the war, Warsaw was home to the largest Jewish community in Europe and the second largest one (after New York) in the world. At that time, Jews constituted 30% of the town’s population. Unfortunately, almost all of this community has practically disappeared as a result of the Holocaust.

The Nazis first closed the Jews in one place, in the area that isolated them from the rest of the city’s inhabitants that is why it was called the ghetto. It was surrounded by a wall. The strip in the pavement, near the place where you are standing, is a reminder of Ghetto’s wall. Some of the Jews squeezed in the ghetto died of exhaustion, starvation and overall inhumane living conditions. Most of them were transported to the gas chambers in the Treblinka extermination camp. The rest of them almost entirely perished during the ghetto uprising that broke out on April 19, 1943. After its fall, the area of the ghetto was razed to the ground. Therefore, you will not see the original Jewish houses here. They have never been rebuilt, but monuments commemorating this community have been unveiled in the area of the former Jewish ghetto.

It is impossible to miss a very big, green building nearby. It is the seat of the Supreme Court, as well as the Warsaw Court of Appeal.

Go to the back of this building to the last stop on the route of our tour. On the way to the Uprising Monument you will see the three statues of caryatids symbolizing the virtues: faith, hope and love.

Warsaw Uprising Monument

Next to the court building, there is a monument commemorating the Warsaw Uprising, unveiled in 1989. The Warsaw Uprising was the most tragic moment in the history of this city during World War II. During the Uprising over 150,000 people died. Most of the destruction of Warsaw is due to the two months of the uprising and the post-uprising period. The fight broke out August 1, and fell on October 2, 1944.

Even though the fight was fierce, unfortunately the Old Town fell on September 2. Some residents evacuated through the sewers, which is represented on the monument on the left.

The main part of the monument depicts the beginning of the fighting, a symbolic exit from the underground. You may be surprised that insurgents are not a regular, professional army. They are mostly young people, often casually dressed. They have armbands on their shoulders. This is not visible on the monument, but the armbands were in the colours of the Polish flag, white and red. Some of them wear soldiers’ helmets, some of them don’t. Sometimes they carry a rifle, sometimes a bottle of gasoline, sometimes nothing…

On the right side, on the wall, as well as on the tops of the columns behind the monument, you can see the symbol of Polish resistance, the so-called Kotwica which means “anchor”. P stands for Poland and W stands for fighting. It was painted on the walls and in other places as a symbol of the Poles’ struggle for independence.

In our headquarters, the Museum of Warsaw on the Main Old Town Square, you can find an unusual portrait of the foreigner, “Varsovian by choice”, who took part in that fight.

See more here: muzeumwarszawy.pl/portrait-of-august-agbola-obrown/

August-Agbola O’Brown was a jazz musician, born in Nigeria, who came to Warsaw from London in 1922. He played the drums in local jazz bands, settled down and started a family. As “Ali’ he was a participant of the Warsaw Uprising and fought in the south of the city centre. He survived the war, and emigrated with his family to London at the end of the 1950s. His history is situated on the margins of the Uprising’s mail narrative, anyway Warsaw Museum reclaims his story, as a part of the Warsaw’s mosaic.

We tried to show you what a phenomenon the reconstruction of the Old Town was. And, of course, we are extremly proud of this unimaginable effort and its miraculous results. But if it wasn’t for the war, the whole process wouldn’t be necessary.

The reconstruction of the Old Town can serve as an example of how to deal with such reconstructions. However, we wish no-one ever has to go through such experience. Nowhere in the world.